Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- List the factors that place individuals at risk of opioid overdose.

- Describe how these risk factors can lead to an opioid overdose.

- Match effective risk reduction interventions to risk factors.

- Explain how such interventions mitigate the risk of opioid overdose.

Key Concepts

- Injected opioid use is more likely to cause an overdose, so clients need to avoid or reduce injection drug use.

- When possible, clients should limit total daily opioid use to 90 morphine equivalents per day or less.

- It is important to use lower potency opioid if possible because, whether prescribed or unregulated, the higher the potency the greater the risk for overdose.

- Changing an opioid use can increase the risk of a medication error, especially in the presence of other drugs.

- Clients should avoid combining opioids with other central nervous system (CNS) depressants, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines should be avoided.

- An individual who previously used opioids, but has experienced a period of opioid abstinence for any reason, is at increased risk of overdose if they begin to use opioids again at doses they were using previously.

- Unregulated opioids can vary with respect to the amount and type of opioid. Opioids have also been found in other unregulated drugs.

- People using opioids alone, particularly injection opioids, have an increased risk that an overdose will be fatal.

- In an overdose, the presence of another person and a naloxone kit reduces the risks that an overdose will be fatal.

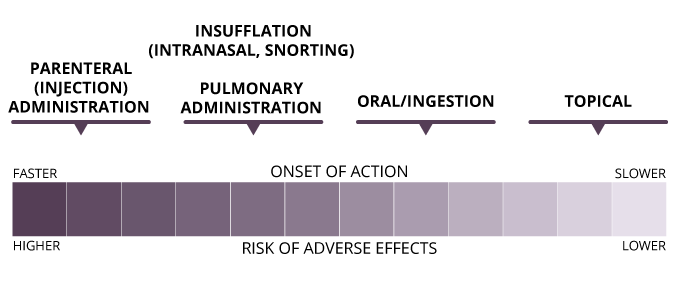

Dose and Route of Administration

Although there is variability between individuals, and tolerance can influence opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD), it is dose-dependent: the greater the dose, the greater the risk of overdose.

There are several routes of administration for opioids:

- epidural injection

- insufflation/intranasal

- intramuscular injection

- intravenous injection

- oral

- pulmonary

- rectal

- subcutaneous injection

- sublingual/buccal

- topical

Adverse effects, including OIRD, can occur more frequently for routes of administration that result in a fast onset of action.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Potency

The potency of a drug describes how much of the drug is required for a particular effect. As an example, three drugs with very different potencies are used to relieve migraine headache. All work quite well, but the doses administered to achieve this effect are:

- 0.5 mg of Drug A

- 25 mg of Drug B

- 1500 mg of Drug C

Drug A is the most potent one of these three because it required the smallest dose to achieve an effect.

Opioid potency is often described as relative potency, as it is described relative to the original opioid, morphine. Often, these values are listed as the morphine milligram equivalent (MME).

OIRD can occur with ~200 mg of morphine (in someone without any opioid tolerance), so it could occur with only a few milligrams of fentanyl, and tens of micrograms of high-potency fentanyl, such as carfentanil.

Hydromorphone

The MME (or relative potency) for hydromorphone is 4. Thus, a dose of 1 mg of hydromorphone is equivalent to 4 mg of morphine.

Fentanyl (injected)

The MME for fentanyl (injected) is 50–100. Thus, a dose of 1 mg of fentanyl is equivalent to 50–100 mg of morphine.

Carfentanil

The MME for carfentanil is close to 10,000. Carfentanil is not approved for use in humans in any capacity; it is used to sedate large animals. A dose of 1mg of carfentanil is equivalent to 10,000 mg of morphine, which is well beyond a fatal dose.

Changes in Opioid Use

When changing a medical opioid regimen, there is a small chance of medication error or the patient misunderstanding the new regimen. Prescribers, pharmacists, other health and service professionals, and patients need to be vigilant to ensure the following:

- When switching opioids, the morphine equivalent daily dose has been calculated correctly.

- When switching doses, the new dose and regimen are appropriate.

- When switching products or dosage forms, the new dose and regimen are appropriate.

- The patient understands the reason for the change, the new product, dose, and/or dosing regimen.

When changing an unregulated opioid or where a client is obtaining an unregulated opioid, there is a risk of

- the new product being more concentrated than the previous product

- the new product containing a different opioid than the previous product

- the new product containing additional drugs, including additional opioids or other CNS depressants

Users, overdose prevention sites, and supervised consumption sites are employing several analytical techniques to test user-provided samples for the presence of fentanyl or other opioids. These may include advanced chemical analysis with research equipment or fentanyl test strips.

Opioids and Other CNS Depressants

Opioids are not the only type of drug that can cause respiratory depression. Other CNS depressants, including alcohol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates can also cause respiratory depression.

When taken together, CNS depressants can cause additive or synergistic effects.

Additive Effects

In pharmacology, additive effects refer to two or more drugs that have the same effect on the body.

Example: Stimulant A increases blood pressure by 10 points and Stimulant B increases blood pressure by 10 points. Stimulant A and B, taken together, increase blood pressure by 20 points (simply add the two effects).

Synergistic Effects

Example: Stimulant C and D each increase blood pressure by 10 points when used alone. When taken together, C and D result in an increase of 40 points. The effects of the two drugs together are greater than the sum of each drug used alone.

When opioids are used in combination with CNS depressants, a smaller dose of opioid is needed to cause respiratory depression.

Case Study

A friend of yours who uses opioids, usually via injection, purchases an unregulated opioid from a new source. He uses the drug and decides to lie down in another room. You check on him and find that he is unresponsive. His lips are slightly blue, he is breathing but very shallowly, and he does not respond to shouting or shaking. His pupils are small. You suspect an opioid overdose and get your naloxone kit. You haven’t administered naloxone before but were a bystander at another overdose a month ago. You administer one dose of nasal naloxone. You shout once more but there is no response, his breathing is still very shallow. You call 911. After three minutes, you administer another naloxone dose, again without effect. When paramedics arrive, additional doses of naloxone are given, but the person is taken to hospital without showing any apparent response.

Instructions

Read the case study example above carefully. Consider your answer to each question below, then click on the ‘feedback’ button to reveal the authors’ response.

Questions

1. Naloxone didn’t seem to work. Could this have been a benzodiazepine overdose?

Authors' Response

Many of the symptoms of CNS depressant overdose are similar (heavy sedation, nonresponsive, shallow breathing, etc.). However, the pinpoint pupils point to opioids being present. The opioid was from a new source, so it could have been a more potent fentanyl analogue, or the product could have contained a higher dose of an opioid that required more naloxone than usual. Or it could have been a combination of opioid and benzodiazepine such as etizolam.

2. Was this a case of a naloxone-resistant opioid?

Authors' Response

No. All known unregulated opioids have effects that are reversible by naloxone. In a combination opioid-benzodiazepine overdose, naloxone should still be administered and would still be effective, but only in reversing the effects of the opioid. The effects of the benzodiazepine would not be reversed, so the person might still be heavily sedated.

3. Should people even bother administering naloxone for a mixed overdose?

Authors' Response

YES! The naloxone administered in this case would have reversed the opioid component of the respiratory depression and may have saved the victim. Additional interventions can then be carried out in the emergency room (flumazenil is a benzodiazepine antagonist that can be administered). Even if this case had just been a benzodiazepine overdose, naloxone would not have caused further harm.

Loss of Tolerance

Like all systems in the body, the opioid system is constantly fine-tuned. If the system becomes over-activated, the body takes steps to reduce this activity, and if the system is downregulated, the body takes steps to increase activity.

Definition

- Exogenous Opioids

- Opioids from an external source rather than those the body produces itself.

- Endogenous Opioids

- Naturally occurring neuromodulators, produced and secreted by nerve cells.

When exogenous opioids are taken, the endogenous opioid system detects the over-activity they cause, and reacts by reducing activity. It does this by reducing production of endogenous opioid peptides and reducing the number of opioid receptors, among other things.

- At this stage, the body has begun to adapt to the presence of the exogenous opioid.

- As the body adapts, tolerance can occur: the person needs more and more of the drug to produce the same effect.

If opioid use is stopped, the opioid system returns back to its original state.

NOTE: Loss of tolerance can occur more quickly than the development of tolerance. Therefore, opioid users who have experienced a period of abstinence or markedly reduced doses for any reason (e.g., voluntary abstention/cutting down, residential treatment or other treatment programs, incarceration, hospitalization) are at risk of experiencing an overdose if they return to opioid use at doses they used in the past.

Unregulated Opioids

Unregulated opioids are produced outside of the pharmaceutical regulatory system. They are also referred to as illegal, illicit, black market, or bootleg.

In addition to unregulated opioids, regulated prescription opioids can be diverted for illegal sale after illegal importation, theft (e.g., from a pharmacy, home, or individual), or being obtained via prescription but sold to others instead.

Several unregulated synthetic opioids have been identified in North America. For example, fentanyl and its analogues including 3-methylfentanyl, carfentanil, beta-hydroxyfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, and many others.

Trends in the Unregulated Opioid Market

The increase in the number of cases of OIRD/overdose and opioid-related mortality has coincided with changes in the illicit opioid use market, from diverted prescription opioids, particularly OxyContin, to heroin, to unregulated synthetic fentanyls.

- OxyContin is a pharmaceutical-grade opioid, that is, each pill contained a known amount of oxycodone and each pill contained the same amount.

- Fentanyls are synthesized outside the regulated system, with no quality control.

- Fentanyls are generally more potent than pharmaceutical opioids, so small mistakes made in the supply chain, or by the user, can disproportionally increase the risk of overdose.

NOTE: Fentanyl is 50–100 times as potent as morphine.

NOTE: Fentanyl analogues are molecular copies of fentanyl with minor chemical modifications. Fentanyl analogues may be less potent, equipotent, or more potent than fentanyl itself (e.g., carfentanil is 50–100 times as potent as fentanyl).

Unregulated drugs may contain one or more fentanyl/analogues, and opioids may be found in other types of drugs, including cocaine.

Naloxone

- Naloxone is an opioid receptor antagonist, i.e. blocker

- Naloxone competes with opioids (agonists) for binding to opioid receptors, including µ opioid receptors in the respiratory centre

- In OIRD, naloxone reverses the effects of the opioid at the respiratory centre, restoring normal physiological function/breathing

- Naloxone also reverses other effects of opioids, including the effects of opioids on pain and euphoria, and administration can also result in shivering, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea

- In opioid-dependent individuals, naloxone may precipitate withdrawal symptoms.

Fvasconcellos. (2008). Naloxone [Image]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Naloxone.svg.

Naloxone Infographic (PDF)

University of Waterloo - Faculty of Science, School of Pharmacy. Naloxone. (2016). Reproduced with permission of University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy ©Pharmacy5in5.com Retrieved online from: https://uwaterloo.ca/pharmacy/sites/ca.pharmacy/files/uploads/files/naloxone_infographic_accessible.pdf

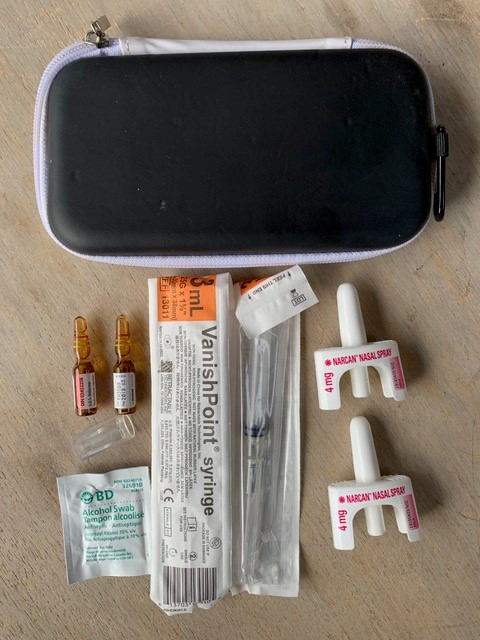

Naloxone Kits

© Michael Beazely

Naloxone kits typically include:

- A hard case

- Two or more doses of naloxone

- Narcan® Nasal Spray (4 mg nalaoxone /0.1 mL) OR

- 1 mL ampoules or vials of naloxone hydrochloride 0.4 mg/mL intramuscular injection

- Rescue breathing barrier

- Pair of non-latex gloves

- Training card and/or instructional insert

- Alcohol swaps (for injectable naloxone)

- Two safety syringes, 25g, 1 inch needle (for injectable naloxone)

- Ampoule opening device (for injectable naloxone)

Depending on the jurisdiction, naloxone kits can be obtained (free of charge, often without a health card) from pharmacies, public health units, overdose prevention sites and other outreach services.

If a pharmacy doesn’t advertise, offer, or stock naloxone—ASK! One reason that pharmacies may not stock naloxone kits is that they don’t believe their patients and customers are interested in obtaining a kit.

Naloxone Administration

- Intramuscular (IM) naloxone can be injected into a large muscle (shoulder, leg)

- Intranasal naloxone (IN) is sprayed into a nostril

- If there is no effect (no change in breathing, responsiveness) a second dose or additional doses may be administered

- It is not possible to give too much naloxone.

- When an overdose is suspected but not certain, naloxone should be given anyway.

- 9-1-1 should always be called, even if the overdose is successfully reversed with naloxone. The effects of naloxone can wear off more quickly than the effects of many opioids.

How to Administer Intranasal Naloxone:

How to Administer Intramuscular Naloxone:

Questions

Match the Intervention(s) from the list below to the Risk Factor for opioid overdose.

- When restarting prescription opioid therapy or opioid agonist therapy, or when returning to unregulated opioid use, start with doses that are lower than those used previously, and take care when increasing opioid doses.

- Use lower potency opioids and take steps (don’t use alone, have a naloxone kit) to reduce the risk of overdose.

- Wherever possible, limit total daily opioid doses to 90 morphine equivalents per day, or less.

- Avoid or reduce injection drug use.

| Risk factor for opioid overdose | Intervention(s) to reduce the risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Using higher potency opioids. Whether prescription or unregulated, the higher the potency of the opioid, the higher the overdose risk. |

|

|

| Route of administration. Injected opioid use is more likely to cause an overdose compared to ingested opioids. |

|

|

| Loss of tolerance. If an individual that previously used opioids but has experienced a period of opioid abstinence for any reason, they are at an increased risk of overdose if they begin to use opioids again at doses they were using previously. |

|

|

| Using higher daily doses of prescription opioids (greater than 90 morphine equivalents per day). |

|

|

Correct! The following matches are correct:

| Risk factor for opioid overdose | Intervention(s) to reduce the risk |

|---|---|

| Using higher potency opioids. Whether prescription or unregulated, the higher the potency of the opioid, the higher the overdose risk. | B - Use lower potency opioids and take steps (don’t use alone, have a naloxone kit) to reduce the risk of overdose. |

| Route of administration. Injected opioid use is more likely to cause an overdose compared to ingested opioids. | D - Avoid or reduce injection drug use. |

| Loss of tolerance. If an individual that previously used opioids but has experienced a period of opioid abstinence for any reason, they are at an increased risk of overdose if they begin to use opioids again at doses they were using previously. | A - When restarting prescription opioid therapy or opioid agonist therapy, or when returning to unregulated opioid use, start with doses that are lower than those used previously, and take care when increasing opioid doses. |

| Using higher daily doses of prescription opioids (greater than 90 morphine equivalents per day). | C - Wherever possible, limit total daily opioid doses to 90 morphine equivalents per day, or less. |

Incorrect. The following matches are correct:

| Risk factor for opioid overdose | Intervention(s) to reduce the risk |

|---|---|

| Using higher potency opioids. Whether prescription or unregulated, the higher the potency of the opioid, the higher the overdose risk. | B - Use lower potency opioids and take steps (don’t use alone, have a naloxone kit) to reduce the risk of overdose. |

| Route of administration. Injected opioid use is more likely to cause an overdose compared to ingested opioids. | D - Avoid or reduce injection drug use. |

| Loss of tolerance. If an individual that previously used opioids but has experienced a period of opioid abstinence for any reason, they are at an increased risk of overdose if they begin to use opioids again at doses they were using previously. | A - When restarting prescription opioid therapy or opioid agonist therapy, or when returning to unregulated opioid use, start with doses that are lower than those used previously, and take care when increasing opioid doses. |

| Using higher daily doses of prescription opioids (greater than 90 morphine equivalents per day). | C - Wherever possible, limit total daily opioid doses to 90 morphine equivalents per day, or less. |

Match the Intervention(s) from the list below to the Risk Factor for opioid overdose.

- Avoid mixing opioids and other CNS depressants. If two CNS depressants are used, speak to a health and social service professional and/or reduce the doses of one or both.

- Avoid using opioids, particularly injection opioids, alone.

- Avoid using unregulated opioids. If unregulated opioids are used, avoid injecting, use test doses, don’t use alone, and have a naloxone kit.

- When changing your opioid prescription, dose, double-check with your pharmacists that the dose and regimen are appropriate, and that you understand the new directions. Have a naloxone kit if you are changing your unregulated opioid source.

| Risk factor for opioid overdose | Intervention(s) to reduce the risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Using unregulated opioids. Unregulated opioids can vary with respect to the amount and type of opioid. Much of the unregulated drug supply in Canada is fentanyl or its analogues. |

|

|

| Combining opioids with other CNS depressants, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines. |

|

|

| Using alone. In an overdose, another person needs to be there to call 911/administer naloxone. |

|

|

| Changing opioid use. This can increase the risk of a medication error or taking the wrong dose. For unregulated opioids, switching the source of the drug may result in exposure to a different opioid, different dose, or the presence of other drugs. |

|

|

Correct! The following matches are correct:

| Risk factor for opioid overdose | Intervention(s) to reduce the risk |

|---|---|

| Using unregulated opioids. Unregulated opioids can vary with respect to the amount and type of opioid. Much of the unregulated drug supply in Canada is fentanyl or its analogues. | G - Avoid using unregulated opioids. If unregulated opioids are used, avoid injecting, use test doses, don’t use alone, and have a naloxone kit. |

| Combining opioids with other CNS depressants, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines. | E - Avoid mixing opioids and other CNS depressants. If two CNS depressants are used, speak to a health and social service professional and/or reduce the doses of one or both. |

| Using alone. In an overdose, another person needs to be there to call 911/administer naloxone. | F - Avoid using opioids, particularly injection opioids, alone. |

| Changing opioid use. This can increase the risk of a medication error or taking the wrong dose. For unregulated opioids, switching the source of the drug may result in exposure to a different opioid, different dose, or the presence of other drugs. | H - When changing your opioid prescription, dose, double-check with your pharmacists that the dose and regimen are appropriate, and that you understand the new directions. Have a naloxone kit if you are changing your unregulated opioid source. |

Incorrect. The following matches are correct:

| Risk factor for opioid overdose | Intervention(s) to reduce the risk |

|---|---|

| Using unregulated opioids. Unregulated opioids can vary with respect to the amount and type of opioid. Much of the unregulated drug supply in Canada is fentanyl or its analogues. | G - Avoid using unregulated opioids. If unregulated opioids are used, avoid injecting, use test doses, don’t use alone, and have a naloxone kit. |

| Combining opioids with other CNS depressants, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines. | E - Avoid mixing opioids and other CNS depressants. If two CNS depressants are used, speak to a health and social service professional and/or reduce the doses of one or both. |

| Using alone. In an overdose, another person needs to be there to call 911/administer naloxone. | F - Avoid using opioids, particularly injection opioids, alone. |

| Changing opioid use. This can increase the risk of a medication error or taking the wrong dose. For unregulated opioids, switching the source of the drug may result in exposure to a different opioid, different dose, or the presence of other drugs. | H - When changing your opioid prescription, dose, double-check with your pharmacists that the dose and regimen are appropriate, and that you understand the new directions. Have a naloxone kit if you are changing your unregulated opioid source. |

References

Harm Reduction Services Team. (2019). Etizolam: Public notice. Alberta Health Services. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hrs/if-hrs-etizolam-public-notice.pdf

Armenian, P., Whitman, J. D., Badea, A., Johnson, W., Drake, C., Dhillon, S. S., Rivera, M., Brandehoff, N., & Lynch, K. L. (2019). Unintentional fentanyl overdoses among persons who thought they were snorting cocaine—Fresno, California, January 7, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68, 687–688.

Boom, M., Niesters, M., Sarton, E., Aarts, L., Smith, T. W., & Dahan, A. (2012). Non-analgesic effects of opioids: Opioid-induced respiratory depression. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 18, 5994–6004.

Brunton, L. L., Hilal-Dandan, R., & Knollmann, B. C. (2018). Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (13 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Katzung, B. G. (2018). Basic and clinical pharmacology (14 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Solimini, R., Pichini, S., Pacifici, R., Busardo, F. P., & Giorgetti, R. (2018). Pharmacotoxicology of non-fentanyl derived new synthetic opioids. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, 654.