Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Review the components of a multidimensional contextual assessment.

- Discuss collaboration in the context of interdisciplinary care for persons on opioids and persons with an opioid use disorder.

Key Concepts

- Multidimensional assessments that are contextualized to an individualized experience contribute to the development of a comprehensive and person-centred plan of care.

- A comprehensive health history and physical examination including best possible medication history and/or medication reconciliation are components of a multidimensional assessment.

- Screening tools that are relevant to an individual’s context may be included in a multidimensional assessment.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration is essential in multidimensional assessment process.

- Interdisciplinary collaborative practice and care involves health professions working together toward a common goal.

Understanding Multidimensional Contextual Assessment

A multidimensional assessment helps providers identify the contribution of different dimensions of a person’s experience to symptoms and conditions as well as risk for health challenges. The multidimensional assessment process involves bringing together information from multiple sources and including the input of other interdisciplinary team members.

Comprehensive care planning based on the components of this assessment are person-centred (refer here to Topic A) and contextualized.

The need for this approach to assessment is well established in interdisciplinary pain care (Katz & Melzack, 1999; McGuire, 1992; Gibson et al., 2020), care of the elderly (Fletcher, 1998) and in the care of persons with substance use disorders (Vassileva & Conrod, 2019; ASAM, 2020).

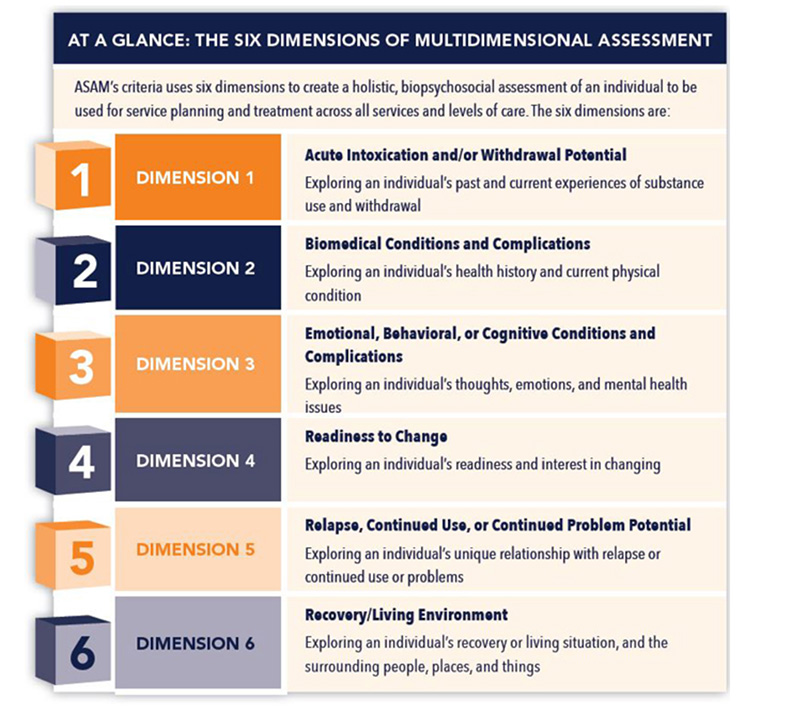

Although the components of a multidimensional assessment will vary by focus (See Figure 1 below), there are some commonalities to consider.

The initial step in the multidimensional assessment is to take a comprehensive health history. A comprehensive health history will include the chronology of any condition-related events, previous and current therapies, and all relevant medical, surgical, and mental health problems. Any previous imaging and diagnostic testing are included as well as reports from other health providers where possible. Some templates exist to organize some of this information: an example of a general form can be found here for use with adults.

A comprehensive health history also includes current and prior use of prescription and non-prescription medications, alternative therapies, allergies and previous adverse reactions. A best possible medication history and if possible, medication reconciliation should be performed. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada has an excellent guide for conducting the . This component of the multidimensional assessment may be completed by or include contributions from a clinical pharmacist.

Screening and assessment tools found in Topics A and B of this module can provide key information to inform the multidimensional assessment.

Complete or focused physical examination should be included in the multidimensional assessment: this may be done by a single provider or in components by discipline. For example, a physiotherapist contributes valuable information to a musculoskeletal assessment.

Interdisciplinary team members all contribute important information to the multidimensional assessment. In the care of persons who use opioids and persons who have an opioid use disorder, the interdisciplinary team may involve Registered Nurses and Nurse Practitioners, Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Social Workers, Psychologists, Addiction Counsellors, Pharmacists and Primary Care and Specialist Physicians. In many cases, it is also important to include the client and family caregivers as part of the team consistent with adopting a person-centred approach to care. (back to Topic A)

Figure 1. American Society of Addiction Medicine Six Dimensions of Multidimensional Assessment

Understanding Interdisciplinary Care

There is a difference in focus between ‘multidisciplinary’ and ‘interdisciplinary’ care (Stanos & Houle, 2006).

Multidisciplinary care may involve one or two providers (ie, Primary Care Physician and a Registered Nurse) directing the assessments and treatments provided by a number of other health team members who may have their own independent goals.

An interdisciplinary care model is in place when team members work together toward a common goal. These providers perform collaborative assessments and therapeutic decisions, have care team meetings to increase communication and to consult with each other.

Watch Physiotherapist Kathryn Schopmeyer explain a focus on interdisciplinary care during US PainWeek (please note this is US centric but the explanation is important).

Interdisciplinary care is dependent upon good interprofessional collaboration.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework for interprofessional education and collaborative practice includes the position that Collaborative practice happens when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, carers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings (WHO, 2010).

According to the World Health Professions Alliance (WHPA), the following broad principles must be in place for interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP) to occur and be effective:

- Policies and governance structures to facilitate and support opportunities for ICP

- Health system infrastructures enable ICP

- Education programmes and opportunities promote and facilitate shared learning

- ICP policies and practice are based on sound available evidence

Additionally, the WHPA affirms that the professional practice of all team members must be focused on the needs of the individual, recognising the skills and attributes that each of the collaborating professions contributes. Specifically, the WHPA include the following:

- ICP supports person-centred practice.

- By placing the focus on the needs of individuals, their families and communities and recognising they are part of the collaborative team, professional differences are minimised, and shared decision making happens in partnership.

- ICP requires mutual respect, competence, trust and synergy among team members.

- Professionals, sharing a common purpose, recognise and respect each other’s body of knowledge, role and team-agreed responsibilities.

- When the individual contributions of all professionals are recognised, there is more likely to be appropriate and timely referral and a good matching of competencies to a person’s needs.

- When there are overlapping scopes of practice, collaborative teams ensure that the professional with the best match of expertise to the needs of the individual is engaged at the appropriate time.

- ICP requires effective communication, enhanced by team members talking and actively listening to each other and to the individual concerned and his/her significant others.

Read the Canadian Nurses Association position statement on Collaborative Practice.

Stop and Think

Now that you have reviewed this content, consider the following:

Why is it important to collaborate with other health professionals when caring for persons on opioids and persons with opioid use disorder?

How does interprofessional collaboration contribute to the process of multidimensional assessment of clients in the context of opioid use and opioid use disorders?

Discuss your answers with your peers and mentors in light of the information shared in this content.

References

American Society of Addiction Medicine (2020). The ASAM National Practical Guideline for the Treatment of opioid use disorder: A focused update. Retrieved from: https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/quality-science/npg-jam-supplement.pdf?sfvrsn=a00a52c2_2 (2020).

Canadian Nurses Association (2011) Position statement: Collaborative Practice. Retrieved from: https://cna-aiic.ca/-/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/interproffessional-collaboration_position-statement.pdf?la=en&hash=5695B7264EB8EE6FA1A4B1A73A44A052F0FEA40F

Fletcher A. (1998). Multidimensional assessment of elderly people in the community. British Medical Bulletin, 54(4):945-60.

Gibson, K.A., Castrejon, I., Descallar, J., Pincus, T. (2020). Fibromyalgia Assessment Screening Tool: Clues to Fibromyalgia on a Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire for Routine Care. The Journal of Rheumatology 47, 761–769.

Katz J, Melzack R. (1999). Measurement of pain. Surgical Clinics of North America, 79(2), 231-52.

McGuire DB. (1992). Comprehensive and multidimensional assessment and measurement of pain. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management, 7(5):312-9.

Stanos, S., Houle, T.T., 2006. Multidisciplinary and Interdisciplinary Management of Chronic Pain. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America 17, 435–450.

Vassileva, J., Conrod, P.J. (2019). Impulsivities and addictions: a multidimensional integrative framework informing assessment and interventions for substance use disorders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Britain: Biological Sciences 374.

World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. Retrieved from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2F1BC2813585F0F5CB2FDA7598AF7BA4?sequence=1