Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Explain the different stages in the stages of change model.

- Relate the stage to the person’s treatment needs.

- Recognize the importance of language when working with a person in this stage.

Key Concepts

- All stages in the change process are important and are not linear.

- The perspectives of and feelings toward the stages are important for the health and social service provider to recognize and process in order to be helpful.

- The use of change talk questions can be helpful to facilitate clients’ moving to the next stage.

The Stages of Change

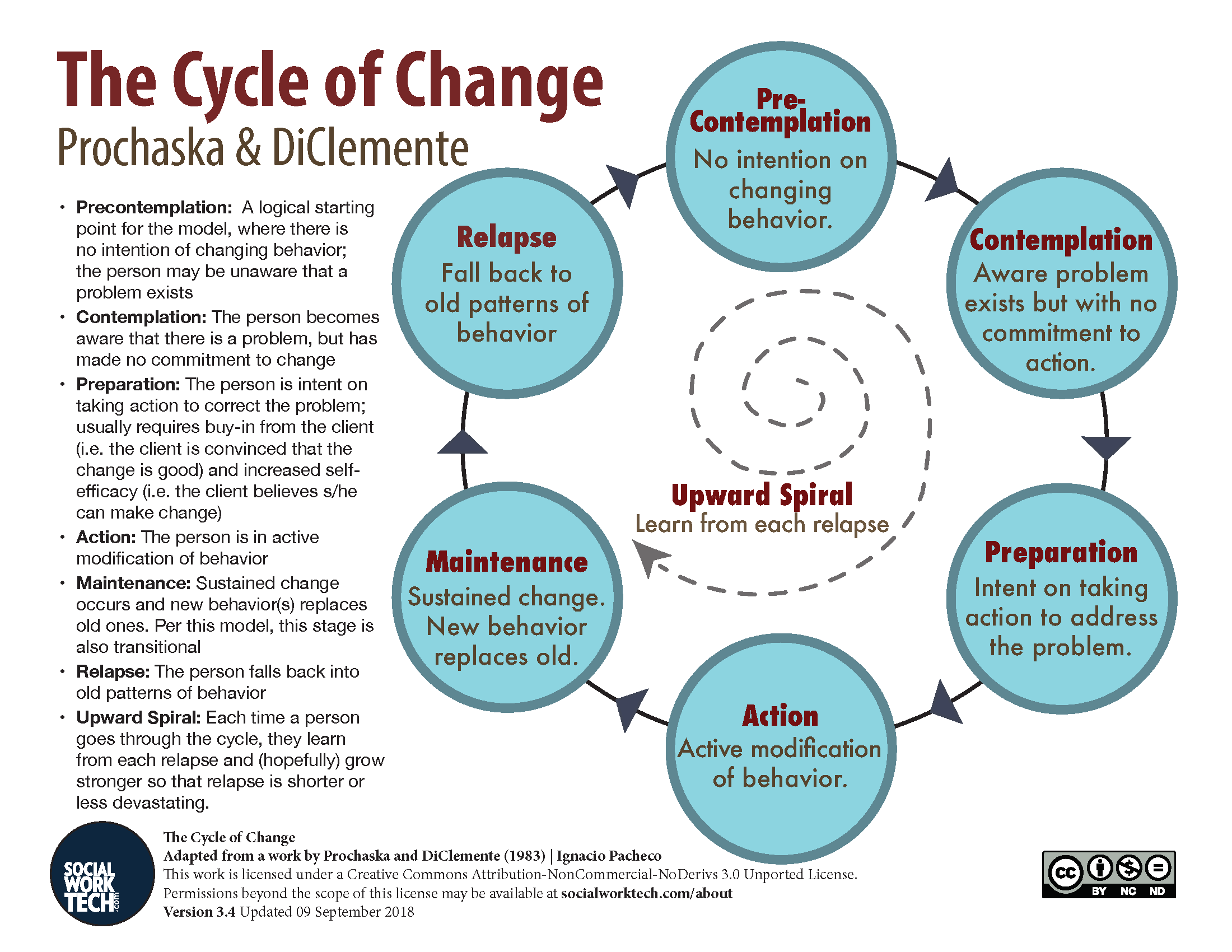

The stages of change in the transtheoretical model (TTM), developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983), provide a widely accepted model of the process of change related to substance use. This model identifies six stages in the process that are described below.

Download Accessible Version (PDF)

(Pacheco, 2012)

For most substance-using individuals, progress through the stages of change is circular or spiral in nature, not linear. In this model, relapse is a normal event because many clients cycle through the different stages several times before achieving stable change.

- Movement back and forth, as well as recycling through the stages, represents a successive learning process: the individual continues to redo the tasks of various stages to achieve a level of completion that supports movement toward sustained change of the desired behaviour.

- Motivation is viewed as an important component throughout the entire process of change. The stages of change specify motivational demands by segmenting the change process into specific tasks to be accomplished and goals to be achieved if movement toward successfully sustained change is to occur.

Prochaska and DiClemente’s model can be applied to substance use treatment. This short video explains the stages of change model as it relates to substance use.

Let’s review an example for each stage and explore the related treatment needs.

| Stage | Example | Treatment Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation. The individual is not considering change, is aware of few negative consequences, and is unlikely to act soon. | A person is considered to be functional despite engaging in substance use/misuse. | This client needs information linking challenges and potential problems with the substance use/misuse. A brief intervention can be done through education on the outcomes of continued use. For example, if the individual is also experiencing depression, a discussion on how opioid use may cause or exacerbate the depression can be helpful. |

| Contemplation. The individual is aware of some pros and cons of substance use/misuse but feels ambivalent about change. This individual has not yet decided to commit to change. | An individual receives a citation for driving while under the influence of opioids promises that next time they will not drive when consuming. They are aware of the consequences but make no commitment to stop using, just to not drive after using. | This client should be supported to explore feelings of ambivalence and the conflicts between their substance use/misuse and personal values. The brief intervention might seek to increase the client's awareness of the consequences of continued use/misuse and the benefits of decreasing as in harm reduction or stopping use. |

| Preparation. This stage begins once the individual has decided to change and begins to plan steps toward recovery. | An individual decides to stop using/misusing substances and plans to attend counselling or a formal treatment program. | This client should be supported to work on strengthening commitment. A brief intervention might give the client a list of options for treatment (e.g., inpatient treatment, outpatient treatment, 12-step meetings) from which to choose, then help the client plan how to go about seeking the treatment that is best for their unique situation and circumstances. |

| Action. The individual tries new behaviours, but these are not yet stable. This stage involves the first active steps toward change. | An individual goes to counselling and attends meetings but often thinks of using again or may even relapse at times. | This client requires help executing an action plan and may have to work on skills to maintain change. The provider should acknowledge the client's feelings and experiences as a normal part of recovery. Brief interventions could be applied throughout this stage to prevent relapse. |

| Maintenance. The individual establishes new behaviours on a long-term basis. | An individual attends counselling regularly, is actively participating in a treatment program, may be taking methadone, and has found a new circle of support. | This client needs help with relapse prevention. A brief intervention could reassure, evaluate present actions, and redefine long-term maintenance plans. |

| Relapse. The individual returns to previous behaviours of use/misuse. | An individual begins to use/misuse again, which usually happens when stress or a negative event occurs, such as a job loss, relationship breakup, illness, or other stressful life event. | The client requires support to evaluate why previously changed behaviours and techniques were inadequate and to learn how to strengthen learned techniques, or learn new ones, as part of moving forward. The provider must do this with empathy and care and without judgement. Relapse can be a one-time lapse or can occur several times (relapse). |

Adapted from Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984

Motivational Interviewing to Support Change

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an empirically based counselling approach in which a health and social service provider uses a collaborative, non-confrontational, and non-judgmental style to resolve clients’ ambivalence to changing their behaviour (Miller & Rollnick, 2012.)

- Clients may provide statements that support change (“It might be time for a change”), as well as statements that oppose change (“I don’t think it’s the right time for a change”) (Osilla et al., 2015).

- Service providers can encourage “change talk” and explore “sustain/status quo talk” by using open-ended questions, reflections, affirmations, and summaries (Miller & Rollnick, 2012).

- When clients express change talk about the target behaviour, it often indicates their readiness to change. Clients who express sustain talk are often more ambivalent about change.

- Client change talk has been posited as an active ingredient of successful MI interventions (Baer et al., 2008; Barnett et al., 2014).

- Because reluctance to change is normal, change talk questions can be helpful in supporting clients through the benefits of and barriers to change, and to work through the ambivalence, which can for several years.

Examples of change talk questions (Zimmerman et al., 2000)

- “Why do you want to change now?”

- “What were the reasons for not changing?”

- “What would keep you from changing now?”

- “What are the barriers today that keep you from change?”

- “What might help you with that aspect?”

- “What things (people, programs, and behaviours) have helped in the past?”

- “What would help you now?”

- “What do you think you need to learn about changing?”

Questions

References

Baer, J. S., Beadnell, B., Garrett, S. B., Hartzler, B., Wells, E. A., & Peterson, P. L. (2008). Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 570–575.

Barnett, E., Moyers, T. B., Sussman, S., Smith, C., Rohrbach, L. A., Sun, P., & Spruijt-Metz, D. (2014). From counselor skill to decreased marijuana use: Does change talk matter? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(4), 498–505.

DiClemente, C., Schlundt, D., & Gemmell, L. (2010). Readiness and stages of change in addiction. In Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 34). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Lindgren, B., Eklund, M., Melin, Y., & Hällgren Graneheim, U. (2015). From resistance to existence—Experiences of medication-assisted treatment as disclosed by people with opioid dependence. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(12), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1074769

Miller, W., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational Interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Osilla, K. C., Ortiz, J. A., Miles, J. N., Pedersen, E. R., Houck, J. M., & D'Amico, E. J. (2015). How group factors affect adolescent change talk and substance use outcomes: Implications for motivational interviewing training. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000049

Pacheco, I. (2012). The stages of change. Retrieved from http://socialworktech.com/2012/01/09/stages-of-change-prochaska-diclemente/?v=f24485ae434a

Rosenblum, A., Magura, S., & Herman, J. (1991). Ambivalence toward methadone treatment among intravenous drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 23(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1991.10472571

Zimmerman, G. L., Olsen, C. G., & Bosworth, M. F. (2000). A stages of change approach to helping patients change behavior. American Family Physician, 1(61), 1409–1416.