Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Define a therapeutic relationship.

- Describe how the development of mutually trusting relationships with persons using opioids can positively impact treatment and outcomes.

- Explain the components of a therapeutic relationship.

- Describe how a humanistic approach can be used to develop a therapeutic alliance for health care and social service professionals.

Key Concepts

- The therapeutic relationship is a critical component in determining treatment outcome.

- Carl Roger’s humanistic theory and client-centred therapy are applicable when working with people using opioids.

- Components of Roger’s theory include unconditional self-regard, empathy, and congruence.

What Is a Therapeutic Relationship?

The therapeutic relationship or alliance between health and social service providers and clients is considered integral to positive change because it facilitates a greater therapeutic response (Orlinsky et al., 2004).

- In the psychotherapy literature, the therapeutic alliance is commonly defined as the “degree to which the therapy dyad is engaged in collaborative, purposeful work” (Hatcher & Barands, 2006, p. 293).

- Mottram (2009) defined a therapeutic interpersonal relationship as one that is perceived by others to encompass caring and supportive, nonjudgmental behaviour, embedded in a safe environment often during a stressful period.

The interpersonal dynamic of rapport is considered to be at the core of the therapeutic relationship between a client and the therapist. This dynamic was defined by Orlinsky and Howard (1986) as occurring when two people are on the same wavelength and care for each other's well-being.

- In a 2001 study involving 517 outpatient clients, characteristics of the therapist that encouraged the development of rapport included the terms “‘easy to talk to,’ ‘warm and caring,’ ‘honest and sincere,’ ‘understanding,’ ‘not suspicious” (Joe et al., 2001, p. 1224).

- When working with people with substance use or substance use disorder, a stronger therapeutic alliance has been linked to greater engagement, retention, and early improvements in substance use and distress (Gibbons et al., 2010; Lebow et al., 2006; Meier et al., 2005), as well as larger improvements in self-efficacy over the course of treatment (Hartzler et al., 2011).

- Diamond et al. (2006) found that the development of a strong alliance was particularly critical for treatment engagement and outcomes among youth with substance use, given their typically low levels of intrinsic motivation for change at treatment entry.

Humanistic Theory to Guide Establishing Therapeutic Relationships

Carl Rogers is known for his ground-breaking work in the development of humanistic or client-centred therapy, which focuses on essential components of the therapeutic relationship (Raskin & Rogers, 2005).

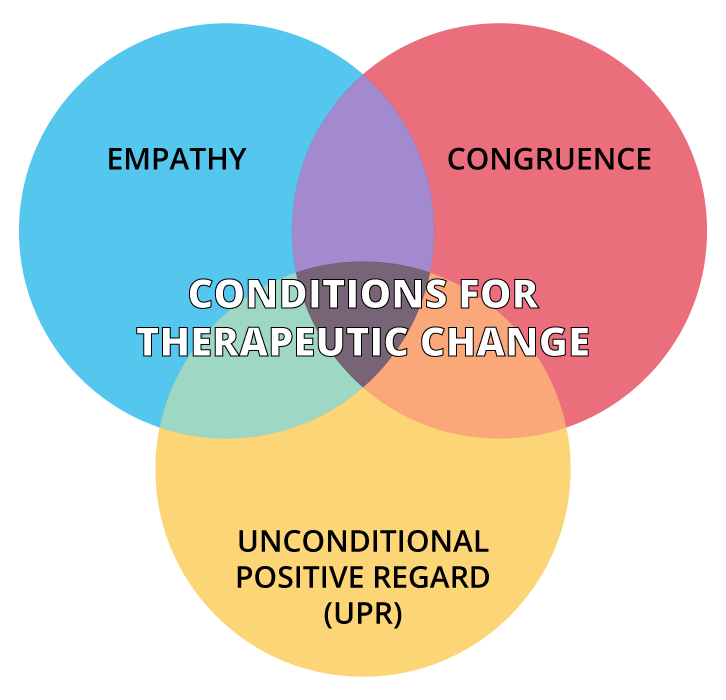

His humanistic theory focuses on three essential tenets as shown below: unconditional positive regard, empathy, and congruence.

Carl Roger’s Theory Regarding the Therapeutic Relationship

Raskin & Rogers (2005)

Unconditional Positive Regard

According to Rogers, unconditional positive regard involves the therapist showing unconditional support and acceptance of the person, no matter what the client says or does, placing no conditions on this acceptance.

Empathy

Definition

Empathy is defined as understanding another person’s experience by imagining oneself in that other person’s situation, without actually experiencing it (Ormont, 1999).

Empathy refers to the therapist's ability to understand sensitively and accurately (but not sympathetically) the person’s experience and feelings (Rogers, 1977).

An important part of accurate empathic understanding is the therapist conveying that they understand by reflecting the service user’s experience back to them. This encourages clients to become more reflective with themselves, which allows for a deeper understanding of themselves.

Congruence

The third tenet of Roger’s theory is congruence, meaning the therapist is authentic and genuine with clients. It is referred to as congruence because the therapist’s inner experience and outward expression need to match or be congruent.

By being perceived as authentic, the therapist builds trust with the client, which helps to form a good therapeutic relationship with the person using substances.

This also serves as a model for clients, encouraging them to be their true selves, expressing their thoughts and feelings, without any sort of false presentation. This learned behaviour also becomes part of the client’s healing process.

As congruence is the more difficult concept to understand in Roger’s theory, listen to how Professor Robert Elliot explains the concept below.

Within the context of working with persons who use opioids, unconditional positive regard for a client who uses drugs translates to assuming a nonjudgmental stance. Assuming this stance requires health and social service professionals to be aware of their bias and assumptions and not allow them to interfere in the therapeutic relationship.

If not addressed, the health and social service professional’s biases will surface in interactions with clients and impede the development of an alliance.

Some health and social service providers may feel that promoting the approach of harm reduction is uncomfortable as it is an abdication of the health-promoting responsibility (Bartlett et al., 2013).

If this unresolved bias continues to be present in the relationship, it may contribute to levels of societal shame and blaming, which then may be internalized by the client.

When clients perceive health and social service providers to be judgmental, clients may react in angry and hostile ways that are not helpful and can damage the therapeutic relationship.

- In this example, it may manifest in the person who uses opioids missing sessions, using inappropriate language when speaking to the health and social care provider, or becoming aggressive in speech or behaviour.

- Should this occur, it is important for the health and social care provider to spend time processing this issue and seek individual supervision or consultation with a peer or mentor.

Trust in Opioid Use/Misuse Counselling

Therapist congruence conveys the feeling of trust to the person who uses because the health and social service professional is perceived as being genuine.

What Happens When Trusting Relationships Are Formed

In a 2015 study involving 77 people using an opiate substitution treatment (OST), participants identified the development of trusting relationships with all treatment staff as the biggest difference maker in their treatment experience (Vanderplasschen et al., 2015).

The table below shows what clients identified as important features of the therapeutic relationship, including trust.

| Pharmacists | Physicians | Social Workers |

|---|---|---|

|

OST clients appreciated pharmacists’ personal commitment and trusting relationship. They expect accurate information from their pharmacist about the medication and being treated with respect and understanding as "normal" customers. Pharmacists who were flexible, (e.g., allowing a prescription to be picked up outside of normal opening hours) were seen as trusting. “The relationship with my pharmacist is very good. I never had problems. She is like a mum to all of us. She is really nice. It's not only: "Here are your drugs," but "How are you doing?” Whenever I have a problem, I can always go and talk to her about it.” |

More than half of the respondents stated their doctor played a central role in their treatment process, not only as prescriber but also as a person they can trust. The doctor's role goes beyond medical supervision; their moral support and personal involvement is welcomed. Thirty-five respondents identified their doctor as the most important person to them in treatment. Respondents reported that “being treated in a respectful and individualized way” by their physician was very important (p. 5). “We almost never talk about methadone, unless my dose is no longer ok. If I have problems in whatever area of my life, we talk about that, how everything is going. That's really of fundamental importance to me.” |

People using opioid replacement wanted to be seen as "normal people," rather than regarded as "unreliable" or "weak,” and wanted to have input in treatment decisions. When talking about desired psychosocial support, respondents most frequently mentioned the need to be able to tell their story to someone with whom they feel connected. Besides emotional support, respondents stressed the importance of practical support in OST (e.g., linking to ancillary services). |

Based on Vanderplasschen et al., 2015

What Happens When Trusting Relationships Are NOT Formed

In the same study as mentioned above, some people stated they were ashamed to ask their health and social service provider for help, for fear of having their request rejected. Some disclosed they had developed this feeling after many years of treatment by health and social service providers who no longer believed in their recovery and were not willing to continue investing time in them (Vanderplasschen et al., 2015).

Others felt interactions with health and social service providers were one dimensional, as highlighted by the following quote:

“It’s always drug use, drug use, drug use they want to talk about. But let us for once not talk about my drug use. I would appreciate it if they would have attention for what went well in my life and not always everything bad.”

A recurring theme from the study was that staff treated clients with respect. Vanderplasschen et al. (2015) concluded that the social stigma associated with drug use, and in particular opioid substitute treatment, has been shown to result in disrespectful and humiliating interactions with clients, jeopardizing the client’s sense of identity and recovery and impeding the establishment of trust.

Empathy in Substance Use/Misuse Counselling

A supportive and empathic counselling style is one of the keys to establishing an effective therapeutic alliance (Centre for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999). The therapist’s empathy enables clients to begin to recognize and own their feelings, an essential step toward managing them and learning to empathize with the feelings of others. While empathy is a critical component in all therapeutic relationships, studies show it may be more central in the development of a positive alliance when working with people who are using opioids. Proposed reasons why this is so for individuals with substance use/misuse are that they may:

- have lower motivation to work through substance use problems,

- face greater challenges in relating to others, and

- require more support for undertaking significant life changes (such as committing to abstinence) (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2005).

Empathy on the health and social service professional’s part helps:

“maintain the therapeutic alliance, increase client motivation, assist with medication adherence, model behaviour that can help clients build more productive relationships, and support clients as [they] make a major life transition”

Using Empathetic Language

Health and social service professionals’ use of empathic language can foster a therapeutic alliance. A study examining the use of specific words by the health and social service provider to demonstrate empathy during counselling sessions were perceived by clients as being more empathetic (Xiao et al., 2015).

The words shown in the table below were identified as having a higher value regarding empathy based upon a study that evaluated 200 counselling sessions using automatic speech recognition (Xiao et al., 2015). Words holding high empathy were also predictive of the quality of the therapeutic relationship.

| High Empathy | Low Empathy |

|---|---|

| it sounds like | during the past |

| do you think | using card a |

| you think you | past twelve months |

| sounds like you | do you have |

| that sounds like | some of the |

| sounds like it's | little bit about |

| p s is | the past ninety |

| what I'm hearing | first of all |

| one of the | you know what |

| so you feel | the past twelve |

| a lot of | please answer the |

| you think about | you need to |

| you think that | clean and sober |

| a little bit | have you ever |

| brought you here | to help you |

| sounds like you're | mm hmm so |

| you've got a | in your life |

| if you were | you have to |

| it would be | school or training |

Xiao et al., 2015

Questions

References

Bartlett, R., Brown, L., Shattell, M., Wright, T., & Lewallen, L. (2013). Harm reduction: compassionate care of persons with addictions. Medsurg Nursing: Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses, 22(6), 349–358.

Bozarth J. (2013). Unconditional positive regard. In M. Cooper, M. O'Hara, P. F. Schmid, & A. C. Bohart (Eds.), The handbook of person-centred psychotherapy and counselling (pp. 180–192). Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-32900-4_12

Brorson, H., Arnevik, E., Hendriksen, K., & Duckert, F. (2013). Drop-out from addiction treatment: A systematic review of risk factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1010–1024.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2005). Strategies for working with clients with co-occurring disorders. In Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 42) (Chapter 5). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64179/

Diamond, G. S., Liddle, H. A., Wintersteen, M. B., Dennis, M. L., Godley, S. H., & Tims, F. (2006). Early therapeutic alliance as a predictor of treatment outcome for adolescent cannabis users in outpatient treatment. American Journal on Addictions, 15(Suppl. 1), 26–33.

Gibbons, C. J., Nich, C., Steinberg, K., Roffman, R. A., Corvino, J., & Babor, T. F. (2010). Treatment process, alliance and outcome in brief versus extended treatments for marijuana dependence. Addiction, 105, 1799–1808.

Gibson, S. (2005). On judgment and judgmentalism: How counselling can make people better. Journal of Medical Ethics, 31, 575–577.

Hartzler, B., Witkiewitz, K., Villarroel, N., & Donovan, D. (2011). Self-efficacy change as a mediator of associations between therapeutic bond and one-year outcomes in treatments for alcohol dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022869

Hatcher, Robert & Barends, Alex. (2006). How a return to theory could help alliance research. Psychotherapy, 43, 292-9.

Joe, G. W., Simpson, D. D., Dansereau, D. F., & Rowan-Szal, G. A. (2001). Relationships between counseling rapport and drug abuse treatment outcomes. Psychiatric Services, 32(9), 1223–1229.

Lebow, J., Kelly, J. F., Knobloch-Fedders, L. M., & Moos, R. H. (2006). Relationship factors in treating substance use disorders. In L. G. Castonguay & L. E. Beulter (Eds.), Principles of therapeutic change that work (pp. 293–319). Oxford University Press.

Meier, P. S., Barrowclough, C., & Donmall, M. C. (2005). The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of substance misuse: A critical review of the literature. Addiction, 100, 304–316.

Mottram, A. (2009). Therapeutic relationships in day surgery: A grounded theory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18, 2830-7.

Orlinsky, D. E., & Howard, K. I. (Eds.). (1986). Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. Wiley Publishing.

Orlinsky DE, Rønnestad MH & Willutzki U. (2004). Fifty years of psychotherapy process-outcome research: Continuity and change. In: Lambert MJ, eds. Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 307-393.

Ormont, LR. (1999). Establishing transient identification in the group setting. Modern Psychoanalysis, 24(2), 143-156.

Petry, N. M., & Bickel, W. (1999). Therapeutic alliance and psychiatric severity as predictors of completion of treatment for opioid dependence. Psychiatric Services, 50(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.50.2.219

Raskin, N.j., & Rogers, C. R. (2005). Person-centered therapy. In R.J. Corsini & D. Wedding (Eds.). Current psychotherapies (p.130-165). Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Rogers, C. (1977). Carl Rogers on person power. Delacorte Press.

Simpson, D., Joe, G., Rowan-Szal, G., & Greener, J. (1997). Drug abuse treatment process components that improve retention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 14(6), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00181-5

Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health. (2014). Creating cultural safety. https://wabano.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Creating-Cultural-Safety.pdf

Vanderplasschen, W., Naert, J., Vander Laenen, F., & De Maeyer, J. (2015). Treatment satisfaction and quality of support in outpatient substitution treatment: Opiate users’ experiences and perspectives. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 22(3), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2014.981508

Xiao, B., Imel, Z. E., Georgiou, P. G., Atkins, D. C., & Narayanan, S. S. (2015). "Rate my therapist": Automated detection of empathy in drug and alcohol counseling via speech and language processing. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0143055. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143055