Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Explain the transtheoretical model (TTM) and stages of behaviour change.

- Recognize when someone is receptive to treatment.

- Summarize the concept of building trust to ensure safety for individuals ready for treatment.

- Describe the characteristics of health and social service providers that support improved treatment outcomes.

Key Concepts

- The transtheoretical model (TTM) describes six stages of changes that an individual may progress through to implement long-term behaviour change.

- Individuals may not necessarily progress through the stages linearly, and often there will be multiple attempts at behaviour change.

- Trust between a person using opioids and the health and social service provider is considered essential to the treatment process.

- Clients must also believe that their healthcare professional has their best interest in mind when reviewing treatment plans.

Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of Change

The transtheoretical model (TTM) describes six stages of change that an individual may progress through to implement long-term behaviour change. These stages describe the “how” of individual behaviour change.

| Stages of Change | Description |

|---|---|

| Precontemplation | No intention to take action within the next 6 months |

| Contemplation | Intends to take action within the next 6 months |

| Preparation | Intends to take action within the next 30 days and has taken some behavioural steps in this direction |

| Action | Changed overt behaviour for less than 6 months |

| Maintenance | Changed overt behaviour for more than 6 months |

| Termination | No temptation to relapse and 100% confidence |

(Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983)

Individuals may not necessarily progress through the stages linearly, and often there will be multiple attempts at behaviour change.

To understand why some individuals fail at behaviour change or why others require multiple attempts, further research has identified an additional 10 processes of change that aim to explain “why” people change.

| Processes of Change | Description |

|---|---|

| Consciousness raising | Increasing awareness about the causes, consequences, and cures for a problem behaviour, e.g., nutrition education |

| Dramatic relief | Increasing negative or positive emotions to motivate taking appropriate action |

| Self-re-evaluation | Cognitive and affective reassessment of one’s self-image, with or without an unhealthy behaviour (values clarification) |

| Environmental re-evaluation | Cognitive and affective reassessment of how the presence or absence of a behaviour affects one’s social environment |

| Self-liberation | Belief that one can change and the commitment and recommitment to act on that belief |

| Helping relationships | Caring, trust, openness, and acceptance as well as support from others for healthy behaviour change |

| Social liberation | Increase in healthy social opportunities or alternatives |

| Counterconditioning | Learning healthier behaviours that can substitute for problem behaviours |

| Stimulus control | Removing cues for unhealthy habits and adding prompts for healthier alternatives |

| Reinforcement management | Rewarding oneself or being rewarded by others for making progress |

(Prochaska et al., 1992)

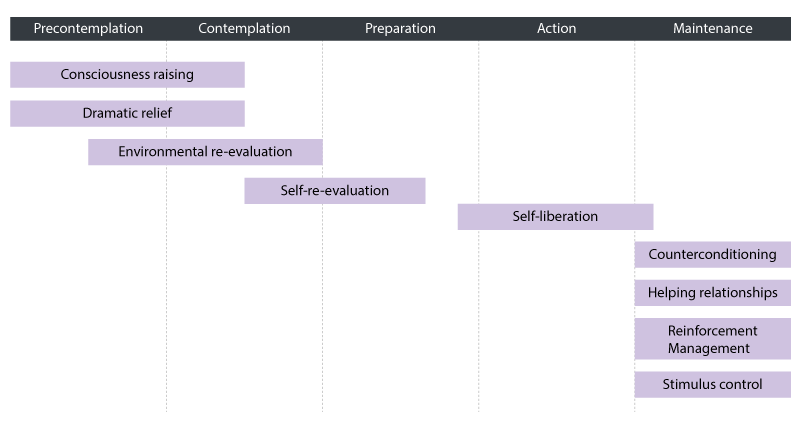

Individuals may use specific processes across each stage of change.

For example, the precontemplation stage may be where consciousness raising occurs (see below).

Consciousness raising and dramatic relief may occur during the precontemplation stage and stretch halfway into the contemplation stage. Environmental re-evaluation may start during the middle of the precontemplation stage and end at the end of the contemplation stage. Self-re-evaluation may start during the middle of the contemplation stage and stretch to the middle of the preparation stage. Self-liberation may start just before the action stage and end just after the action stage. Counterconditioning, helping relationships, reinforcement management and stimulus control may all occur during the maintenance stage.

(Prochaska et al., 1992)

Recognizing When Someone is Ready to Be Receptive to Treatment

The concept of readiness to change (RTC) is commonly used when assessing behavior change (Carey et al., 1999). Currently, no standard measure of RTC is available at the clinical level. Instead, scholars recommend that multiple variables be taken into consideration when determining the RTC: the population, context, and the health condition of the individual.

The TTM provides a sound model to assess RTC. Health and social service providers working with persons using substances can identify their stage of change and the necessary process of change.

- The ideal is for the individual to progress further along each stage to solidify long-term behaviour change.

- Example: A patient with an opioid addiction in the action stage is more likely to stop using

Recommendations to Assess Readiness to Change

Moving from Precontemplation to Contemplation

Prior to engaging in treatment for substance use, certain events must alter an individual’s perceptions to recognize that their current situation is an issue. At precontemplation stage, recognition hasn’t necessarily happened yet. When someone describes their substance use behaviour as an issue, many respond with denial, disbelief, or even hostility.

Clinicians have many opportunities to intervene at this stage to move the client to the next stage. If clinicians offer treatment information in an empathic manner, rather than being judgmental or confrontational, clients may be more receptive to receiving the message and recognizing that there is a problem.

Consider the following recommendations:

- Provide a safe and helpful environment

It is essential that clients not be under the influence of any drugs so that they can provide reliable information. - Raise the topic

It is best practice not to assume that clients are aware of their condition. - Have a short and concise initial conversation

Once the topic is raised, health and social service providers should ask clients why they have an opioid addiction. One strategy is discussing a topic of interest to the client that can be linked to the use of the opioid. It may start by asking if the clients has any stressors such as chronic pain or work stress. This can lead to asking questions like, “How does your use of [the drug] affect your spiritual health?” - Establish rapport and trust

Health and social service providers can talk about what a potential treatment program might look like and how they and the client could work together. - Avoid negative words

Health and social service providers should take care to avoid using negative words such as problem or substance abuse. - Explore events that precipitated treatment entry

The goal of this stage is to understand clients’ readiness to change and the context that brought them to treatment. Ask open-ended questions, listen carefully, summarize, and elicit motivational statements. - Commend clients for attending

Clients referred for treatment have various expectations, ranging from being cured to expecting to be blamed for their addiction. Health and social service providers can use praise, such as "I'm impressed you made the effort to get here," to affirm to clients that they can make decisions in their own best interest.

(Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999a)

Moving from Contemplation to Preparation

Consider the following recommendations:

- General approach

- Ask open-ended questions

- Use reflective listening skills

- Express empathy concerning the client’s predicaments

- Acknowledge and normalize ambivalence

- Show curiosity and maintain attention on clients

- Explore specific pros and cons

It is often helpful to have clients write out the pros and cons on paper. A written list allows clients to better understand the value of changing their behaviour. - Set goals

After clients have made a commitment to change, they should write their goals on paper. Goal setting is crucial for moving to the next stage. According to the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (1999b, p. 91) the paper might include the following:- A summary of the client's own perceptions of the problem, as reflected in self-motivational statements

- A summary of the client's ambivalence, including what remains positive or attractive about the problem behaviour

- A review of whatever objective evidence the health and social service provider has regarding the presence of risks and problems

- A restatement of any indication the client has offered of wanting, intending, or planning to change

- The clinician’s assessment of the client's situation, particularly at points where it converges with the client's own concerns

For further resources on goal setting see Module 4, Topic H.

- Determine clients’ preferences

To understand clients’ preferred treatment plan, the health and social service provider may ask the following open-ended questions:- What do you think you will do?

- What's the next step?

- What do you think has to change?

- What do you think you can change at the moment?

- What are your options?

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999b

Assess Radiness to Change

Before moving on to the next stage transition, assess the clients’ readiness to change. This will allow them to understand what strategies will be most effective. Consider the following recommendations to complete the assessment (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999a).

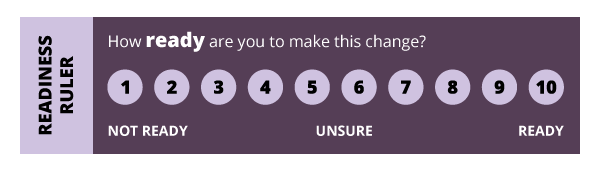

There are two common methods: the readiness ruler and the description of a typical day.

- Readiness ruler

On a readiness ruler, lower numbers represent no thoughts about change and higher numbers represent attempts to change. Clinicians can ask clients questions and have them rate themselves on a scale of 1 to 10, such as:

"How important is it for you to change?"

"How confident are you that you could change if you decided to?"

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

It’s important to realize that these are arbitrary numbers. The goal for a clinician is to facilitate movement in the positive direction. - Description of a typical day

Health and social service providers can use a nonpathological framework to ask clients to describe what a typical day looks like. This approach helps to explain the context of the substance use. The conversation might reveal that the client spends most of his time working and has little time left to spend with family. These conversations help a clinician to understand how the client is using the substance and what challenges there are for giving it up. For some, opioids can mask emotional wounds; for others, they offer excitement.- Ask for a walkthrough.

The health and social service provider might start by ask questions such as, "Can we spend the next few minutes going through a typical day or session of [the drug] use, from beginning to end? Let's start at the beginning." The clinician would ask probing questions to gain a better understanding of the context of when, how, and why the client uses opioid. - Provide information about the effects and risks of substance use.

It’s recommended that health and social service providers offer basic information about the substance use early in the treatment process. Clients can first be asked to explain what they know about the substances they use.

Using motivational language is important when providing education to increase clients’ self-efficacy. The goal is to make clients more aware of the risks related to their substance use so that change becomes an increased possibility.

- Ask for a walkthrough.

Moving from Preparation to Action

At this stage, it’s time to develop a plan for action. By now, clients should have a good understanding of how their substance use affects their lives, and they should recognize the consequences of continued use.

There are several signs of readiness to act (Centre for Interdisciplinary Addiction Research, 2008):

- Decreased resistance. The client stops arguing, interrupting, denying, or objecting.

- Fewer questions about the problem. The client seems to have enough information about their problem and stop asking questions.

- Resolve. Clients appear to have reached a resolution and may be more peaceful, calm, relaxed, unburdened, or settled. Sometimes this happens after a client has passed through a period of anguish or tearfulness.

- Self-motivational statements. Clients make direct self-motivational statements reflecting openness to change ("I have to do something") and optimism ("I'm going to beat this").

- More questions about change. Clients ask what they can do about the problem, how people change once they decide to, and so forth.

- Envisioning. Clients begin to talk about how life might be after a change, to anticipate difficulties if a change were made, or to discuss the advantages of change.

- Experimenting. If clients have had time between sessions, they may have begun experimenting with possible change approaches (e.g., going to an Alcoholics Anonymous [AA] meeting, reading a self-help book, stopping substance use for a few days).

This is the time to customize a plan for change. Creating a plan is the last step in the preparation stage. An actionable plan should have the following items:

- A variety of change options

- A behaviour contract

- Ways to lower barriers to action

- Ways to enlist social support

- Education about treatment

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999c

Moving from Action to Maintenance

The goal of behaviour change long-term maintenance. The following strategies should be recommended to clients to maintain and stabilize recovery.

- Engage in supportive groups.

- Develop coping strategies for temptation.

- If there is a relapse, elicit inner motivations to get back on track.

Common Limitations of the Transtheoretical Model

Even though TTM has proven effective in assessing RTC, it has a number of limitations (Brug et al., 2005).

- People are unpredictable, so it is impossible to categorize people in fixed stages and assume that they will progress linearly. Instead, some might skip stages due to life events. For example, a patient in the precontemplation stage is diagnosed with cancer and might jump from the precontemplation stage to the termination stage. Scholars suggest the use of the term processes instead of stages because addictive behaviour is a continuous process—people change their minds as life moves.

- There is no standard method to categorize individuals into the six stages. In general, algorithms are used. The lack of standard criteria results in different researchers using different sets of criteria; as a result, the validity of these different criteria has not been established.

Certain aspects of the TTM offer valuable insights in developing effective behaviour change strategies, but other strategies/models should be used to complement TTM in implementing behaviour change strategies.

Building Trust to Ensure Safety for Individuals Ready for Treatment

Trust between a client and health and social service provider is essential to the treatment process. Clients must also believe that their health and social service provider has the clients’ best interest or outcome in mind when reviewing treatment plans.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis using 13 randomized controlled trials showed that client-clinician relationships have a statistically significant effect on health care outcomes (Kelley et. al., 2014).

- Another meta-analysis exploring the relationship between trust and health outcomes found a significant small correlation between trust and clients’ health behaviour and found a significant moderate correlation between trust and subjective health-related experiences (Birkhäuer et al., 2017).

- Clients’ trust in health and social service professionals may improve health outcomes through better compliance, more disclosure, and a stronger placebo effect.

- A recent survey of 1588 adults receiving chronic opioid therapy for pain management found that a majority (82.2%) trusted their provider’s judgment (Sherman et al., 2018).

The perception of individuals on chronic opioid therapy as being “drug seekers” can often harm the relationship between health and social service providers and persons who use drugs (PWUD), specifically the mutual trust necessary for better treatment outcomes. This is why it might be even more important for health and social service professionals who are treating PWUD to ensure mutual trust is developed.

PWUD might be hesitant to seek treatment in the first place because of a fear of being stigmatized.

A qualitative study that sought to identify barriers to PWUD found that mistrust, loss of dignity, stigma, and discrimination in health care settings were common factors that prevented treatment-seeking behaviours (Zamudio-Haas et al., 2016)

- The authors identified several outreach strategies to develop trust, including using peer community outreach workers to enroll individuals in treatment plans.

- Specifically for women, developing trust in the service provider was a necessary first step to enroll in treatment plans.

Health and Social Service Provider Characteristics for Better Treatment Outcomes

Personal characteristics make a difference to individuals when facilitating a climate of respect, trust, and collaboration.

In one study, 85 regular daily or almost daily opioid users were asked what characteristics of the staff members they considered to be barriers to treatment. The number one issue identified was concerns about being judged (Deering et al., 2011).

- Clients also stated that providers focused too much on “adherence to ‘rules’ and the results of urine drug testing rather than an understanding of the nature of addiction and wanting to understand clients as individuals.”

- Providers who are perceived as trustworthy, informed, caring, and respectful were associated with higher retention rates in programs.

In their study of 105 individuals in a community-based opioid treatment program, Teruya et al. (2014) found that clients used words such as "nice," "caring," and "respectful" to describe what was particularly impactful in their recovery.

- In addition to personality traits of the health and social service provider, Krahn et al. (2006) found that provider sensitivity to treatment barriers (political, attitudinal, or physical) was equally important when creating individual treatment plans.

Stop and Think

Now that you have reviewed this content, try this:

Using the transtheoretical model, think of barriers that a client might face at each stage of change. How would you address these specific barriers with what you have learned in this topic?

Consider client-centered, practical ways this could be achieved.

Questions

References

Birkhäuer, J., Gaab, J., Kossowsky, J., Hasler, S., Krummenacher, P., Werner, C., & Gerger, H. (2017). Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PloS One, 12(2), e0170988.

Brug, J., Conner, M., Harre, N., Kremers, S., McKellar, S., & Whitelaw, S. (2005). The transtheoretical model and stages of change: A critique: Observations by five commentators on the paper by Adams, J. and White, M. (2004) Why don't stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Education Research, 20(2), 244–258.

Carey, K. B., Purnine, D. M., Maisto, S. A., & Carey, M. P. (1999). Assessing readiness to change substance abuse: A critical review of instruments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6(3), 245–266.

Centre for Interdisciplinary Addiction Research. (2008). Models of good practice in drug treatment in Europe (“Moretreat”): Final report. https://www.zis-hamburg.de/uploads/tx_userzis/Finalrep_moretreat081115.pdf

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (1999a). From precontemplation to contemplation: Building readiness. In Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 35) (Chapter 4). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/tip35_final_508_compliant_-_02252020_0.pdf

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (1999b). From contemplation to preparation: Increasing commitment. In Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 35) (Chapter 5). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/tip35_final_508_compliant_-_02252020_0.pdf

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (1999c). From preparation to action: Getting started. In Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 35) (Chapter 6). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/tip35_final_508_compliant_-_02252020_0.pdf

Deering, D. E., Sheridan, J., Sellman, J. D., Adamson, S. J., Pooley, S., Robertson, R., & Henderson, C. (2011). Consumer and treatment provider perspectives on reducing barriers to opioid substitution treatment and improving treatment attractiveness. Addictive Behaviors, 36(6), 636–642.

Grimley, D., Prochaska, J. O., Velicer, W. F., Blais, L. M., & DiClemente, C. C. (1994). The transtheoretical model of change. Changing the self: Philosophies, techniques, and experiences, 201–227.

Kelley, J. M., Kraft-Todd, G., Schapira, L., Kossowsky, J., & Riess, H. (2014). The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS One, 9(4), e94207.

Lee, Y. Y., & Lin, J. L. (2009). Trust but verify: The interactive effects of trust and autonomy preferences on health outcomes. Health Care Analysis, 17(3), 244–260.

Miller, W. R. (Ed.). (1999). Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment. Diane Publishing.

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of the structure of change. In Self-change (pp. 87–114). Springer.

Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., & Evers, K. E. (2015). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 97.

Sherman, K. J., Walker, R. L., Saunders, K., Shortreed, S. M., Parchman, M., Hansen, R. N., Thakral, M., Ludman, E. J., Dublin, S., & Von Korff, M. (2018). Doctor-patient trust among chronic pain patients on chronic opioid therapy after opioid risk reduction initiatives: a survey. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 31(4), 578–587.

Teruya, C., Schwartz, R. P., Mitchell, S. G., Hasson, A. L., Thomas, C., Buoncristiani, S. H., Hser, Y. I., Wiest, K., Cohen, A. J., Glick, N., Jacobs, P., McLaughlin, P., & Ling, W. (2014). Patient perspectives on buprenorphine/naloxone: a qualitative study of retention during the starting treatment with agonist replacement therapies (START) study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(5), 412–426.

Zamudio-Haas, S., Mahenge, B., Saleem, H., Mbwambo, J., & Lambdin, B. H. (2016). Generating trust: Programmatic strategies to reach women who inject drugs with harm reduction services in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. International Journal of Drug Policy, 30, 43–51.