Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Identify the components of an assessment of a person using opioids.

- Describe the concepts underlying person-/client-centred care.

- Describe the family life cycle stages and how each is impacted uniquely by a family member’s substance use.

- Describe the principles guiding whole family care in opioid use.

- Describe how community needs related to opioid use may be assessed.

Key Concepts

- Assessing and responding to an individual’s unique needs related to opioid use is enhanced by a person-centred approach.

- A collaborative assessment approach involving the individual and family is recommended.

- Individual response is different based upon which family life cycle stage the substance use is occurring in, and needs/responses will change as families progress through the stages.

- Assessment needs to be inclusive and holistic.

- Intersectoral approaches are often required to assess and respond to the needs of communities during an opioid crisis.

Principles of Person-centred Care

Person-centred care, a term sometimes used interchangeably with client-centred care, means tailoring services, including assessment and intervention, to the unique needs of the individual.

- The person and their self-defined goals and values are included in the assessment and intervention planning process.

- Person-centred care is characterized by the appreciation of each client as a unique human being, identifying strengths and challenges with a focus on building resilience.

- Person-centred care emphasizes

- collaborative decision-making,

- active listening,

- respect for the client’s preferences, and

- transparent and clear communication within a framework of respect.

- The person’s own treatment goals are considered and revisited regularly to ensure they are still applicable as an individual’s circumstances may change over time.

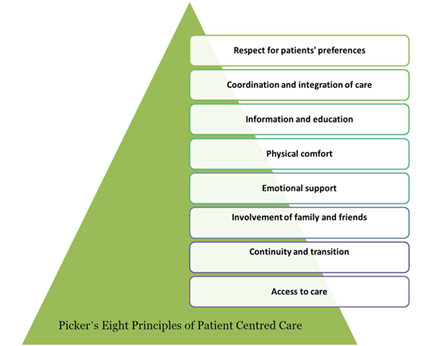

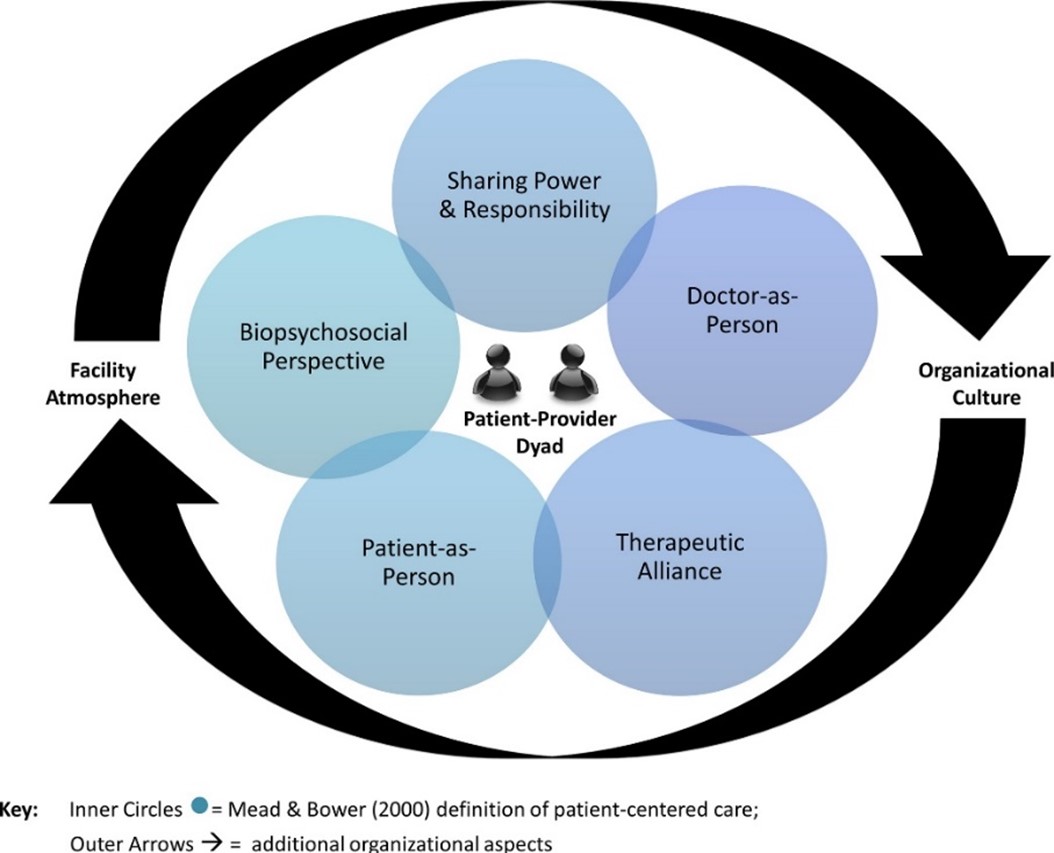

Several models exist that describe person-centered care. Two of which are shown below.

Eight Principles of Patient Centred Care

The eight principles exist in a pyramid. From the base of the pyramid, they are: 1. Access to care, 2. Continuity and transition, 3. Involvement of family and friends, 4. Emotional support, 5. Physical comfort, 6. Information and education, 7. Coordination and integration of care, and 7. Respect for patients’ preferences.

(Picker, 1993). Used with permission from the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care: www.ipfcc.org.

Mead and Bower’s (2000) conceptual framework for client-centred care describes five conceptual dimensions that support the provision of person-centered care.

Client-centredness: A Conceptual Framework

(Mead & Bower, 2000)

The five components of Mead and Bower’s (2000) model are as follows:

- A biopsychosocial perspective (i.e., understanding clients’ illnesses within a broader biopsychosocial framework)

- The client-as-person (i.e., understanding the individual’s experience of illness)

- The sharing of power and responsibility (including making shared decisions)

- The therapeutic alliance (i.e., emphasizing the importance of the provider–patient relationship, joint agreement over goals of treatment, and the client’s perception of the provider as caring and sympathetic)

- The doctor-as-person (i.e., attention to the influence of the personal qualities of the doctor, as well as a self-awareness of emotional responses and position of power and privilege)*

*Since Mead and Bower’s article was written, the term provider has expanded to include others who are health and social service providers, such as nurses, pharmacists, social workers, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, among others.

The Importance of Assessment

Assessment is an important first step in all scenarios of opioid use to provide context, and to better understand the person using drugs. Assessment also provides the basis on which to plan the intervention/treatment.

Considerations Before an Assessment

- The health and social service provider needs to complete the assessment within a broader understanding of opioid use disorder.

- Identifying problem areas is one component of the assessment; however, strengths and resilience should also be included.

- When conducting an assessment, the health and social service provider should ensure the physical setting creates a welcoming environment that is safe.

- a respectful environment must be considered when conducting remote/virtual assessments as well.

- The setting should also provide adequate privacy to the individual and be free of distractions (noise in a hallway, an open door, a lack of comfortable seating, or unnecessary interruptions such as cell phones).

- A welcoming environment can help people feel safe disclosing facts they may find embarrassing or worry they will be judged for.

- The demeanour of the health and social service provider is important to conveying acceptance. A warm and open manner should be used, with attention given to the pacing of questions and to providing adequate time to avoid rushing or implying a sense of urgency.

Components of an Assessment for Opioid Use

An assessment can involve several components, including mental health history, substance use history, substance use disorder treatment history, social history, family history, and medical history as well as coping abilities, resilience, and strengths.

Mental Health History

(SAMHSA, 2007)

Assessing for comorbid mental health issues is critical because issues in mental health are prevalent among people with substance use disorder. The presence of a mental health issue can complicate treatment and impact the prognosis and recovery.

For example, substance use disorders can mimic or induce depression and anxiety disorders.

- In one study, nearly 20 percent of primary care clients with opioid addiction had major depression.

Although substance-induced depression and anxiety disorders may improve with abstinence, they may still require treatment.

- Taking a thorough history of the relationship between an individual’s psychiatric symptoms and periods of substance use and abstinence is advised for careful planning of management or treatment options.

Substance Use History

(SAMHSA, 2007)

Substance use histories can help gauge the degree to which the opioid is used, inform treatment planning, identify contraindications, and capture the narrative of the impact the opioid use has had on the person’s life and relationships.

- Substance use assessment focuses on the severity of a person’s substance use by exploring historical features of their use, including the age and context at first use, the route of ingestion (e.g., injection), and the tolerance history, including issues related to withdrawal, drug mixing, and overdose.

- History taking should also explore the current patterns of use to inform treatment planning.

- Questions included in the assessment should identify the specific drugs a person uses, including alcohol and tobacco, and the frequency, recency, and intensity of use.

The assessment should create a fuller picture of how the individual has experienced negative consequences of substance use; whether substance use has affected the person’s:

- physical health,

- mental health,

- family relationships, and work or career;

- whether substance use has led to any legal problems; and

- what effect it has had on housing.

Treatment History

(SAMHSA, 2007)

- The assessment should also include information about an individual’s past efforts to get treatment or quit independently.

- Questions should be asked about the events and behaviours that led to a person’s return to substance use after periods of abstinence.

- Similarly, fully exploring the features of successful quit attempts can help guide treatment plan decisions.

- Questions should be geared to type of treatment settings, whether support groups were used or might prove to be helpful, and other relapse prevention strategies the individual has used.

Social History

(SAMHSA, 2007)

Information about a person’s social environments and relationships can also assist in treatment planning.

- Social factors may influence:

- treatment engagement and retention,

- guide treatment planning, and

- affect prognosis.

- Questions should include those around transportation and childcare needs, stability of housing, and criminal or legal involvement.

- The assessment should include employment status and quality of work environment (positive or negative, as in stress).

- Question should be asked about close and/or ongoing relationships with people who use opioids.

- Details should be included about drug use from people the client lives or spends time with. NOTE: it is critical to obtain the person’s written consent before gathering this information.

- The assessment should consider of a person’s sexual identity or identities.

- The safety of the home environment (whether violence, abuse, or neglect are present) should be assessed as substance use disorder substantially increases the risk for intimate partner violence. It is advised to screen all women presenting for treatment for domestic violence.

Family History

(SAMHSA, 2007)

This subsection of assessment asks open-ended questions related to substance use histories of the person’s parents, siblings, partners, and children.

- Research shows that one of the strongest risk factors for developing opioid use is having a parent with a substance use disorder.

- Generational trauma and pain should be considered.

- It is important to involve the family in the initial assessment.

- Genetic factors, exposure to substance use in the household during childhood, or both can contribute to the development of substance use/misuse.

Open-ended, thought-provoking questions encourage clients to explore their own experiences. Ask questions like “In what ways has oxycodone affected your life?” Closed-ended questions with yes/no answers, such as “Has oxycodone caused your family trouble?” can feel judgmental to clients who may already feel ashamed and defensive. Closed-ended questions do not help clients become aware of and express their own circumstances and motivations, nor do they encourage clients to identify what they see as the consequences of their substance use.

NOTE: A physical exam is also part of an assessment but is outside the scope of this module.

The Importance of Involving Families

"Addiction cannot be understood from an isolated perspective. It is a complex human condition rooted in the individual’s experience the multi-generational history of his or her family, and in the cultural and historical context in which the individual and family have existed."

- Involving significant others and family members is part of a more holistic view on substance use that moves away from viewing substance use as an individual action or behaviour.

- Families do not have to be biologically related; the nature of substance use ruptures relationships and communication to the degree that the person using drugs may have no contact with other family members.

- Although drug use has traditionally been identified as a family disease, until recently, treatment approaches have primarily focused on helping the individual who has a substance use disorder.

- Although family members are often viewed as the support system for the individual using a substance, they may be experiencing their own challenges, which leave them feeling vulnerable.

- For this reason, it is critical to actively engage both the individual and family members from the beginning, starting with assessment, to ensure all parties feel heard and supported.

- Family members have useful information on why situations or experiences may have resulted in the use of a substance and how the use developed or is maintained.

- This kind of information is usually collected during the assessment phase and is guided by theories such as:

- attachment (Schindler, 2019),

- brief strategic family therapy (BSFT) theory (Szapocznik et al., 2013),

- and by approaches such as:

- trauma-informed care (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2014), or

- the person-centred approach.

- This kind of information is usually collected during the assessment phase and is guided by theories such as:

- Because substance use is often linked to intergenerational violence and trauma, some family members may be especially uncertain of how to proceed because of unresolved past issues.

- Studies show patterns of substance use and treatment readmission across generations related to gender, ethnicity, employment, and geographical region (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2015).

Why the Family’s Life Cycle Stage is Important

Understanding the family's developmental stage can help with assessing the needs of both the individual and the family.

- Carter and McGoldrick (1989) identify eight stages of the family life cycle and corresponding developmental tasks, as shown in Table 1.

- Substance use can impede or become a barrier to progressing through the stages, depending upon when in the life cycle stage drug use becomes an issue.

- When families stop moving through the life cycle, individual members can exhibit unhealthy symptoms such as substance use or abuse, as shown in Table 1.

- Family communication patterns change as a result of substance use disorder (SUD), reducing feelings of support, trust, honesty, acceptance, and empathy.

- Stigma associated with opioid use can result in both the individual and the family becoming isolated, which can perpetuate the issue and create barriers for seeking help.

- Including family members with the individual during the assessment stage may help identify how the family is coping with the substance use and lead to the exploration of healthier ways of communicating and healing.

- Encouraging people to share their feelings related to their experiences in the family is important, as it helps them to break the silence often associated with living with SUD. It can also increase awareness about cognitive and behavioural patterns that contribute to or maintain the SUD in the family unit.

Table 1 identifies the stages a family moves through developmentally, and how it changes when substance use disorder (SUD) is present.

| Stage | Developmental Tasks | Impact of SUD on Developmental Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Married without children | Establish a healthy marriage with a boundary from the family of origin. | Poor communication, impairment of emotional and physical intimacy, increased conflict |

| Stage 2: Childbearing families | Create a safe, loving home for an infant and the parents. Establish secure attachment with the child. | Home not physically or emotionally safe because of impairment and labile mood; insecure attachment with infants |

| Stage 3: Families with preschool children | Adapt to the needs of preschool children and promote their growth and development. Cope with energy depletion and lack of privacy. | Inconsistent parenting, possible abuse, neglect, Child Protective Services involvement, removal of children, marital conflict |

| Stage 4: Families with school-age children | Fit into the community of school-age families. Encourage children's education. | Educational needs of children not met, possible domestic violence, conflict at home |

| Stage 5: Families with teenagers | Balance freedom with responsibility. Establish healthy peer relationships. Develop educational and career goals. | Teens may follow model of parent with SUD; children have difficulty forming healthy peer relationships because of impaired early attachment; school/legal problems and family conflict; anxiety, depression, or oppositional disorders |

| Stage 6: Families launching young adults | Release young adults with appropriate assistance. Maintain supportive home base. Young adults develop careers. | Failure to launch because adult children cannot support themselves, relationship conflict |

| Stage 7: Middle-age parents | Rebuild the marriage. Maintain ties with younger generations. | Marital conflict, adult children may disconnect from parents and not want them around their young children |

| Stage 8: Aging family members | Cope with bereavement and living alone. Close the family home or adjust to retirement. | Isolation, depression can lead to SUD or vice versa |

Adapted from Lander et al. (2013)

What Does Whole Family Care Look Like?

- People define who their family members are. A family includes the supportive network of relatives as well as others whom the person identifies as part of their family.

- Whole family care is an approach that progresses beyond the assessment stage and involves continuing support to family members (as defined by the person using drugs) throughout many stages of treatment and recovery.

- Stages/components of treatment include:

- clinical treatment,

- clinical support,

- community support services that address substance use,

- mental health,

- physical health, and

- developmental, social, economic, housing, and environmental needs.

- Stages/components of treatment include:

- Treatment is based on the unique needs and resources of individual families. The goals, interventions, type, length, frequency, location, and method of services vary depending on the strengths and needs of the family members.

- Families are dynamic, and so treatment must also be dynamic. Treatment must be able to address evolving and changing family engagement. Members may not participate at the same time, stay the same length of time, or have the same motivations.

- Conflict is inevitable but often resolvable. Families must juggle conflicting priorities and balance the needs of members.

- Meeting complex family needs requires coordination across systems. Families with substance use disorders are often involved in multiple service delivery systems (e.g., child welfare, health, criminal justice, education).

- Substance use disorders are chronic but treatable. The treatment process is a gradual one that moves individuals and families towards recovery.

- Treatment includes a broad continuum of programs and strategies designed to address dependence, reduce adverse consequences associated with substance use, and return healthier functioning.

- Behavioural therapies, motivational enhancements, pharmacological interventions, and case management are common elements of treatment.

- Services must be gender responsive, specific, and culturally competent. Services must be grounded in and use the knowledge and skills that fit the background of individuals and families.

- Gender-responsive services recognize the unique characteristics of women’s initiation of use, effects of use, histories of trauma, co-occurring mental health and physical disorders, and other treatment issues, including the primacy, importance, and continuity of relationships in women’s lives.

- Maintaining a safe environment for all family members is essential. Maintaining trauma-informed and trauma-sensitive services and treatment milieu is paramount.

- Treatment must support the creation of healthy family systems. Healthy family systems include:

- structure,

- appropriate roles, and

- good communication.

These elements allow the family to function as a unit, while concurrently supporting the needs of each individual member.

Needs of Communities and Support Networks

In response to the opioid epidemic, many communities have developed comprehensive opioid-related plans, including many activities to address prevention, treatment, harm reduction and enforcement, or justice interventions across multiple socioecological levels, involving multiple sectors.

- Issues relating to opioid use span multiple sectors: medicine, health, well-being, housing, employment, personal and family supports, law enforcement, etc. It is imperative for individuals and agencies within and across each sector to know and understand the roles others play, to work together, and to avoid conflicting messages and actions.

- The needs of communities vary across the population and across the sectors that impact social determinants of health. The different needs of each community may require action and partnership from different sectors.

- Many regions and municipalities work to align and engage sector cooperation with the establishment of drug task forces or drug strategies.

- One of the first drug strategies in Canada was established in Vancouver in 2000, followed by other cities and municipalities.

- This strategy uses a four-pillar approach:

- Prevention

- Treatment

- Enforcement

- Harm Reduction

- This strategy uses a four-pillar approach:

- For more information on each pillar with examples, please see Four Pillars (Haliburton, Kawartha Lakes, Northumberland Drug Strategy, n.d.).

- Many regions and municipalities have developed drug strategies tailored to the needs of a particular community, designed to guide improvements in services and approaches to substance use.

- Since 2015, many of these have developed opioid-specific task forces to address the opioid crisis.

- For example, in Waterloo Region, Ontario, the Waterloo Region Integrated Drugs Strategy partnered with Region of Waterloo Public Health and Emergency Services to develop an opioid response plan (Waterloo Region Integrated Drugs Strategy Special Committee on Opioid Response, 2018).

- A scoping review found that community plans are often spearheaded by public health agencies and community-based organization (Leece et al., 2019).

- Community members should be aware of all local organizations that provide different services to address opioid crises.

- Various partners must be involved (health care, law enforcement, public health), and advisory committees are formed to solidify decision-making.

- Funding is most often received from the province or territory and from other sources, including non-profit organizations, the private sector, and university grants.

- Strategies implemented most often included overdose trainings, naloxone use, and data monitoring.

Questions

For each family development stage, match one corresponding SUD impact that is emphasized during times of opioid use.

Married without childrenFamily with pre-school children

Family with teenagers

Aging family members

Correct! The following are the correct family development stage and SUD matches:

- Married without children → Poor communication

- Family with pre-school children → Possible abuse and neglect

- Family with teenagers → Difficulty with peer relationships

- Aging family members → Isolation and depression

Incorrect. The following are the correct family development stage and SUD matches:

- Married without children → Poor communication

- Family with pre-school children → Possible abuse and neglect

- Family with teenagers → Difficulty with peer relationships

- Aging family members → Isolation and depression

References

Balint, E. (1969). The possibilities of patient-centered medicine. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 17(82), 269–76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2236836/

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2014). Trauma informed care. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Trauma-informed-Care-Toolkit-2014-en.pdf

Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (Eds.). (1988). Overview. The changing family life cycle: A framework for family therapy (2nd ed., pp. 3–28). Gardner Press.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2004). What is substance abuse treatment? A booklet for families. https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4126.pdf

Dardess, P., Dokken, D. L., Abraham, M. R., Johnson, B. H., Hoy, L., & Hoy, S. (2018). Partnering with patients and families to strengthen approaches to the opioid epidemic. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. https://www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/opioid-epidemic/IPFCC_Opioid_White_Paper.pdf

Fortin VI, A. H., Dwamena, F. C., Frankel, R. M., & Smith, R. C. (2002). Smith’s patient-centered interviewing: An evidence-based method (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Companies.

Goulao, J., & Stover, H. (2012). The profile of patients, out-of-treatment users and treating physicians involved in opioid maintenance treatment in Europe. Heroin Addiction & Related Clinical Problems, 14(4), 7–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261879267_The_profile_of_patients_out-of-treatment_users_and_treating_physicians_involved_in_opioid_maintenance_treatment_in_Europe

Haliburton, Kawartha Lakes, Northumberland Drug Strategy. (n.d.). Drug strategy: Four pillars. http://hklndrugstrategy.ca/four-pillars/

Lander, L., Howsare, J., & Byrne, M. (2013). The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice. Social Work in Public Health, 28(3–4), 194–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.759005

Leece, P., Khorasheh, T., Paul, N., Keller-Olaman, S., Massarella, S., Caldwell, J., Parkinson, M., Strike, C., Taha, S., Penny, G., & Henderson, R. (2019). “Communities are attempting to tackle the crisis”: A scoping review on community plans to prevent and reduce opioid-related harms. British Medical Journal, 9(9), e028583.

Lipkin, M. (1984). Suggestion and healing. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 28(1), 121–26. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.1984.0007

MacPherson D. (2001). Framework for action: A four-pillar approach to drug problems in Vancouver. City of Vancouver. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242480594_A_Four-Pillar_Approach_to_Drug_Problems_in_Vancouver

Maté, G. (2015). Foreward. In M. Herie & W. Skinner (Eds.), Fundamentals of Addiction. (3rd ed., pp. xiv-xvii).

Mead, N., & Bower, P. (2000) Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 1087–110.

Nicolaidis, C. (2011). Police officer, deal-maker, or health care provider? Moving to a patient-centered framework for chronic opioid management. Pain Medicine, 12(6), 890-897. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01117.x

Picker. (1993). Principles of patient-centered care. https://www.picker.org/about-us/picker-principles-of-person-centred-care/

Quantum Units Education. (n.d.). Opioid use disorder: Medication, screening and assessment for social workers.

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2015). Engaging clients who use substances.

Rezai-Zadeh, K. P., Engstrom, R. N., Sharma, A., Chen, Y., Chu, J., Cox, R. P., & Lee, M. T. (2019). Generational trends and patterns in readmission within a statewide cohort of clients receiving heroin use disorder treatment in Maryland, 2007–2013. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 96, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.10.010

SAMHSA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2007). Family-Centered Treatment for Women With Substance Use Disorders - History, Key Elements, and Challenges. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/family_treatment_paper508v.pdf

Schindler, A. (2019). Attachment and substance use disorders—Theoretical models, empirical evidence, and implications for treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(727). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00727/full

Szapocznik, J., Zarate, M., Duff, J., & Muir, J. (2013). Brief strategic family therapy: Engaging drug using/problem behavior adolescents and their families into treatment. Social Work and Public Health, 28(3–4), 206–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.774666

Vancouver Coastal Health. (2018). Response to the opioid overdose crisis in Vancouver Coastal Health. http://www.vch.ca/Documents/CMHO-report.pdf

Waterloo Region Integrated Drugs Strategy Special Committee on Opioid Response. (2018). Waterloo Region opioid response plan.

Werner, D., Young, N. K., Dennis, K., & Amatetti, S. (2007). Family-centered treatment for women with substance use disorders—History, key elements, and challenges. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/family_treatment_paper508v.pdf