Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe the role of motivation in behavioural change.

- Identify motivation and change strategies that are supported by evidence.

- Identify stages of behavioural change.

- Describe self-regulation theory.

- Outline debrief interventions including SBIRT (screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment).

- Discuss how health and social service providers can incorporate motivation and change theories in their practice.

Key Concepts

- The concept of motivation to change behaviour has evolved, and the responsibility for treatment success has shifted from the individual alone to their relationship with health and social service providers.

- Motivation has been described as a prerequisite for treatment, and the therapeutic relationship is a critical component of successful treatment.

- Although change in behaviour is the responsibility of the client, health and social service providers can enhance the individual’s motivation for positive change.

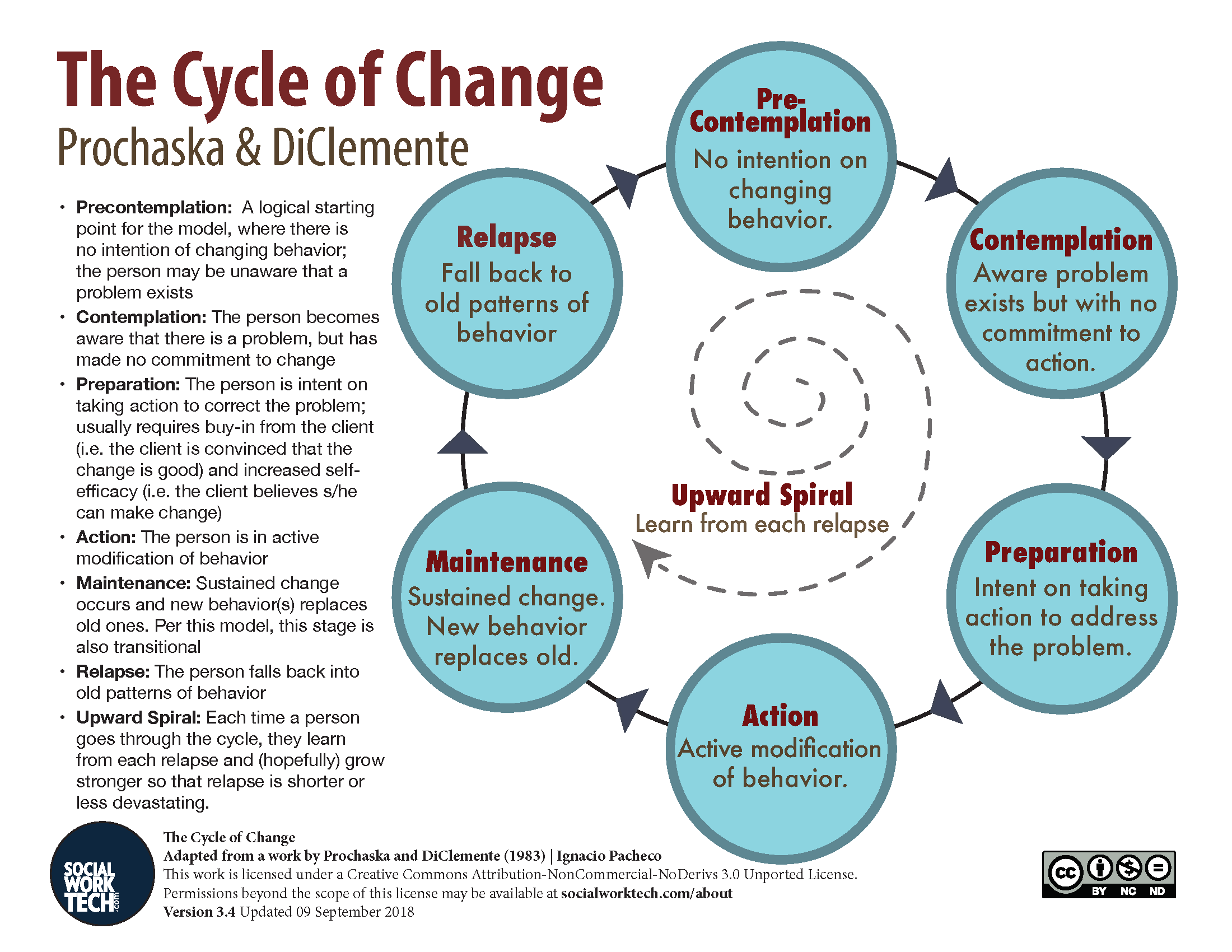

- The stages of change in the transtheoretical model (TTM) developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in 1983 provide a model that explains the change process, including the stage of ambivalence.

Historical View of Motivation

Motivation to change among individuals receiving treatment for substance use disorder has been a focus of concern among service providers.

While motivation is considered to be a prerequisite for treatment, the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (1999) identified an important shift in how it is understood.

- Historically, motivation was believed to be a static internal trait or disposition that a client either did or did not possess, and that service providers could do little about.

- Lack of motivation was frequently used to explain an individual’s inability to begin treatment, continue treatment, or complete a treatment program successfully.

- Motivation for treatment was viewed as the individual’s willingness to go along with a health and social service provider's particular approach to recovery, and therefore a choice. So, a lack of motivation to change was seen as the client’s fault.

- A client who seemed amenable to clinical advice or accepted the label of "substance use disorder" was considered to be motivated, whereas one who resisted the diagnosis or refused to adhere to a prescribed treatment plan was deemed unmotivated.

- Motivation was seen to be the exclusive responsibility of the client, rather than the responsibility of the health and social service provider.

Evolving Understanding of Motivation

The concept of motivation has evolved, as has the view that the responsibility for treatment success lies solely with the individual.

We now know:

- The environment of individuals using substances and their relationship with health and social service providers can influence their decision-making and behavior.

- Current conceptualizations of change motivation related to substance use include the following:

- Motivation is a key to change.

- Motivation is multidimensional.

- Motivation is dynamic and fluctuating.

- Motivation is influenced by social interactions.

- Motivation can be modified.

- Motivation is influenced by the health and social service provider’s style.

The provider’s task is to elicit and enhance motivation.

(Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999, Chapter 1, p. 2)

Motivation to change has come to be understood as intentional and directed to what individuals believe to be in their best interest.

- Motivation affects the probability that a person using substances will seek help, resources, and the support to succeed.

- Motivation is enhanced when health and service providers work with the individual to determine the best strategy for positive change.

Attributes of Motivation

The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (1999) provided the following characteristics of motivation:

Multidimensional and Intersectional

Motivation integrates an individual’s internal urges and desires with social, cultural, spiritual, and financial factors. In combination, these variables influence the individual’s perception of the risks and benefits their behaviours will have.

Dynamic and Fluctuating

Motivation is fluid and changes in different situations and in different cognitive states. It vacillates and can vary in intensity.

Influenced by Social Interactions

While motivation is an internal and individual process, it is affected by the individual’s experiences with others (Miller, 1995). An individual's motivation to change can, therefore, be influenced positively or negatively by social variables, including relationships with family, friends, and peers, as well as past trauma or violence. Access to health care, employment, public perception of substance abuse, stigma, discrimination, and historical trauma can also significantly affect an individual's motivation.

Modifiable

Motivation is “accessible and can be modified or enhanced at many points in the change process which brings hope and optimism for change.” (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999, p. 3). Thus, an individual can be actively engaged in change even when they continue to use substances.

Motivation Is Influenced by the Health and Social Service Provider

The Center for Substance Abuse and Treatment (1999) emphasized the important role of the therapeutic relationship in treatment and highlighted the following research findings:

Client dropout rates for a given treatment modality have been linked to the counsellor providing the treatment rather than to the treatment approach.

Counsellor style influences how a client responds to an intervention and has a greater impact on outcomes than client characteristics.

A respectful and positive alliance with clients and good interpersonal skills are more important than professional training or experience in fostering positive outcomes.

- The most therapeutically helpful attributes for a counsellor include warmth, friendliness, genuineness, respect, affirmation, and empathy.

- The therapeutic principles of empathy, honesty, and acceptance, in Carl Roger’s model of counselling, have gained significance in the field of addiction counselling (White & Miller, 2007).

- This approach has been contrasted with an earlier confrontational and authoritarian counselling style (White & Miller, 2007).

A number of studies have indicated that “high empathy” counsellors or therapists have a greater success rate with clients experiencing addiction than do counsellors who are “low empathy” and use confrontational approaches (Moyers & Miller, 2013).

“Low empathy” among counsellors has been associated with “higher client relapse, weaker therapeutic alliances and less client change” (Moyer & Miller, 2013, p. 878).

Health and Social Service Provider Role Related to Motivation

While many people change substance-using behaviour on their own without therapeutic intervention, the health and social service provider can enhance the individual’s motivation for positive change throughout the change process.

Key aspects of a therapeutic relationship include assisting and encouraging individuals to recognize a problem behaviour. An individual may feel tension and discomfort when their values and beliefs are not reflected in their behaviours. This may lead to changes in behaviour, but it often results in changes in beliefs, such as rationalizations regarding behaviour, or denial of its consequences.

Definition

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Cognitive dissonance occurs when an individual’s behaviours and values do not align or are incongruent (Cooper, 2019).

Working with cognitive dissonance can be an effective approach when counselling an individual using substances.

A wider or distal approach may be adopted by service providers to enhance motivation in which historical, societal, or cultural factors that impinge on an individual’s ability to change are identified and labelled.

- Such an approach involves awareness of, sensitivity to, and respect for the impact that culture, race, gender, colonization, and both historical and current trauma may engender on the individual’s motivation to change.

Self-regulation and Self-efficacy Theory

Definition

- Self-regulation

- Self-regulation is an individual's ability to alter a response or override a thought, a feeling, or an impulse (Chavarria et al., 2012, p. 1).

- Self-regulation plays an important role in an individual’s abstention from substance use.

- Self-regulation in the context of addiction is linked to the concept of abstinence self-efficacy.

Definition

- Self-efficacy

- Self-efficacy, according to Bandura’s social-cognitive theory, is the belief a person has in their ability to achieve a desired outcome (Bandura et al., 1999).

- Self-efficacy affects the amount of energy a person will put into an attempt to change an undesired behaviour, such as opioid use. It has emerged as an important predictor of treatment outcomes related to opioid use (Chavarria et al., p. 2).

- Abstinence self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their ability to abstain from an undesired action, including substance use, especially in situations where they often carrying out this action (Chavarria et al., 2012, p. 2).

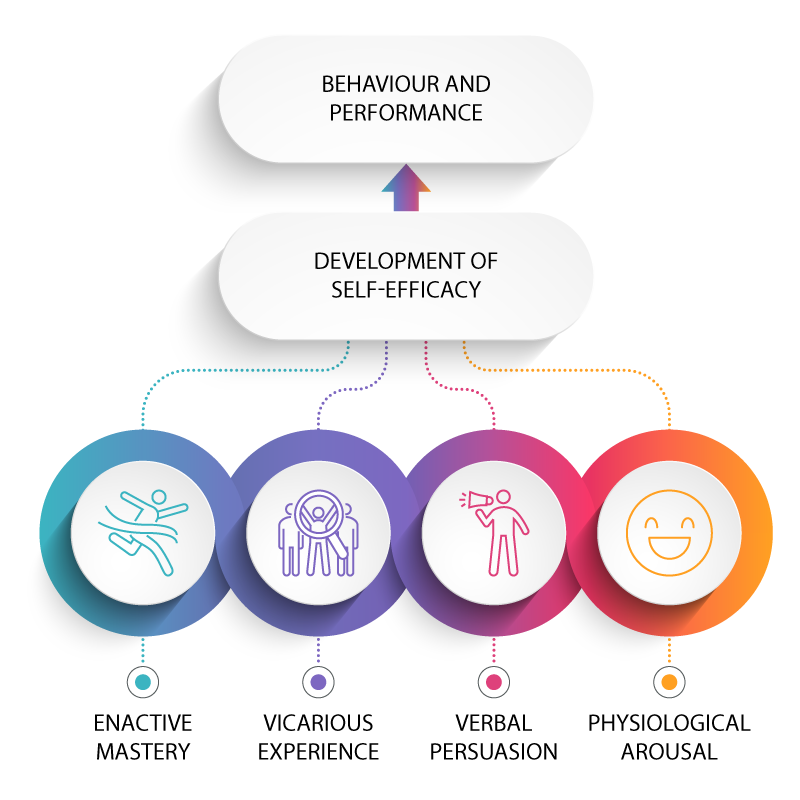

Sources of Self-efficacy

Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy (1999) outlines four sources of self-efficacy:

Enactive Mastery

Bandura refers to occasions in which an individual achieves success as “mastery experiences”. Small achievements enhance feelings of mastery over habits or choices the individual wants to refrain from.

Vicarious Experience

Bandura proposed that watching others, such as peers, achieve success increases people’s belief that they too can succeed. Being in the company of others who have achieved treatment success or managed to refrain from drug use supports an individual belief in their own ability to succeed.

Verbal Persuasion

Verbal encouragement from influential people such as elders, mentors, peers, and counsellors also increase self-efficacy. Telling a person that they have the capacity, the drive, and/or the skills to achieve a goal, such as sobriety, can strengthen their belief that they will be able to achieve this.

Physiological Arousal

Positive emotions, even in the face of stress and anxiety, can increase a person’s belief that a goal can be achieved. Encouraging the use of positive coping strategies to deal with stress, depression, and anxiety can improve a sense of self-efficacy.

(Bandura et al. 1999)

zmicierkavabata/iStock (template); PeterSnow/iStock (icons)

Self-efficacy and Treatment of Substance Use

In examining research on abstinence self-efficacy, Kadden and Litt (2011) concluded that it is an important predictor of treatment outcomes (p. 3). They noted the following findings in this research:

- People who possess confidence in their ability to abstain from substance use and who have strong coping efficacy are likely to mobilize the effort needed to successfully resist situations of high risk for drug use (p. 2).

- When their ability to abstain from substance use slips, highly self-efficacious persons are likely to identify this as a temporary setback and regain self-control, whereas those with low self-efficacy are more likely to continue the substance use (p. 2).

The Stages of Change

The stages of change in the transtheoretical model (TTM), developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983), provide a widely accepted model of the process of change related to substance use. This model identifies six stages in the process that are described below.

Download Accessible Version (PDF)

(Pacheco, 2012)

For most substance-using individuals, progress through the stages of change is circular or spiral in nature, not linear. In this model, relapse is a normal event because many clients cycle through the different stages several times before achieving stable change.

- Movement back and forth, as well as recycling through the stages, represents a successive learning process: the individual continues to redo the tasks of various stages to achieve a level of completion that supports movement toward sustained change of the desired behaviour.

- Motivation is viewed as an important component throughout the entire process of change. The stages of change specify motivational demands by segmenting the change process into specific tasks to be accomplished and goals to be achieved if movement toward successfully sustained change is to occur.

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)

SBIRT is an acronym that stands for screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment that is widely used in a variety of non-substance-abuse treatment settings, including schools, social services, primary care setting, and emergency rooms.

- It is a public health approach to delivering early intervention to people with a substance use disorder or who are at risk of developing such a disorder. SBIRT applies motivational interviewing principles to foster behavioural change.

The components of SBIRT are described as follows (Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, 2007):

- Screening clients quickly for problematic behaviours related to substance use disorder, dangerous use of drugs and alcohol, or the risk of developing dependence. The validated screening tools take about 5 to 10 minutes to administer.

- Brief intervention is given to those with problematic behaviours. The interventions focus on increasing awareness and insight related to substance use and on fostering motivation towards behavioural change. It is generally provided in person in one to five sessions lasting five minutes to an hour and may be based on the FRAMES framework (feedback, responsibility, advice, menu of strategies, empathy, self-efficacy):

- Feedback – Providing constructive feedback on the client’s degree of substance use based on the assessment

- Responsibility – Enabling the client to take personal responsibility for direction and plans

- Advice – Informing and advising the client about substance use respectfully

- Menu of strategies – Collaborating with the client to identify strategies to cut down or stop substance use

- Empathy – Communicating with respect and empathy

- Self‐efficacy – Fostering the client’s sense of self-efficacy

- Referral to treatment is done for those identified as needing more extensive treatment and specialty care. Strong coordination and integration of the components of SBIRT is essential to ensure links between early intervention and more specialized treatment services.

To implement SBIRT, it is critical to have service providers who are trained in its core components of screening, brief intervention, and referral.

Screening Tools and SBIRT Resources

There are a number of screening manuals and tools associated with SBIRT.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) was initially used in the substance use field but has been adapted to a variety of contexts. Motivational interviewing is a brief intervention in the SBIRT model. MI is based on four principles:

- expressing empathy and avoiding arguing

- developing discrepancy (i.e., building the person’s awareness of the gap between current behaviour and a desired outcome)

- rolling with resistance (i.e., recognizing that resistance to change occurs and the client is not ready)

- supporting self-efficacy

The goal of MI is not to direct behaviour, teach a skill, or provide a predetermined piece of information, but rather to explore and reinforce an individual’s motivation. A growing body of literature has measured the efficacy of MI. Most evidence supporting MI, however, is in the field of alcohol use, with limited studies directly looking at MI and opioid use (DiClemente et al, 2017).

Summary of Brief Intervention

For more information, see Clinician Tools.

Population

It has been used in diverse communities among people with problematic substance use.

Gap addressed

It addresses secondary prevention of substance use disorder (early detection and intervention).Core integration/transition strategies

It includes screening and links across various levels of treatment (i.e., brief intervention, brief treatment, and referral to specialized treatment).

Services, sectors, levels of care involved

It is delivered in a wide range of non‐specialized settings (e.g., public health, primary care, emergency and trauma departments, community health clinics, schools).

Resource requirements, feasibility

It requires trained staff (e.g., peer health educators, substance abuse professionals, licensed behavioural health counsellors).

Readiness for implementation

Various materials and training programs are available to support training, implementation, and quality assurance.

Effectiveness evidence

Studies show reduction of at‐risk alcohol use among adults; evidence is growing for reduction of at‐risk drug use among adults. Effectiveness with youth is beginning to be evaluated. Study limitations include selection bias (those who agree to screening).

(Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, 2007)

Questions

References

Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. (2007). The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on emergency department patients’ alcohol use. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 50(6), 699–710. https://www.eenet.ca/sites/default/files/pdfs/SBIRT.pdf

Babor, T. F., McRee, B., Kassebaum, P. A., Grimaldi, P. L., Ahmed, K., & Bray, J. (2007). Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): Toward a public health Approach to the Management of Substance Abuse. Substance Abuse, 28(3), 7–30.

Barnett, E., Sussman, S., Smith, C., Rohrback, L. A., & Spruijt-Metz, D. Motivational interviewing for adolescent substance use: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors, 37(12), 1325–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.001

Chavarria, J., Stevens, E. B., Jason, L. A., & Ferrari, J. R. (2012). The effects of self-regulation and self-efficacy on substance use abstinence. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 30(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2012.718960

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (1999). Conceptualizing motivation and change. In Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 35) (Chapter 1). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64972/

Cooper, J. (2019). Cognitive dissonance: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. International Review of Social Psychology, 32(1), 7. http://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.277

Cognitive dissonance. (2019, April 5). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/cognitive-dissonance

Diclemente, C. C., Corno, C. M., Graydon, M. M., Wiprovnick, A. E., & Knoblach, D. J. (2017). Motivational interviewing, enhancement, and brief interventions over the last decade: A review of reviews of efficacy and effectiveness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31, 862–887.

DiClemente, C., Schlundt, D., & Gemmell, L. (2004). Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. The American Journal on Addictions, 13, 103–119.

Kadden, R. M., & Litt, M. D. (2011). The role of self-efficacy in the treatment of substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 36(12), 1120–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.032

Luborsky, L., McLellan, A. T., Woody, G. E., O'Brien, C. P., & Auerbach, A. (1985). Therapist success and its determinants. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42(6), 602–611.

Madras, B. K., Compton, W. M., Avula, D., Stegbauer, T., Stein, J. B., & Clark, H. W. (2009). Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug use and alcohol use at multiple health care sites: Comparison at intake and six months. Drug Alcohol Dependency, 99(1–3), 280–295.

Majer, J. M., Chapman, H. M., & Jason, L. A. (2016). Abstinence self-efficacy and substance use at 2 years: The moderating effects of residential treatment conditions. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 34(4), 386–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2016.1217708

Miller, W. R., Westerberg, V. S., & Waldron, H.B. (1995). Evaluating alcohol problems. In R. K. Hester & W. R. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: Effective alternatives (2nd ed., pp. 61–88). Allyn & Bacon.

Moyers, T. B., & Miller, W. R. (2013). Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 878–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030274

Pacheco, I. (2012). The stages of change. Retrieved from http://socialworktech.com/2012/01/09/stages-of-change-prochaska-diclemente/?v=f24485ae434a

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of the structure of change. In Self Change (pp. 87–114). Springer.

Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., & Evers, K. E. (2015). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. V. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 125–148). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in behavioral healthcare [White paper]. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sbirtwhitepaper_0.pdf

Whitlock, E. P., Pole, M. R., Green, C. A, Orleans, T., & Klein, J. (2004). Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventative services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 140(7), 557–568.

White, W., & Miller, W. (2007). The use of confrontation in addiction treatment: History, science and time for change. Counselor, 8(4), 12–30.

Young, M. M., Stevens, A., Galipeau, J., Pirie, T., Garritty, C., Singh, K., Yazdi, F., Golfam, M., Pratt, M., Turner, L., Porath‐Waller, A., Arratoon, C., Haley, N., Leslie, K., Reardon, R., Sproule, B., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2014). Effectiveness of brief interventions as part of the screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) model for reducing the non‐medical use of psychoactive substances: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 3, Article 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-50