Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe the brain's reward system and the biological basis of addiction.

- Describe the genetic, epigenetic, and biological basis of individual variability with respect to opioids.

- Discuss psychological factors associated with opioid use and opioid use disorder.

- Explain how family and interpersonal factors influence the risk of substance use.

- Discuss how spiritual well-being can influence opioid use and opioid use disorder.

Key Concepts

- The effects of substances, including opioids, vary considerably from one person to the next.

- The brain’s reward system is built to make connections between behaviours and physiological outcomes. This system is geared to respond to short-term rewards: it can reinforce behaviours and actions that result in immediate positive outcomes, but over the long term it can reinforce behaviours and actions that lead to negative outcomes.

- Genetic variation can influence (increase or decrease) an individual’s experience with substance use and their risk of substance use disorder.

- Experiences including trauma can result in epigenetic changes that influence gene expression without changing the genetic sequence.

- Those experiencing chronic pain often have psychiatric comorbidities including depression, anxiety, and irritability. Data from specialty pain centers suggest that between 50 and 80 percent of individuals who experience chronic pain present with signs of psychopathology, making this the most prevalent comorbidity with chronic pain.

- Social and family environments can influence opioid use. Lack of social supports, family history of substance abuse, preadolescent sexual abuse, and childhood adversity are all known risk factors for developing opioid use disorder.

Before We Begin ...

Before we begin, please take a moment to brainstorm and write down five possible reasons that one person might have a different experience with a drug compared to another person. When you are ready, click to see if your answers are listed below.

- individual factors, including age, sex, physical size, muscle/fat composition, diet

- physiological factors, including circadian rhythms, seasonal variation, exercise, pregnancy, cardiovascular function, liver and kidney function

- other drugs, supplements, or foods, including prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, natural health products, food supplements, tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, opioids, or other recreational drugs

- disease states, including infections/fever, high blood pressure and other cardiovascular conditions, gastrointestinal conditions, endocrine (hormonal) conditions, immunological disease, mental health disorders, pain

- environmental factors, including occupational exposures, allergens, toxicants in the environment, in food, or in consumer products

- psychological factors, including stress levels, well-being, resiliency

- interpersonal and family factors, including family supports, intimate relationships

- social and structural factors, including access to health services, housing, employment

Did you think of anything missing from the list above?

The Brain's Reward System

The limbic system is a collection of areas in the brain that control or influence things like emotions, motivation, and memory.

Richfield, D. (2015). Mesolimbic Pathway. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mesolimbic_pathway.svg and licensed under (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Within the limbic system, the nucleus accumbens is a structure that is sometimes called the reward centre because it influences reward, reinforcement, and aversion. For example, different types of rewarding activities—drugs, sex, gambling, video games—all result in reward system activation. A common physiological response to these is the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Substances including nicotine, opioids, and others stimulate the reward centre. At the same time, the limbic system is consolidating memories. This makes you remember where you were, who you were with, and what you did when your reward system was activated. Activating the reward centre and forming these memories can influence your motivation to pursue similar rewards in the future.

NOTE: The biology happening within your limbic system is a key factor, but not the only factor, in determining whether a rewarding activity such as substance use will be a one-time experiment, an infrequent activity, or a regular activity, or might lead to addiction/substance use disorder.

We will now explore other factors related to the risk of substance use disorder.

Genetics, Opioids, and Substance Use Disorder

One risk factor for developing a substance use disorder is having a parent that experienced or was diagnosed with a substance use disorder.

The increased risk of parental history is due to several factors, including genetic inheritance (Wang et al., 2019).

The first studies (in the early 1960s) that identified a genetic component to addiction involved identical twins and alcohol use disorder. Similar findings were later found for opioid use disorder (Wang et al., 2019).

Genetic differences can occur within genes directly involved in:

- the opioid system (e.g., opioid receptors),

- the reward system (e.g., dopamine receptors or enzymes that metabolize dopamine), or

- in genes whose function we don't yet fully understand.

Genetic differences can also result in individual variation with respect to:

- reward and reinforcement,

- impulsivity and risk taking,

- responses to stress, and so on.

These factors might increase a person's risk of substance use disorder generally, including to opioids.

Epigenetics

Definition

- Epigenetic Variation

- Genetic variation involves differences in the DNA sequence for a particular gene. Epigenetic variation involves heritable changes in gene expression or phenotype that are not based on changes in the DNA sequence (Franco, 2019).

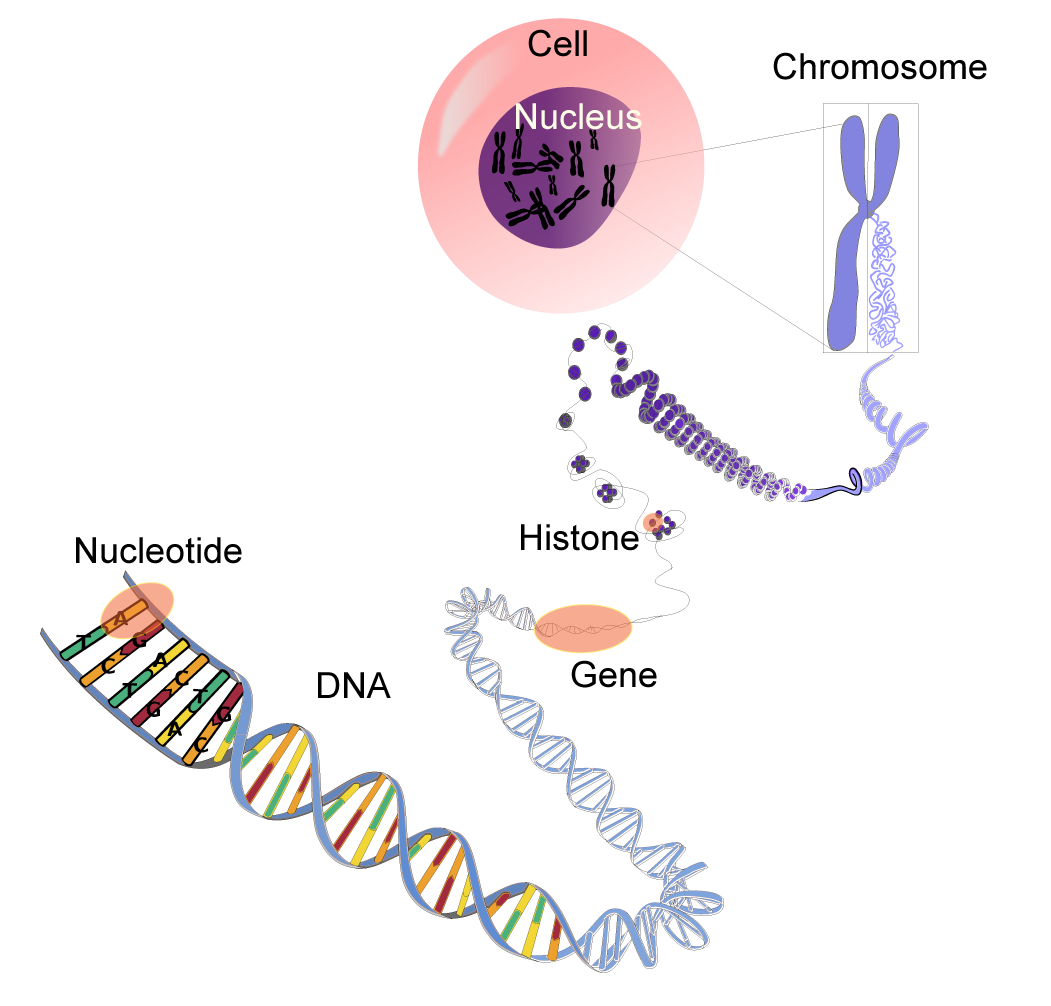

WaSu-Bio. (2017). DNA-terminology. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DNA-terminology.png and licensed under (CC0 1.0).

For a gene to be expressed into a protein, the portion of the chromosome that contains the gene must be accessible to the mechanisms of the cell that need to use it. Chemical changes to the proteins that DNA are wrapped around (called histones), can affect the expression of a gene. These changes can be something like the addition of acetyl groups or methyl groups. The effect can be long-lasting and can be passed from one generation to the next.

Epigenetic changes that affect opioid use and opioid use disorder in humans (and lab animals) can alter neurotransmitter function, change opioid receptor expression, and affect other key proteins in the brain.

- Epigenetics provides a mechanism for events in an individual's life (e.g., trauma) to alter their gene expression and predispose that person to substance use in the future.

- Epigenetic changes can even be passed from one generation to the next.

Psychological Factors that Influence Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder

Those experiencing chronic pain often have psychiatric comorbidities including depression, anxiety, irritability, and negative affect.

- Data from pain centers suggest that between 50 and 80 percent of individuals who experience chronic pain present with signs of psychopathology, suggesting a great comorbidity with chronic pain (Boersma & Linton, 2005; Celestin et al., 2009; Edwards et al., 2007).

- There is also mounting evidence that those with higher "pain catastrophizing" (a mental state characterized by feelings of helplessness and persistent beliefs, sometimes exaggerated, about pain and its effects) are more prone to misusing opioids.

- A prospective cohort study found that from a sample of 100 individuals with chronic pain, 90 percent were using opioid therapy, and 70 percent presented with a psychological problem such as depression, anxiety, and somatization (Manchikanti et al., 2004).

- Among patients with chronic pain, those with major psychopathology are also more likely to report great pain intensity, increased pain-related disability, higher levels of emotional distress associated with their pain, and poorer treatment outcomes than those without major psychopathology (Jamison & Mao, 2015).

- In another study, the effect of intravenous morphine was found to be greater in those who reported minor psychopathology than those with major psychopathology. Thus, those experiencing a greater negative effect might benefit less from opioid therapy (Jamison & Mao, 2015).

- There is also considerable overlap between affective disorders and substance use disorders. Opioid misuse was two to three times as likely in those experiencing a high-level negative effect (Becker et al., 2008).

Social and Familial Factors that Influence Opioid Misuse

Exposure to trauma, including early childhood and adolescent trauma, is associated with substance use and substance use disorder in adults (Garami et al., 2019). Stress related to childhood trauma can modulate brain development, including areas involved in:

- regulating emotional and behavioural stress responses,

- decision-making,

- reward behaviors, and

- impulsivity, including the prefrontal cortex (Garami et al., 2019).

"There may also be interactions between childhood trauma and a lack of parental or social support, maladaptive coping skills, and levels of daily stress that contribute to drug dependence and/or substance use later in life."

Traumatic events can induce chronic stress, for example, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and opioids can be used to escape/self-medicate distressing emotions and traumatic memories.

Social and family environments can encourage opioid use. Known risk factors for developing opioid use disorder include:

- lack of social supports,

- family history of substance use disorder,

- preadolescent sexual abuse, and

- childhood adversity.

Access to opioids in the home, including theft from family members or others, is a risk factor for opioid use disorder.

Spiritual Factors that Can Influence Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder

Urupong/iStock

Chronic pain can diminish spiritual well-being. Individuals reported that feeling drowsy on opioids resulted in withdrawal from spiritual obligations. This might create a negative downward cycle in which diminished spiritual well-being increases feelings of chronic pain and dependence on opioids.

On the other hand, those who were able to manage their chronic pain with opioids reported fulfilment of spiritual obligations.

- Spiritual distress is experienced in 25 percent of people receiving cancer treatment (Schultz et al., 2017).

- The spiritual dimension of health has recently been recognized as an important aspect that might influence abstention, substance use, and relapse (Edlund et al., 2010).

Unlike other diseases that are more biological, substance use is strongly influenced by psychological and social factors, which explains why spirituality may also influence substance use.

- Among a sample of 312 individuals recovering from opioid use disorder, those with significantly lower scores on a spiritual well-being scale were more likely to relapse than those with higher scores (Noormohammadi et al., 2017).

- Some preliminary studies show that meditation might have positive effects on mental health and serve as a protective factor against substance use disorder (Priddy et al., 2018).

- A randomized controlled trial also found that mindfulness-oriented recovery enhanced analgesic effects and reduced cravings for opioid use (Garland et al., 2019).

Environmental Factors Influencing Opioid Misuse

Sociodemographic factors are associated with the type of opioid used in opioid-related overdose.

Age and gender: younger men (average age 38) were more likely to be involved in a fentanyl-related death (Belzak & Halverson, 2018).

Community population: smaller Canadian communities have experienced double the opioid poisoning hospitalization rates as the larger cities. Brantford, a small town in Ontario, reported 3.5 times the Ontario average for hospitalization for opioid poisoning (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018). This might be due to a higher percentage of older adults living in rural areas with:

- greater access to these drugs,

- normalization of drug use in these communities, and

- more efficient circulation of diverted opioids in close social networks that are rarer in urban settings.

This is concerning because of the undersupply of mental health services and addictions treatment services in rural versus more urbanized centres.

Income: in Alberta and Ontario, the majority of opioid-related deaths occurred in lower- to middle-income neighbourhoods, although neighbourhoods across all socioeconomic groups have been impacted by opioids (Belzak & Halverson, 2018).

- In Ontario, harms related to opioid-use in 2016 were highest in the lowest-income quintile, including emergency department visits, opioid poisoning, and neonatal abstinence syndrome.

- The lowest-income quintile had at least double the rates of opioid-related harms of the highest-income quintile.

- This suggests that income inequality can be a root cause of health disparities in opioid-related illness.

Indigenous Peoples (including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) have been heavily impacted by opioid-related harm and disproportionately affected by substance use.

- First Nations people were five times as likely as their non–First Nations counterparts to experience an opioid-related overdose event and three times as likely to die from an opioid-related overdose (Belzak & Halverson, 2018).

- Indigenous communities that are more remote and rural are struggling less with opioid problems than those closer to urban centres.

The disparity of opioid use problems seen in these communities is understood to be rooted in a history of colonization and racism causing trauma, loss, poverty, and family separation, which had seismic and multi‐generational impacts on the mental well-being of Indigenous People.

Questions

References

Becker, W. C., Sullivan, L. E., Tetrault, J. M., Desai, R. A., & Fiellin, D. A. (2008). Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among US adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 94(1–3), 38–47.

Belzak, L., & Halverson, J. (2018). Evidence synthesis—The opioid crisis in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 38(6), 224.

Boersma, K. & Linton, S.J. (2005). Screening to identify patients at risk: profiles of psychological risk factors for early intervention. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 21(1), 38-43.

Browne, C. J., Godino, A., Salery, M., & Nestler, E. J. (2020). Epigenetic mechanisms of opioid addiction. Biological Psychiatry, 87(1), 22–33.

Brunton, L. L., Hilal-Dandan, R., & Knollmann, B. C. (2018). Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). Opioid-related harms in Canada.

Celestin, J., Edwards, R. R., & Jamison, R. N. (2009). Pretreatment psychosocial variables as predictors of outcomes following lumbar surgery and spinal cord simulation: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Pain Medicine, 10(4), 639-653.

Dersh, J., Gatchel, R. J., Polatin, P., & Mayer, T. (2002). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic work-related musculoskeletal pain disability. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 44(5), 459–446.

Edlund, M. J., Martin, C., Devries, A., Fan, M., Brennan Braden, J., & Sullivan, M. (2010). Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clinical Journal of Pain, 26(1), 1-8.

Edwards, R. R., Smith, M. T., Klick, B., Magyar-Russell, G., Haythornthwaite, J. A., Holavanahalli, R… & Fauerbach, J. A. (2007). Symptoms of depression and anxiety as unique predictors of pain-related outcomes following burn injury. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 34(3), 313-322.

First Nations Health Authority. (2017). Overdose data and First Nations in BC: Preliminary findings. http://www.fnha.ca/newsContent/Documents /FNHA_OverdoseDataAndFirstNations InBC_PreliminaryFindings_FinalWeb .pdf

Franco F. (2018). Childhood abuse, complex trauma and epigenetics. PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/lib/childhood-abuse-complex-trauma-and-epigenetics/

Garami, J., Valikhani, A., Parkes, D., Haber, P., Mahlberg, J., Misiak, B., Frydecka, D., & Moustafa, A. A. (2019). Examining perceived stress, childhood trauma and interpersonal trauma in individuals with drug addiction. Psychological Reports, 122(2), 433–450.

Garland, E. L., Atchley, R. M., Hanley, A. W., Zubieta, J. K., & Froeliger, B. (2019). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement remediates hedonic dysregulation in opioid users: Neural and affective evidence of target engagement. Science Advances, 5(10), eaax1569.

Grattan, A., Sullivan, M. D., Saunders, K. W., Campbell, C. I., & Von Korff, M. R. (2012). Depression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic opioid therapy recipients with no history of substance abuse. The Annals of Family Medicine, 10(4), 304–311.

Hah, J. M., Sturgeon, J. A., Zocca, J., Sharifzadeh, Y., & Mackey, S. C. (2017). Factors associated with prescription opioid misuse in a cross-sectional cohort of patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 979.

Hasin, D., Liu, X., Nunes, E., McCloud, S., Samet, S., & Endicott, J. (2002). Effects of major depression on remission and relapse of substance dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(4), 375–380.

Jamison, R. N., & Mao, J. (2015). Opioid analgesics. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(7), 957–968. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(15)00342-0/fulltext

Katzung, B. G. (2018). Basic and clinical pharmacology (14th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Lutz, J., Gross, R., Long, D., & Cox, S. (2017). Predicting risk for opioid misuse in chronic pain with a single-item measure of catastrophic thinking. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 30(6), 828–831.

Manchikanti, L., Damron, K. S., McManus, C. D., & Barnhill, R. C. (2004). Patterns of illicit drug use and opioid abuse in patients with chronic pain at initial evaluation: A prospective, observational study. Pain Physician, 7(4), 431–437.

Michalak, L., Trocki, K., & Bond, J. (2007). Religion and alcohol in the US National Alcohol Survey: How important is religion for abstention and drinking? Drug and alcohol dependence, 87(2–3), 268–280.

Noormohammadi, M. R., Nikfarjam, M., Deris, F., & Parvin, N. (2017). Spiritual well-being and associated factors with relapse in opioid addicts. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 11(3), VC07.

Priddy, S. E., Howard, M. O., Hanley, A. W., Riquino, M. R., Friberg-Felsted, K., & Garland, E. L. (2018). Mindfulness meditation in the treatment of substance use disorders and preventing future relapse: Neurocognitive mechanisms and clinical implications. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 9, 103.

Salehian, S. (2018). Is spirituality effective in addiction recovery and prevention? The Journal of Baha'i Studies, 28(4), 69–90.

Schultz, M., Meged-Book, T., Mashiach, T., & Bar-Sela, G. (2017). Distinguishing between spiritual distress, general distress, spiritual well-being, and spiritual pain among cancer patients during oncology treatment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(1), 66–73.

Setnik, B., Roland, C. L., Goli, V., Pixton, G. C., Levy-Cooperman, N., Smith, I., & Webster, L. (2015). Self-reports of prescription opioid abuse and diversion among recreational opioid users in a Canadian and a United States city. Journal of Opioid Management, 11(6), 463–473.

Wang, S.-C., Chen, Y.-C., Lee, C.-H., & Cheng, C.-M. (2019). Opioid addiction, genetic susceptibility, and medical treatments: A review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20, 4294.

Wasan, A. D., Kaptchuk, T. J., Davar, G., & Jamison, R. N. (2006). The association between psychopathology and placebo analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain. Pain Medicine, 7(3), 217–228.

Webster, L. R. (2017). Risk factors for opioid-use disorder and overdose. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 125(5), 1741–1748.