Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe how an understanding of cultural factors has positive impacts on care plans.

- Describe the types of cultural practices used in the treatment of opioid use disorder.

- Evaluate the evidence for the use of cultural practices in the context of addiction.

- Incorporate cultural practices and Western medical interventions into the plan of care.

Key Concepts

- Many health professionals lack knowledge about cultural interventions, their role, their efficacy, and how they can work in collaboration with biomedical treatments.

- Often, Western biomedical approaches are disease- and symptom-focused, not holistic.

- There is emerging evidence for the effectiveness of using cultural practices and biomedical interventions concurrently.

- Programming for Indigenous Peoples

- Working with Indigenous, provincial, and territorial partners to provide culturally appropriate services

- Increasing access to opioid agonist treatment options in some First Nations communities

- Supporting efforts to promote harm reduction initiatives based on the unique needs of First Nations and Inuit communities, including the availability of naloxone and naloxone training

Cultural Interventions and Western Medicine

The classic Western, or biomedical, approach to medicine involves the diagnosis of a disease state by set criteria (e.g., the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM), and treatments to correct that disease state.

- Treatment success occurs when the symptoms or indicators of a disease state are no longer present.

- Treatment failure occurs when the symptoms or indicator of a disease state persist.

Opioid treatment approaches are rooted in this same Western paradigm. This paradigm embraces values that are incongruent to Indigenous beliefs, such as:

- autonomy,

- independence,

- focus on harms,

- costs and benefits, and

- emphasis on success within discrete timeframes (Allan & Smylie, 2015).

The biomedical system often lacks a holistic approach to the wellness of the individual beyond physical or psychological systems and fails to incorporate emotional, spiritual, community, and other contributors to well-being (Lavallee & Poole, 2010).

In comparison, Indigenous methods value a holistic and communal approach that acknowledge the relationship with others and the land as healing elements (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.).

Cultural practices and interventions do take a holistic approach and can bridge gaps in treatments that originate out of biomedical-based medicine (Leyland et al., 2016).

Many health professionals lack knowledge about cultural interventions, their role, their efficacy, and how they can work in collaboration with biomedical treatments. Many health professional education programs offer limited information and discussion of such practices (Linklater, 2014).

- A scoping review of cultural interventions for treating addictions in Indigenous populations found that culture-based treatment services included spiritual health, sweat lodges, and traditional teachings (Rowan et al., 2014).

- In Canada, it is recognized that Indigenous traditional culture is vital for client healing and wellness by the Truth and Reconciliation commission (Morna, 2020).

Cultural Practices and Opioid Use

To highlight the differences between Western and Indigenous approaches, some approaches embraced by Indigenous peoples are identified below:

- Sweat lodge ceremonies

- Smudging (burning of one or more medicinal or sacred plants)

- Ceremonial burning of sage and other plant materials

- Fasting

- Land-based activities

- Recognizing the value of specific traditional lands, outdoor activity

- Social and cultural activities

- Working together on daily activities (e.g., shopping), spiritual practices, recreational activities (sports, crafts, nature-based activities, hunting, fishing), cultural activities (clothing, art, other objects)

- Welcoming feasts, full-moon celebrations

- Including community members in treatment centres

- Food-based security, sovereignty

- Traditional foods, ceremonial dinners

- Herbs and natural medicines

- Traditional teaching and storytelling

- Elder teaching

- Talking circles

- Singing, dancing, drumming

Effects of Fasting on Chronic Pain and Opioid Use

Intermittent fasting, which controls eating times within a restricted time frame, might be a non-invasive behavioural intervention to promote healthy neuroplastic changes (Sibille et al., 2016).

Chronic opioid use to treat pain symptoms carries a risk of developing into opioid use disorder through potential neurobiological changes. These neuroplastic/neurobiological changes might explain why pain becomes chronic in some individuals. The effects of fasting on opioid use and opioid use disorder are yet to be studied extensively; however, the benefits on chronic pain might help to reduce the dependence on opioid use.

Fasting as Cultural Practice

Long fasts that include restricting intake of solid foods have been practised for a long time around the world. Periods of deliberate fasting are common in several religious and cultural practices as fasting is seen to enhance mental and spiritual alertness. Fasting is a religious practice for Muslims around the world and has been a ceremony in many First Nations communities for thousands of years (Anishnawbe Health Toronto, 2011).

Fasting as Medical Treatment

Clinical trials in which calorie intake was restricted to 200–500 kcal/day from one to three weeks have been used to treat:

- chronic pain syndromes,

- rheumatoid diseases,

- hypertension, and

- metabolic syndrome (Michalsen, 2010).

Medically supervised modified fasting treatment may have positive benefits because of humankind’s evolutionary history of periods of starvation based on food availability. The exact physiological mechanisms that have evolved for humans to cope with extended periods of fasting are still not fully understood.

- A randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of alternate day fasting, and the authors found significant improvements after 16 weeks in emotional well-being, general health, physical functioning, and pain (Bowen et al., 2018).

- A study in Germany found that short-term therapeutic fasting for the treatment of chronic pain and fatigue syndrome was safe even without mineral supplements (Michalsen et al., 2002).

- Prolonged fasting might have positive effects on mood enhancement, possibly through the neuroendocrine response to physiological starvation signalling.

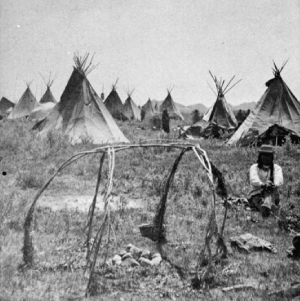

The Effect of Sweat Lodge on Opioid Use

Sweat lodge is a tradition of some Indigenous peoples where individuals enter a dome-shaped dwelling to experience a sauna-like environment. “The sweat ceremony is intended as a spiritual reunion with the creator and a respectful connection to the earth itself as much as it is meant for purging toxins out of the physical body” (Filice, 2017).

Huffman, L. Sweat lodge, Sioux Village / L. A. Huffman, Miles City, Montana [Online Image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SweatLodge.jpg.

James Mahan/iStock

- Marsh et al., (2018) found that “although sweat lodge ceremonies have historically been an important part of Indigenous cultures throughout North America, little evidence supports the efficacy of this intervention. However, there has been a revival of traditional Indigenous ceremonies, and both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples have increasingly used the sweat lodge ceremony as a means of healing in multiple dimensions of body, mind, emotion, and spirit”.

- Rowan and colleagues (2014) conducted a scoping review that included 189 studies from the United States and Canada. Seventeen types of cultural interventions were identified, with sweat lodge ceremonies the most commonly enacted (68 percent). Results show benefits in all areas including improvements in measures related to substance use in 74 percent of studies.

- Neurologically, sweating also has positive impacts on systems involved in stress, such as the sympathetic nervous system and stress hormone signaling (Hussain & Cohen, 2018).

- Marsh and colleagues (2018) and Schiff and Moore (2006) confirm that the inclusion of traditional healing approaches and the sweat lodge ceremony help with individuals’ healing spiritually, emotionally, and physically.

These healing approaches were reported to result in:

- A stronger sense of connection, release, and peace through the presence of ritual and healing practices, including the sweat lodge ceremonies

- A returning to the womb of Mother Earth

- Through the presence of the Elders, the Creator, and the Ancestors, deep-level healing by all participants

- Confirmed changes in health and wellness after the participation in a sweat lodge or sauna

- Enhanced immunity, help with sleep problems and pain management, and increased relaxation

- An Indigenous sweat lodge also has restorative and healing power on groups as it does the following (Marsh et al, 2018):

- Enhances mutual support among group members

- Encourages connection among participants

- Provides a deeply moving and truly spiritual experience, which results in physical, mental, and spiritual connection

“All the core content in the sweat lodge ceremonies was delivered to promote knowledge and understanding, as well as to create a space and place of healing. These ceremonies were offered to help participants to heal from internalized oppression, which represents one of the long-term effects of intergenerational trauma, or neocolonialism.”

Sweat lodge ceremonies increased openness to treatment. Individuals also:

“have the ability to discharge some of the gross traumatic energy that is stuck in the body through movement, vibrations, sweating, crying, and shaking. During the sweat ceremonies, many participants reported this sense of letting go and releasing through the heat and sweating”

Garrett and colleagues (2011) concluded that it would be:

“beneficial to incorporate Indigenous traditional healing practices, including the sweat lodge ceremony, into… comprehensive strategies to enhance the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples with substance use disorders”.

Traditional healing methods such as the sweat lodge ceremony may help Indigenous persons with opioid use disorder explore and reconcile issues around cultural identity (Garrett et al., 2011).

Evidence for Efficacy of Cultural Practices

Evidence for efficacy of cultural practices is still emerging, particularly when they are used in combination with biomedical treatments. Much of the literature for cultural practices in the context of substance use disorder comes out of studies involving alcohol use; however, previous evaluation of cultural practices has been hampered by:

- Limited methodological information

- A lack of control groups for comparison

- A focus on some outcomes (e.g., alcohol consumption) but not others (emotional and spiritual well-being)

A scoping review by Rowan and colleagues (2014) examined 19 studies, all of which included integrated treatment programs that incorporated cultural practices and Western medicine.

- Outcomes of these studies described spiritual, mental, emotional, and physical indicators.

- Overall, positive outcomes were reported across all four domains.

Despite methodological issues and insufficient research regarding the effects of cultural practices on addiction and use disorder, a growing body of knowledge suggests that treatment programs that incorporate aspects of cultural practices and Western medicine result in positive outcomes, not just with respect to the treatment of substance use disorder but also with improvements in mental, emotional, and spiritual outcomes.

First Nations Data Sovereignty

Because of past issues with informed consent, First Nations have sought data sovereignty and created the Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) principles to develop information and research that respects First Nations communities. Please take the time to become familiar with the First Nations Principles of OCAP, what they are, what they mean, why they are necessary, and how to apply them.

Stop and Think

Now that you have reviewed this content, consider the following:

List two important reasons for incorporating traditional Indigenous healing practices into biomedical health care practices.

Consider client-centered, practical ways this could be achieved.

References

Allan, B., & Smylie, J. (2015). First Peoples, second class treatment: The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Wellesley Institute. https://indigenousto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Research_Race_1b.pdf

Anushnawbe Health Toronto. (2011). Fasting. https://www.aht.ca/images/stories/TEACHINGS/Fasting.pdf

Bowen, J., Brindal, E., James-Martin, G., & Noakes, M. (2018). Randomized trial of a high protein, partial meal replacement program with or without alternate day fasting: Similar effects on weight loss, retention status, nutritional, metabolic, and behavioral outcomes. Nutrients, 10(9), 1145.

Clark, H. W. (2003). Office-based practice and opioid-use disorders. New England Journal of Medicine, 349(10), 928-930.

Filice, M. (February 22, 2017). Sweat lodge. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved online from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sweat-lodge

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). What is land-based treatment and healing? https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-What-is-Land-Based-Treatment-and-Healing.pdf

Garrett, M. T., Torres‐Rivera, E., Brubaker, M., Portman, T. A. A., Brotherton, D., West‐Olatunji, C., Conwill, W., & Grayshield, L. (2011). Crying for a vision: The Native American sweat lodge ceremony as therapeutic intervention. Journal of Counselling and Development, 89(3), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00096.x

Hussain, J., & Cohen, M. (2018). Clinical effects of regular dry sauna bathing: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM, Article 1857413. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1857413

Lavallee, L., & Poole, J. (2010). Beyond recovery: Colonization, health and healing for Indigenous People in Canada. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(2), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9239-8. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227108537_Beyond_Recovery_Colonization_Health_and_Healing_for_Indigenous_People_in_Canada

Leyland, A., Smylie, J., Cole, M., Kitty, D., Crowshoe, L., McKinney, V., Green, M., Funnell, S., Brascoupé, S., Dallaire, J., & Safarov, A. (2016). Health and health care implications of systemic racism on Indigenous Peoples in Canada. College of Family Physicians of Canada. https://portal.cfpc.ca/ResourcesDocs/uploadedFiles/Resources/_PDFs/SystemicRacism_ENG.pdf

Linklater, R. (2014). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Fernwood Publishing.

Marsh, T. N., Marsh, D. C., Ozawagosh, J., & Ozawagosh, F. (2018). The sweat lodge ceremony: A healing intervention for intergenerational trauma and substance use. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9(2). https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/iipj/article/download/7544/6188/

Michalsen, A. (2010). Prolonged fasting as a method of mood enhancement in chronic pain syndromes: a review of clinical evidence and mechanisms. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 14(2), 80–87.

Michalsen, A., Kuhlmann, M. K., Lüdtke, R., Bäcker, M., Langhorst, J., & Dobos, G. J. (2006). Prolonged fasting in patients with chronic pain syndromes leads to late mood-enhancement not related to weight loss and fasting-induced leptin depletion. Nutritional Neuroscience, 9(5–6), 195–200.

Michalsen, A., Weidenhammer, W., Melchart, D., Langhorst, J., Saha, J., & Dobos, G. (2002). Short-term therapeutic fasting in the treatment of chronic pain and fatigue syndromes—Well-being and side effects with and without mineral supplements. Forschende Komplementarmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde [Research in Complementary and Natural Classical Medicine], 9(4), 221–227.

Moran, R. (2020). Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/truth-and-reconciliation-commission

Riley, D., & O’Hare. P. (2002). Harm reduction: Policy and practice. https://canadianharmreduction.com/node/889.

Rowan, M., Poole, N., Shea, B., Gone, J. P., Mykota, D., Farag, M., Hopkins, C., Hall, L., Mushquash, C., & Dell C. (2014). Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: Findings from a scoping study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 9, 34.

Schiff, J. W., & Moore, K. (2006). The impact of the sweat lodge ceremony on dimensions of well-being. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 13(3), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.1303.2006.48. PMID: 17602408.

Sibille, K. T., Bartsch, F., Reddy, D., Fillingim, R. B., & Keil, A. (2016). Increasing neuroplasticity to bolster chronic pain treatment: A role for intermittent fasting and glucose administration? The Journal of Pain, 17(3), 275–281.