Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe the uniqueness of the reasons for use and experiences of people who use opioids.

- Explain why one single approach to treatment is not helpful for all.

Key Concepts

- Every story of substance use is different, and treatment must be tailored to the person.

- The experiences of those who use drugs should not be generalized.

- Treatment is a complex and evolving term that has multiple meanings.

- It is important to understand and appreciate the unique circumstances and narratives of each person.

- Treatment preferences are equally as unique, and paying attention to this will ensure better and more person-centred outcomes and success.

Understanding the Uniqueness of the Lived Experience

Each story of opioid use is different, and the contributing reasons and treatment goals will be different as well.

To appreciate these differences, listen to actual stories by clicking the link. Listen to the “The Truth about Painkillers” and “The Truth about Prescription Drugs”

“At the age of twenty, I became an addict to a narcotic which began with a prescription following a surgery. In the weeks that followed [the operation] in addition to orally abusing the tablet, crushing it up enabled me to destroy the controlled release mechanism and to swallow or snort the drug. (It can also be injected to produce a feeling identical to shooting heroin.) The physical withdrawal from the drug is nothing short of agonizing pain.”

— James

“I didn’t think I had a ‘drug problem’—I was buying the tablets at the chemist [drug store]. It didn’t affect my work. I would feel a bit tired in the mornings, but nothing more. The fact that I had a problem came to a head when I took an overdose of about forty tablets and found myself in the hospital. I spent twelve weeks in the clinic conquering my addiction.”

— Alex

“Pretty much as long as I can remember I’ve had highs and lows. I would get easily upset by the littlest things, I would have anger outbursts, or hate someone for no reason at all. For a long while I had thought I was bipolar. I started using drugs last October to help me with my unwanted feelings. But believe it or not, it just made stuff worse! I had to now deal with my addiction and my emotional problems.”

— Thomas

“I realized after about a year I was addicted. When I decided to quit, I went through withdrawals physically, psychologically, and emotionally. I thought when I was on the pills full time (up to four a day), that I could do anything. They actually seemed to keep my mood steady and balanced. Ever since I have been off the pills, I feel more alive, alert and more capable of walking through life with confidence. I did not realize I had kept myself in an illusion or haze with the pills of false happiness.”

— Jason

“A ‘friend’ of mine turned me on to Oxys. I started with 40 mg tabs, then after a couple of months I bumped up to 60 mgs. I was really addicted by this point and started chewing them to get off quicker. Had to have one in the morning when I got up or I’d be sick. Had to have another before noon. Then a couple more in the afternoon and evening. I knew I was hooked because I had to have them to function. I felt horrible without them. Not only physically, but I couldn’t deal with people or life without them. Then I went to 80 mgs and my world came tumbling down. I started stealing from everyone I knew to get my fix.”

— Charleen

Avoiding Generalization of Treatment

Just as experiences are different with substance use, so too are experiences of treatment. Treatment success is often seen as an ambiguous term with multiple meanings.

For example, treatment success could mean:

- finishing an inpatient program,

- continuing a lifelong maintenance program,

- attending a community support group, or

- not losing employment while using.

There is no universal timeframe in which treatment is deemed a “success,” which further adds to the ambiguity of the term.

Some suggest that treatment rates are constructed to infer success only for policy and/or funding reasons.

Treatment outcomes depend on:

- the extent and nature of the person’s substance use,

- how treatment is tailored to the individual, and

- the quality of interaction between the persons and the health and social service providers who are working with them.

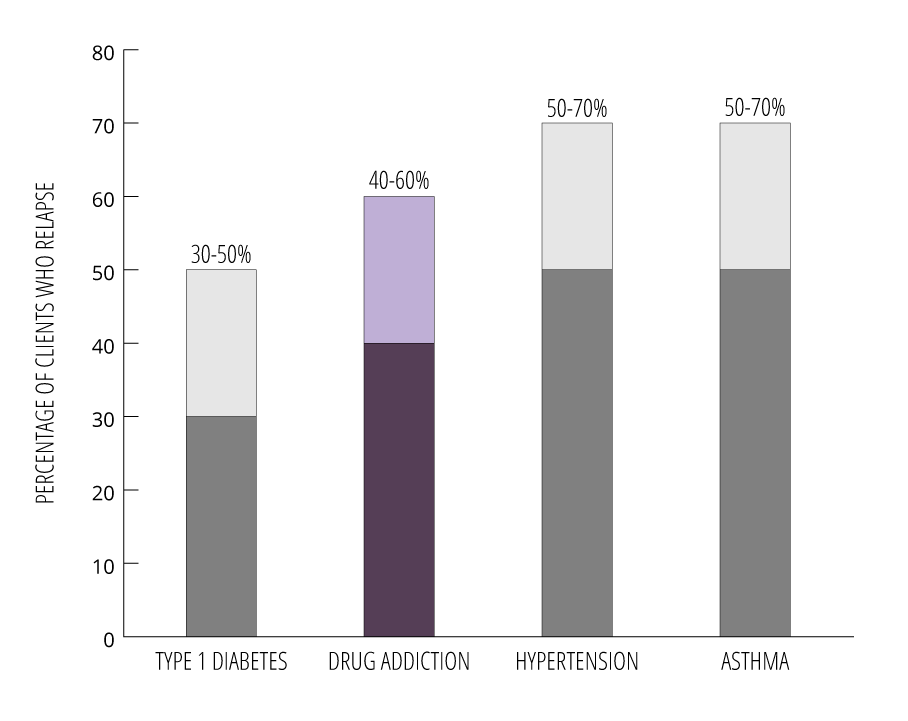

Relapse rates for persons with substance use disorders resembles those of other chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (2018)

Treatment and the treatment experience can be used by some people to make significant life changes, including channelling past experiences with using drugs into helping others.

Using lived experience with a disease to then help others is referred to as an illness narrative and may be part of reconstructing a life away from the addiction or substance use disorder.

Three examples of such narratives are provided below.

1. Chase Holleman returned to school to become a social worker. See Chase Holleman talk about his personal experience with drug use and becoming a social worker to help others with opioid use.

2. Brittany Sheldon authored a book of her substance use disorder and recovery titled Discovering Beautiful. Read an excerpt from Brittany Sheldon’s book Discovering Beautiful:

Discovering Beautiful

I am in long-term recovery from shame and perpetual escape.

This means no drugs and alcohol- no running. No unhealthy coping.

I kicked my inner-victim out on its ass and have been healing from the damaging effects of childhood trauma and self-destruction ever since.

I'm a believer in the kind of Truth that can set a person free, but only because I have experienced it for myself.

I live with my husband and three young boys. I am a wife and mom first.

In my spare time I write books and serve with the talents and skills God has purposed me with. I have a passion for breaking cycles and patterns and helping others overcome their fear of breaking away from their comfort zone.

— back cover, paperback edition —

3. Marc Lewis went from struggling with drug addiction to becoming a university professor. Listen to Marc Lewis speak on his experience of addiction and the concept of trust.

Narratives or stories shared by people who have lived experience with substance use disorders allow for a close and nuanced view into the intricate ways that substances changed their lives and their relationships with others.

Their stories represent knowledge gained from lived experience and are slowly being recognized as important sources of information that health and social service providers need to listen to and respect.

As an example, the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control considers individuals with lived experience as “the experts in the reality of drug use”. They believe that the engagement of individuals with lived experiences

“is a critical component of effective program and policy development to reduce substance-related harms. Their lived experience means they can identify the needs of their community and what is acceptable to people who use drugs”

Questions

References

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2004). What is substance abuse treatment? A booklet for families (HHS Publication No. SMA14-4126). https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4126.pdf

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018). Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide (3rd ed.). https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition

Pierret, J. (2003) The illness experience: State of knowledge and perspectives for research. Sociology of Health and Illness, 25(3), 4–22.

Provincial Health Services Authority. (2018). People who use drugs play a critical role in responding to overdoes. http://www.phsa.ca/about/news-stories/stories/people-who-use-drugs-play-a-critical-role-in-responding-to-overdoses

Sheldon, B. L. (2018). Discovering beautiful: Finding freedom from childhood trauma and self-destruction.