Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Differentiate between health inequalities and health inequities.

- Identify the forms health inequalities take as a result of trauma and violence.

- Identify the forms health inequalities take as a result of racism.

- Identify the forms health inequalities take as a result of marginalization.

- Identify the forms health inequalities take as a result of stigma.

- Describe how pervasive these inequalities are in our society.

Key Concepts

- Health inequality and health inequity are separate but interrelated and intertwined concepts.

- Trauma and violence create health inequities that are disproportionate towards, for example, children, women, Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of colour.

- Trauma and violence are embedded in larger structures, such as the health care system, and can reproduce oppressive conditions and experiences of victimization and oppression.

- Stigma is a barrier to seeking help, can influence the quality of care one receives, and can further marginalize certain groups.

- Equity-oriented health care has been shown to improve health outcomes in primary health care.

Difference Between Health Inequality and Health Inequity

Definition

- Health Inequality

- Generically refers to differences in the health of individuals or groups. Any measurable aspect of health that varies across individuals or according to socially relevant groupings can be called a health inequality.

- Health Inequity

- In contrast, a health inequity, or health disparity, is a specific type of health inequality that is systemic and denotes an unjust difference in health. By one common definition, when health differences are preventable and unnecessary, allowing them to persist is unjust.

Health inequities are rooted in social injustices and systemic differences in health that originate from social and economic conditions that disadvantage certain groups more than others and produce differences in health that could be avoided by reasonable means.

NOTE: Health inequities do not occur randomly or by chance. They are socially determined by circumstances largely beyond an individual’s control.

Health equity efforts focus attention on policies that influence health outcomes and the distribution of resources and other processes that are found to drive a particular kind of health inequality—that is, a systematic inequality in health (or in its social determinants) between more and less advantaged social groups.

Health inequity and health inequality are intertwined. Health equity efforts seek social justice in health (i.e., no one is denied the possibility to be healthy because they belong to a group that has historically been economically or socially disadvantaged).

Moving toward greater equity is achieved by selectively improving the health of those who are economically or socially disadvantaged, not by worsening the health of those in advantaged groups.

Health Inequity and Trauma

Childhood

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.) found that adults with higher levels of childhood trauma were more likely to suffer from obesity, smoking, heart disease, alcoholism, depression, and illegal drug use. In fact, those that had childhood trauma were nine times as likely to use drugs.

Take a moment to review the What Are ACEs? (PDF) infographic from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University:

Listen to Dr. Gabor Maté talk about the link between childhood trauma and addiction.

(After Skool, 2021)

Women

A study conducted by the BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (Morrow, 2002) found that health and social service providers, including mental health professionals, downplay the significant role of violence and trauma. As a result, the women involved in the study received inequitable service.

- One of the key findings from this study was that violence and trauma were seen as separate from substance use and mental illness by the health and social service providers.

courtneyk/iStock

Studies have demonstrated strong links between trauma and later substance use, suggesting that women may use substances to self-medicate the psychological symptoms arising from trauma.

Women with histories of repeated abuse are more likely to face homelessness, addiction, and mental illness diagnoses, placing them at further risk for sexual and physical abuse. As a result, homelessness, substance abuse, and mental illness are both outcomes of, and risk factors for future abuse.

The following video describes how the impact of trauma, violence, and abuse impact health (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 2017).

NOTE: Canadian research studies have shown that up to 90 percent of women in treatment for substance use have experienced trauma (Jean Tween Centre, 2013).

Health Inequity and Race

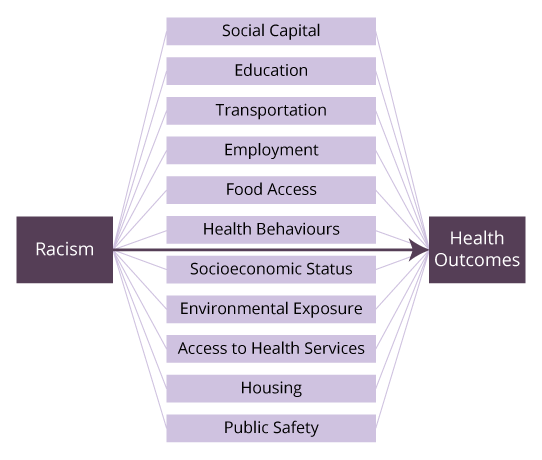

Racism’s influence on social determinants of health - The Boston Public Health Commission's framework for understanding health inequities

Racism influences health outcomes directly while also having an impact on all the social determinants of health: social capital, education, transportation, employment, food access, health behaviours, socioeconomic status, environmental exposure, access to health services, housing, and public safety.

Adapted from Boston Public Health Commission. (2020). Racial justice and health equity. [Online Image]. Boston Public Health Commission. https://www.bphc.org/whatwedo/racialjusticeandhealthequity/Pages/Racial-Justice-and-Health-Equity-Framework.aspx

As shown above, racism has an independent influence on all the social determinants of health and that racism in and of itself has a harmful impact on health. When examining how the factors shown in the image contribute to health inequities, it is important to understand how experiences within the individual and community context differ by race.

Alessandro Biascioli/iStock

Social inequities, such as poverty, segregation, and lack of educational and employment opportunities, have origins in discriminatory laws, policies, and practices that have historically denied people of colour the right to earn income, own property, and accumulate wealth.

Studies have repeatedly shown that racially and culturally diverse groups are often less satisfied with the quality of care that they receive or are hesitant to access health services. This results in the under-diagnosis of illness, a lack of health care, and poor health outcomes.

A Canadian study (Across Boundaries, 1997) suggested that many racialized individuals do not access health services because they are wary of receiving services that operate within a Euro-Western framework, which they perceive as culturally at odds with their values, traditions, and practices.

“The route to achieving equity will not be accomplished through treating everyone equally. It will be achieved by treating everyone justly according to their circumstances.”

Equity-Oriented Health Care

Equity-oriented approaches can be implemented at multiple levels, including within health services, and have been shown, through prior and ongoing research in primary health care (e.g., Browne et al., 2015; Wallace et al., 2018), to be related to key health outcomes, including better quality of life, less chronic pain, and fewer depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms over time.

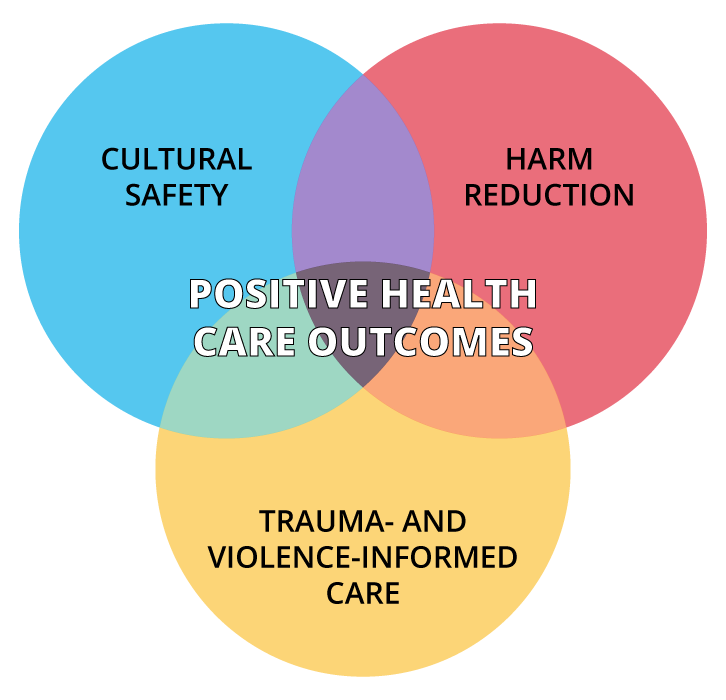

Equity-oriented approaches comprising three intersecting key dimensions—cultural safety, trauma- and violence-informed care, and harm reduction—have demonstrated positive outcomes.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Health Inequity and Marginalization

Definition

- Marginalization

- The process of peripheralizing groups or individuals based on their identities, associations, experiences, environment, or other characteristics.

ismagilov/iStock

Being a member of a marginalized group results in barriers to mainstream society, which is pervasive in all facets of life, including health outcomes. Ultimately, marginalization is a sociological process in which groups are rejected from society, which affects all domains of livelihood.

These barriers present as systematic or structural processes where marginalized peoples are pushed away from economic, sociopolitical, and (dominant) cultural participation. As a result, marginalized groups are placed in a disadvantaged and exclusionary position in society. Rejection from society is accomplished through various ideologies such as:

- racism

- classism

- colonialism

These ideologies are perpetuated by implicit bias and stigmatization often embedded within systems and policies.

The effects of marginalization are widespread, which ultimately result in increased vulnerability for marginalized peoples. Effects include:

- residential segregation

- mass incarceration

- inequities in pay rates and unemployment rates

- lack of access to social and health services

Marginalization and the resultant exclusion from society contributes to poor health outcomes through several mechanisms:

- The systemic effects of lower access to employment, lack of equitable pay, limited access to health services, and poorer physical location contribute to poor access to health care yet increase vulnerability to morbidity and disease.

- Stigmatization of marginalized individuals affects the quality of care they receive.

- Marginalization puts individuals in a poor social position where they are most at risk for poor health outcomes and also the least equipped to address these outcomes.

These poor health outcomes result in marked inequities between marginalized groups and the dominant population.

- For example, in the United States, non-Hispanic Black people have the highest rate of cardiovascular disease mortality despite being a small proportion of the population.

- South Asian Canadians are 2.3 times as likely as White Canadians to have diabetes.

- Canadian women have a 50 percent higher prevalence of arthritis than Canadian men.

NOTE: The risk of poorer health outcomes and drug use increases as the number of intersecting marginalized identities increase.

Inequalities, Marginalization and Indigenous Peoples of Canada

Research clearly indicates a link between the social inequalities created by colonialism and neocolonialism and the later onset of disease, disability, violence, and early death experienced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Colonialism and neocolonialism impact the health of Indigenous peoples by producing social, political, and economic inequalities that trickle down to the infrastructure of how health and social services are delivered.

The result is the social construction of a category experienced by Indigenous people who are now marginalized from their own culture while remaining on the outside of the dominant one. Research is now establishing that such marginalization and social exclusion have even more negative health outcomes because of the stress of living in racialized and oppressive environments.

- As an example, studies with Indigenous youth have shown a link between increased alcohol and drug use and the feeling of being socially excluded.

To learn how the impact of structural violence impacts the health of Indigenous Peoples, watch this video on Indigenous health in Canada from Demystifying Medicine at McMaster University.

Health Inequity and Stigma

Stigma is a major social determinant of population health and has been highlighted as a fundamental cause of health inequalities. Stigma begins with the labelling of differences and negative stereotyping of people, creating a separation between "us" and "them." Those who are stigmatized are devalued and subjected to discrimination, which is unjust treatment. This can lead to disadvantage and inequitable social and health outcomes. Stigma happens:

- in institutions (e.g., health care organizations),

- at a population level (e.g., norms and values),

- through interpersonal relationships (e.g., mistreatment), and

- internally (e.g., self-worth and value).

Stigma can target different identities, characteristics, behaviours, practices, or health conditions. For example, stigma can be based on:

- race,

- gender and gender identity,

- sexual orientation,

- language,

- age,

- substance use,

- ability, and

- social class.

Research covering a range of stigmatized identities has found experiences of stigma predict relatively poor physical health (e.g., risk factors for cardiovascular disease, various physical conditions, self-reported health), as well as both positive (e.g., self-esteem, life satisfaction, well-being) and negative (e.g., depression, anxiety, negative affect) mental health outcomes.

The impacts of stigma on health are exacerbated by a range of psychosocial processes, including depleted personal and material resources, increased stress, and maladaptive forms of emotion regulation and coping behaviours, including substance use.

Stigma related to health conditions can result in:

- obesity,

- substance use disorders,

- mental illness,

- dementia,

- tuberculosis, and

- HIV infection.

When stigmas intersect, they can amplify negative health outcomes.

Stigma is Structural

Stigma can benefit those in power in several ways:

- By keeping people "in," that is, by enforcing preferred social norms and values

- By keeping people "down," which maintains one's group advantage in society

- By keeping people "away," in order to avoid disease or a perceived threat

Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019

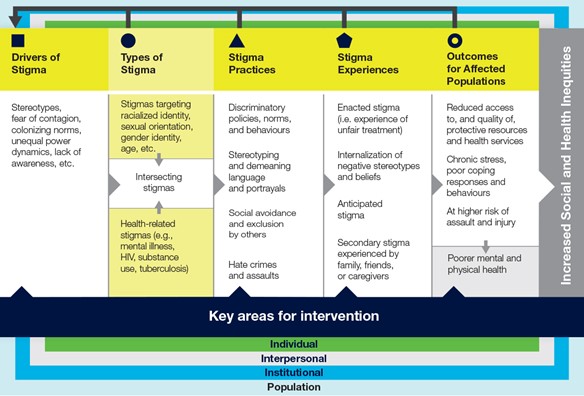

The Stigma Pathways to Health Outcomes Model below highlights the root causes of stigma, the different forms stigma assumes, and how it perpetuates the inequities it creates among Canadians.

The model was designed to accommodate the lens of intersectionality as a comprehensive way to look at stigma. The goal of the model is to identify and highlight how stigma is perpetuated by unequal distribution of power, health inequity, the impact of colonization among other social and cultural influences. A key point of the model is that stigma is fluid. It intersects and transcends the individual experience to that of communities, institutions, systems and society. It is important to look at stigma this way to avoid missing the nuanced ways in which stigma occurs to certain groups in society.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Addressing stigma: Towards a more inclusive health system. The chief public health officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada, 2019. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/addressing-stigma-what-we-heard/stigma-eng.pdf

The Stigma Pathways to Health Outcomes Model works from left (drivers of stigma) to right (outcomes for affected populations). Each section (for example, drivers of stigma) informs the next component to illustrate how stigma is layered and multi-dimensional and intersecting. The researchers who developed the model explain that “applying the model to a particular stigma offers a way to understand how certain drivers lead to the marking and labelling of targeted groups. Once marked, people are then vulnerable to a variety of stigmatizing practices and discriminatory actions from other people, institutions, and society in general. Experiencing stigma can then lead to adverse health outcomes for individuals and increased inequities for populations” (Stangl et al, 2019).

Questions

References

Across Boundaries. (1997). A guide to anti-racism organizational change in the health and mental health sector.

After Skool (2021, Jan 19). How Childhood Trauma Leads to Addiction – Gabor Maté. YouTube. https://youtu.be/BVg2bfqblGI

Boston Public Health Commission. (2020). Racial justice and health equity. https://www.bphc.org/whatwedo/racialjusticeandhealthequity/Pages/rjhe-home.aspx

Braveman, P. (2014). What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl. 2), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S203

Browne, A., Varcoe, C. M., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, N., & Equip Research Team. (2015). EQUIP health care: A multi-component Intervention to enhance equity in primary health care settings. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0271-y

Browne, A., Varcoe, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, N. C., Smye, V., Jackson, B., Wallace, B., Pauly, B., Herbert, C., Wong, S., & Blanchet-Garneau, A. (2018). Disruption as opportunity: Impacts of an organizational-level health equity intervention in primary care clinics. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17, 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0820-2

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About the CDC-Kaiser Permanente adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

Eby, D. K. (2018). Customer-ownership in equity-oriented health care. Milbank Quarterly, 96. https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/customer-ownership-in-equity-oriented-health-care/

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, N., Varcoe, C. M., Herbert, C., Jackson, B., Lavoie, J., Pauly, B., Perrin, N., Smye, V., Wallace, B., Wong, S., Browne, A. J., & EQUIP Research Team. (2018). How equity-oriented health care impacts health: Key mechanisms and implications for primary care practice and policy. Milbank Quarterly, 96(4), 635–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12349.

Inglis, G., McHardy, F., Sosu, E., McAteer, J., & Biggs, H. (2019). Health inequality implications from a qualitative study of experiences of poverty stigma in Scotland. Social Science & Medicine, 232, 43–49.

Jean Tweed Centre. (2013). Trauma matters: Guidelines for trauma-informed practices in women’s substance use services. http://jeantweed.com/wp-content/themes/JTC/pdfs/Trauma%20Matters%20online%20version%20August%202013.pdf

Mereish, E. H., & Bradford, J. B. (2014). Intersecting identities and substance use problems: Sexual orientation, gender, race, and lifetime substance use problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(1), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.179

Milken Institute School of Public Health. (2020). What’s the difference between health equity and health equality? George Washington University. https://publichealthonline.gwu.edu/blog/equity-vs-equality/

Mikhail, J., Nemeth, L., Mueller, M., Pope, C., NeSmith, E. (2018). The social determinants of trauma: A trauma disparities scoping review and framework. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 25(5), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000388

Morrow, M. (2002). Violence and trauma in the lives of women with serious mental illness: Current practices in service provisions in British Columbia. BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. https://bccewh.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/2002_Violence-and-Trauma-in-the-Lives-of-Women-with-Mental-Illness.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Addressing stigma: Toward a more inclusive health system—The chief public health officer's report on the state of public health in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/addressing-stigma-toward-more-inclusive-health-system.html

Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequities and social determinants of Aboriginal Peoples health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-HealthInequalities-Reading-Wien-EN.pdf

Stangl, A.L., Earnshaw, V.A., Logie, C.H. Brakel, W., Simbayi, L.C. et al. (2019). The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine, 17(31) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3

Wyatt, R., Laderman, M., Botwinick, L., & Mate, K. (2016). Achieving health equity: A guide for health care organizations [White paper]. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Achieving-Health-Equity.aspx