Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Define stigma and understand the different types of stigma.

- Describe the concept of health stigma as it applies to discrimination and stereotypes.

- Describe ways to help reduce stigma.

- Design/employ an anti-stigma approach that is regionally and culturally appropriate and model and advocate for non-stigmatizing behaviour.

- Describe how stigma can hinder the development of a trusting, compassionate, therapeutic relationship with persons using opioids or persons with opioid disorder, and significant others.

Key Concepts

- This module contains examples of binary gender and does not include transfemme, transmasc, nonbinary, or gender diverse experiences of stigma.

- The concepts of stigma and discrimination are distinct but related.

- Stigmatizing attitudes of health and social service professionals towards people with substance use problems may negatively affect health care delivery and could result in treatment avoidance or interruption during relapse.

- A greater degree of stigma is attached to substance use disorder as compared to other conditions.

- An intersectional approach to addressing stigma is best as it encompasses all systems at different levels and addresses multiple factors.

What Is Stigma?

Definition

- Stigmatization

- Stigmatization is defined by Link & Phelan (2001) as “a powerful social process that is characterized by labelling, stereotyping, and separation, leading to status loss and discrimination, all occurring in the context of power”. It can result in negative discrimination, which is “unfair and unjust action towards an individual or a group on the basis of real or perceived status or attributes, a medical condition, socioeconomic status, gender diversity, race, sexual identity, or age” (Nyblade et al., 2019, p.1).

Stigma affects individuals or groups both for health (e.g., disease-specific) and non-health (e.g., poverty, race, gender, age, gender identity, sexual orientation, migrant status) differences, whether real or perceived.

- Individuals who use/misuse opioids and their families often experience both stigma and discrimination.

- People who feel more stigmatized are less likely to seek treatment, even if they have the same severity of substance use disorder. They are more likely to drop out of treatment if they feel stigmatized and ashamed.

Research has shown that the more stigmatized the condition, as is the case with substance use disorders, the more likely the individual will self-stigmatize.

- Stigma may also make addiction worse. A 2014 study published in the Journal of Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research found that when people with substance use disorders perceived social rejection or discrimination, it increased their feelings of depression or anxiety (Kulesza et al., 2014).

Corrigan and O’Shaughnessy (2007), in their article “Changing Mental Illness Stigma as It Exists in the Real World,” identify three kinds of stigma:

Self-stigma

Stigma that individuals and consumers feel towards themselves, which can prevent people from seeking the support of family, peers, and professionals.

Public Stigma

Stigma that comes from the general public towards a stigmatized group and is learned early in life (Byrne 2000). Prejudices against people with mental health conditions permeate most social milieux and contribute to exclusion in subtle and blatant ways.

Structural Stigma

Stigma that is inherent in the policies of private and public institutions that restrict opportunities for people with mental illness. It is experienced as bias, avoidance, discomfort, and outright discrimination.

What Is Health Stigma?

Health stigma can be defined as “status loss and discrimination informed by negative attitudes and stereotypes based on health-related conditions” (Link & Phelan, 2001).

Individuals needing substance use treatment are a vulnerable group and may experience two types of stigma: enacted stigma and perceived stigma.

Enacted stigma refers to “overt rejection and discrimination and may include denial of housing and medical services, social isolation, and verbal and physical assaults” (Stringer & Baker, 2018).

As an extreme example, please take the time to read about the tragic event of Brian Sinclair’s death in the report below. It details the events leading up to his death and the inquest and recommendations that followed it. Brian Sinclair died after waiting for 34 hours at a Manitoba Hospital. Out of Sight

Perceived stigma is a “multidimensional concept that encompasses feelings of shame or embarrassment about having a stigmatized health condition and anticipation, and fear of, encountering social stigma” (Stringer & Baker, 2018).

- Social stigma is related to living with a specific disease or health condition and may be experienced in all spheres of life. However, Nyblade et al. (2019, p.1) stated that “stigma in health facilities is particularly egregious, negatively affecting people seeking health services at a time when they are at their most vulnerable.”

Language has the ability to inform stigma, as highlighted in a study by Kelly et al. (2010), who surveyed 314 individuals regarding their perceptions of individuals who use drugs. Study participants responded to a 35-item assessment comparing two phrases: substance abuser and having a substance abuse disorder.

- The results indicate that survey participants associated the term substance abuser with someone who “engaged in willful misconduct, is a greater social threat, and more deserving of punishment” (p. 814).

- The authors concluded that such strong and negative public perceptions act as a barrier for those individuals seeking help and reinforce stigma within health care settings.

Meanings Associated With Substance Use

In a study by the Recovery Research Institute, participants were asked how they felt about two people "actively using drugs and alcohol"

No further information was given about these hypothetical individuals.

THE STUDY DISCOVERED THAT PARTICIPANTS FELT THE "SUBSTANCE ABUSER" WAS:

- less likely to benefit from treatment

- more likely to benefit from punishment

- more likely to be socially threatening

- more likely to be blamed for their substance related difficulties and less likely that their problem was the result of an innate dysfunction over which they had no control

- they were more able to control their substance use without help

(Recovery Research Institute, n.d.)

Gender and Stigma

Women living with addictions experience the associated stigma differently from men (Canadian Women’s Health Network, 2009). A contributing reason for this outcome is that women who use drugs “do not conform to socially defined standards of feminine behaviour [and are] subjected to negative sanctions for their transgressions, including views of female users as being dirty, masculine, and sexually available” (Stringer & Baker, 2018).

- Research shows that female drug users face high levels of stigmatization in part because they violate the gender-role expectations (Lee & Boeri, 2017) of being “good” mothers, caretakers of others, more risk-averse, etc. Public discourses and policies surrounding pregnant women who use drugs have been found to be particularly judgmental, blaming, and unsympathetic (Greaves & Poole, 2005; Schmidt et al., 2019).

- Content analysis done by the British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (2005) and the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (2019) on media discourses and policy responses to women who use substances revealed “highly negative attitudes that reflect the perception that the women deliberately create their difficult predicaments, with little responsibility assigned to the system” or structural contribution. The stigma was greater for women who had substance use problems than for those with mental health or violence-related problems; the last two groups were portrayed as less responsible for their situation because their behaviour was regarded as out of their control, and the system was failing them (Greaves et al., 2004).

- The World Health Organization (n.d.) has concluded that “gender stereotypes regarding proneness to emotional problems in women and alcohol problems in men, appear to reinforce social stigma and constrain help seeking along stereotypical lines. They are a barrier to the accurate identification and treatment.”

- When exploring the differences between male and female users of methamphetamine, Lee and Boeri (2017) found that “while violence and excessive use were more prevalent behaviours among female than male methamphetamine users, women responded to treatment better than males did. Yet women users have limited access to treatment resources and face more challenges during recovery than do men” (Boeri et al., 2016; Maher & Hudson

Kirsty Prasad presents “Gender and Addiction” and talks about what is unique about women and substance use, as well as the barriers that women face. The presentation was sponsored by Alberta Health Services. Please watch the session below.

Intersecting Forms of Stigma and Discrimination

Beyond the stigma of being a drug user, people of all genders who have substance use concerns are stigmatized for the intersecting issues they face, such as:

- poverty,

- minority status,

- unemployment, and

- older age (Connera & Rosen, 2008; Lyons et al., 2015).

An intersectional approach seeks to understand an individual’s experience through the three circles depicted in the intersectionality wheel below.

inner ring

- unique circumstances, aspects of their identity i.e., disability, race, age, gender, housing situation)

outer ring

- types of discrimination they faced (i.e., racism, classism, ableism, ageism)

outside of the circle

- larger systems of power and oppression (i.e., colonization, capitalism, war, immigration system, legal system)

Intersectionality and Anti-Stigma Approaches

Intersectionality can be helpful as a contextual framework for examining and understanding the many influences on people’s experiences of opioid use and opportunities for seeking help. As shown below, the systems that shape experiences cannot be separated, even though they are often studied this way.

- By identifying and making explicit sites of power and privilege, interventions that disrupt the reproduction of power are the goal—those that interrupt stigma(s) experienced (racism, ageism, and sexism).

- Several models exist that offer anti-stigma approaches that are gender and culturally informed, and advocate for non-stigmatizing behaviour.

Morgan (1996) offers an intersectional framework to better identify and confront gender stigma based upon the premise that stigma originates from concurrent and multiple sites. It is a concept that emerged during the era of “second-wave feminism” and highlights the intersection of gender, sex, race, class, and disability.

Intersectional Model for Anti-Stigma Approaches

Approaches that work best to disrupt stigma are multi-pronged, concurrent and involve multiple levels of involvement starting with the individual health and social service provider and moving through structural factors, such as policies, social action, and justice initiatives aimed at changing practices that stigmatize vulnerable groups in society.

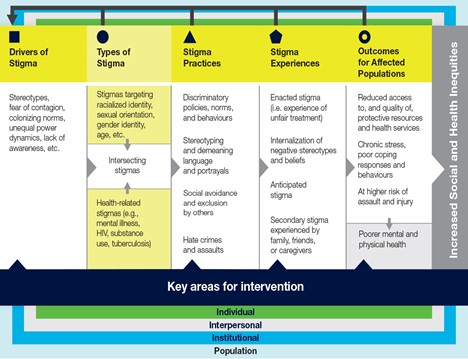

The Stigma Pathways to Health Outcomes Model (Stangl et al., 2019) visually describes the stigmatization process as it unfolds across the wider community and domains of health (see below). It makes visible how stigma is fluid and rooted within the individual, interpersonal, organization, community, and public policy domains. Efforts to reduce stigma must be enacted in each of these domains.

Stigma Pathways to Health Outcomes Model

Stigma pathways can be traced back to:

- Drivers such as stereotypes and fear

- Types of stigma (that can intersect) such as racialized identity, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, and health-related stigma such as mental illness, HIV, substance use and tuberculosis

- Stigma practices such as discriminatory policies, norms and behaviours, stereotyping and demeaning language and portrayals, social avoidance and exclusion and hate crimes and assaults.

- Stigma experiences, such as enacted stigma (unfair treatment), internalization of negative stereotypes and beliefs, anticipated stigma, and secondary stigma experienced by friends, family and caregivers

All of the above feed the outcomes for affected populations, such as:

- Reduced access to, and quality of, protective resources and health services

- Chronic stress, poor coping responses and behaviours

- Poorer mental and physical health

Key areas for intervention exist at the individual, interpersonal, institutional and population level.”

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Addressing stigma: Towards a more inclusive health system. The chief public health officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada, 2019. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/addressing-stigma-what-we-heard/stigma-eng.pdf

Questions

References

British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health & Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2005). Girls, women and substance abuse. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-05/ccsa-011142-2005.pdf

Boeri, M., Gardner, M., Gerken, E., Ross, M., & Wheeler, J. (2016). "I don't know what fun is": Examining the intersection of social capital, social networks, and social recovery. Drugs Alcohol Today, 16(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-08-2015-0046

Canadian Women’s Health Network. (2009). Understanding stigma through a gender lens. http://www.cwhn.ca/en/node/41610

Connera, K. O., & Rosen, D. (2008). “You’re nothing but a junkie”: Multiple experiences of stigma in an aging methadone maintenance population. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 8(2), 244–264.

Corrigan, P. W., & O'Shaughnessy, J. R. (2007). Changing mental illness stigma as it exists in the real world. Australian Psychologist, 42(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060701280573

Greaves, L., Pederson, A., Varcoe, C., Poole, N., Morrow, M., Johnson, J., & Irwin, L. (2004). Mothering under duress: Women caught in a web of discourses. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 6(1), 16–27.

Greaves, L., & Poole, N. (2005). Victimized or validated? Responses to substance-using pregnant women. Canadian Women's Studies Journal, 24(1), 87–92.

Kelly, J. F., Dow, S. J., & Westerhoff, C. (2010). Does our choice of substance-related terms influence perceptions of treatment need? An empirical investigation with two commonly used terms. Journal of Drug Issues, 40(4), 805–818.

Kulesza, M., Ramsey, S., Brown, R., & Larimer, M. (2014). Stigma among Individuals with substance use disorders: Does it predict substance use, and does it diminish with treatment? Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy & Rehabilitation, 3(1), 1000115. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-9005.1000115

Lee, N., & Boeri, M. (2017). Managing stigma: Women drug users and recovery services. Fusio: The Bentley Undergraduate Research Journal, 1(2), 65–94.

Lende, D. H., Leonard, T., Sterk, C. E., & Elifson, K. (2007). Functional methamphetamine use: The insider’s perspective. Addiction Research & Theory, 15(5), 465–477.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review Sociology, 27(1), 363–385.

Livingston, J. D., Milne, T., Fang, M. L., & Amari, E. (2012). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: A systematic review. Addiction, 107(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x

Lyons, T., Shannon, K., Pierre, L., Small, W., Krüsi, A., & Kerr, T. (2015). A qualitative study of transgender individuals’ experiences in residential addiction treatment settings: Stigma and inclusivity. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 10(1), 1.

Maher, L., & Hudson, S.L. (2007). Women in the drug economy: A metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. Journal of Drug Issues. 805–826.

Matthews, S., Dwyer, R., & Snoek, A. (2017). Stigma and self-stigma in addiction. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 14(2), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-017-9784-y

Metcalf, H., Russell, D., & Hill, C. (2018). Broadening the science of broadening participation in STEM through critical mixed methodologies and intersectionality frameworks. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(5), 580–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218768872

Morgan, K. P. (1996) Describing the emperor’s new clothes: Three myths of educational (in)equity. In The gender question in education: Theory, pedagogy, & politics (pp. 105–122). Westview Press.

Nyblade, L., Stockton, M. A., Giger, K., Bond, V., Ekstrand, M., McLean, R., Mitchell, E., Nelson, R., Sapag, J., Siraprapasiri, T., Turan, J., & Wouters, E. (2019). Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine, 17(25). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2

Radcliffe. P. (2011). Motherhood, pregnancy, and the negotiation of identity: The moral career of drug treatment. Social Science & Medicine, 72, 984–991

Rance, J., & Treloar, C. (2015). “We are people too”: Consumer participation and the potential transformation of therapeutic relations within drug treatment. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(1), 30–36.

Recovery Research Institute (n.d.) The real stigma of substance use disorders. https://www.recoveryanswers.org/research-post/the-real-stigma-of-substance-use-disorders/

Roberts, G., Ogborne, A., Leigh, G., & Adam, L. (1999). Best practices: Substance abuse treatment and rehabilitation. Health Canada, Office of Alcohol, Drugs and Dependency Issues.

Schmidt, R., Wolfson, L., Stinson, J., Poole, N., & Greaves, L. (2019). Mothering and opioids: Addressing stigma and acting Collaboratively. Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. http://bccewh.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CEWH-01-MO-Toolkit-WEB2.pdf

Stangl, A. L., Earnshaw, V. A., Logie, C. H., Brakel, W., Simbayi, L., Barre, I., & Dovidio, J. (2019). The health stigma and discrimination framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine, 17(31). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3

Stringer, K. L. & Baker, E. H. (2018) Stigma as a barrier to substance abuse treatment among those with unmet need: An analysis of parenthood and marital status. Journal of Family Issues, 39(1):3-27.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Anti-stigma toolkit: A guide to reducing addiction-related stigma. https://attcnetwork.org/sites/default/files/2019-04/Anti-Stiga%20Toolkit.pdf

Villa, L. (2019). Shaming the sick: Addiction and stigma. American Addiction Centers. https://drugabuse.com/addiction/stigma/

Wakeman, S., & Rich, J. (2018). Barriers to medications for addiction treatment: How stigma kills. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(2), 330–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1363238

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Gender and women’s mental health. https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/