Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Identify the ways in which trauma and violence shape poor health such as chronic pain, mental health, and unhealthy coping.

- Recognize the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and the development of unhealthy coping strategies.

- Explain how assessment can detect the association between trauma and violence and these health outcomes.

Key Concepts

- Social and environmental experiences early in life have lasting influences that continue into adulthood.

- Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) can have lifelong consequences and impacts across the life cycle.

- Trauma violence, the intentional use of force to inflict harm on another person, is now understood as a social determinant of health (Morris, 2016; World Health Organization, 2013) across the life cycle.

- Traumatic experiences are associated with both behavioural health and chronic physical health conditions, especially those traumatic events that occur during childhood. Substance use (e.g., smoking, excessive alcohol use, and taking drugs), mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, or PTSD), and other risky behaviours (e.g., self-injury) have been linked with traumatic experiences.

- The colonization and forced assimilation of Indigenous Peoples is considered a root cause of the elevated levels of mental distress.

- Trauma and violence at the societal or structural level inform personal experience, resulting in depression, chronic pain, and use of substances as a way of coping.

- Racial profiling by some health and social service providers can result in trauma and further stigmatization and become a barrier to effective treatment of chronic pain.

- Chronic stress as a result of structural violence such as oppression can be intergenerational, highlighting the importance of understanding the historical context of a person’s narrative/story.

Early Life Adversity and Stress

kieferpix/iStock

Research into early life adversity, also known as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), identify early experiences of stressful or traumatic experiences as strong precursors and predictors of negative outcomes later in life. ACEs are defined as experiences that include abuse, neglect or household dysfunction.

Examples of abuse

- physical

- emotional

- sexual abuse

Examples of neglect

- physical

- emotional

Examples of household dysfunction

- having an incarcerated parent

- witnessing domestic violence

- growing up with substance use, mental illness, parental discord, or crime in the home

Anthony Boulton/iStock

It is the prevalence and cumulative experiences of ACEs that result in high levels of chronic stress that, in the absence of protective relationships, become toxic and harmful.

While ACEs pertain to experiences at the individual level, traumatic environments at the community level also contribute to toxic stress. For example, high crime neighbourhoods where gun violence and drug activity are prevalent are significant sources of toxic stress.

Brian Hartnett Photography/iStock

Research findings link exposure to early traumatic experiences to problems people have developing healthy coping mechanisms later in life. Exposure to trauma and violence is directly correlated with altered neural development and impaired learning, as well as impaired coping mechanisms.

Relationship to Mental Health

In addition to the effects on learning and development, exposure to trauma has been linked to mental health issues that negatively impact emotional wellbeing and behaviour. Research reveals that prolonged exposure to adverse childhood experiences is a strong contributor to:

- depression,

- anxiety,

- posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),

- substance abuse,

- sleep disturbance, and

- suicidal ideation.

These mental health issues can manifest as an impaired ability to regulate behaviours and in the adoption of negative coping mechanisms, such as self-harming and taking substances.

“Repeated trauma can lead to anger, despair, and severe psychic numbing, resulting in major changes in personality and behavior.”

Trauma, Violence, and Chronic Pain

fizkes/iStock

Studies show an association between exposure to violence and an elevated risk of developing conditions involving pain.

Usually, pain is regarded as chronic when it lasts or recurs for more than three to six months. Chronic pain is a frequent condition, affecting an estimated 20 percent of people worldwide.

In a cross-national survey of adults from 14 countries, lifetime exposure to traumatic events, many of which involved violence, was associated with elevated odds of developing adult chronic physical conditions including chronic pain, heart disease, hypertension, asthma, and gastrointestinal conditions.

In this study, the most common chronic pain conditions listed as a result of trauma and violence included:

- frequent and severe headaches (26.8 percent),

- back and neck problems (11.8 percent),

- other chronic pain (6.0 percent), and

- arthritis (2.1 percent).

All pain conditions were more common among females than males.

Racial Bias in Pain Management

A 2016 study identified racial bias toward chronic pain management in Black people. The study revealed that white laypeople, medical students, and residents held false beliefs about biological differences between Black and White people and that these beliefs predicted racial bias in pain perception and treatment recommendation accuracy.

Pain Management in Indigenous Peoples

To understand the contextual factors that inform the concept of pain for Indigenous Peoples, listen to the Pain Management in Indigenous People: Through the Lens of Culture, Society and Medicine webinar in which Dr. J. Bertram discusses the dynamic between pain, trauma, and cultural adaptation in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities.

Bertram (2017) explores influences on pain management, the opioid crisis, and the understanding of the brain, and makes inferences as to how these elements can effectively manage chronic pain in the Indigenous individual and as a population phenomenon.

Trauma, Violence, and Mental Health

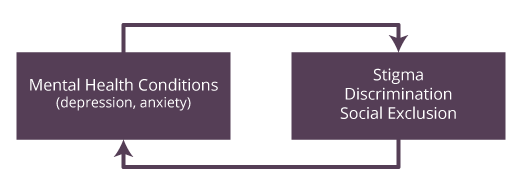

There is a mutual relationship between experiencing mental health conditions (such as depression and anxiety) and experiencing stigma, discrimination, and social exclusion. Likewise, stigma, discrimination, and social exclusion can be factors in the development of depression and anxiety.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

With growing evidence that discrimination and stigma are positively associated with adverse mental health outcomes among ethnic minority groups, ethnic discrimination is now considered a chronic stressor.

- Research indicates that, compared to non-Indigenous individuals, depression rates are higher for both Indigenous men and women residing either on or off a reserve.

- Data collected for the First Nations Regional Health Survey found that 26 percent of men and 35 percent of women living on a reserve felt depressed (First Nations Information Governance Centre, 2012).

- An examination of race, ethnicity, and depression in Canada found that Indigenous groups reported higher levels of depression symptoms and more episodes of major depression compared to Caucasian Canadians.

NOTE: Statistics related to Indigenous health need to be understood as variable; the impact of colonialism, neocolonialism, racism, and so on, has not been the same for all Indigenous Peoples or communities. Health and well-being have been shown to be associated with variation in acculturation histories, geography, protective factors, and so on (e.g., MacDonald et al., 2013, Napoleon, 2009).

Trauma, Violence, and Unhealthy Coping

It is commonly accepted that substances and substance use are a survival strategy for coping and mediating painful feelings.

Chronic stress as a result of victimization caused by colonization, war, family dysfunction, and abuse, among other reasons, can change an individual’s response mechanism to pain and painful feelings.

- The cellular and biochemical changes associated with stress may increase an individual’s post-stress susceptibility to substance use.

- Stress can change the microstructure of the brain in a way that predisposes a person to harmful drug use.

It is important to remember that the relationship between the individual and their environment can influence how the brain responds to long periods of stress by changing the cell structures within the brain.

Please take the time to review the article Interpersonal Violence in the Context of Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use Disorder (Flanagan & Jarnecke, 2020) to view 2020 findings and statistics on this topic.

Questions

References

Bellamy, S., & Hardy, C. (2015). Understanding depression in Aboriginal communities and families. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

Bertram, J. (2017). Pain management in Indigenous people: Through the lens of culture, society and medicine [Video]. Pain BC Society. https://www.painbc.ca/health-professionals/webinars/pain-management-indigenous-people-through-lens-culture-society-and-0

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), 4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113

Ikram, U. Z., Snijder, M. B., de Wit, M. A., Schene, A. H., Stronks, K., & Kunst, A. E. (2016). Perceived ethnic discrimination and depressive symptoms: The buffering effects of ethnic identity, religion and ethnic social network. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(5), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1186-7

Lynn-Whaley, J., & Sugarmann, J. (2017). The relationship between community violence and trauma: How violence affects learning, health, and behavior. Violence Policy Centre. https://vpc.org/studies/trauma17.pdf

First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2012). First Nations regional health survey 2008/10: National report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities.

Flanagan, J., & Jarnecke, A. (2020). Interpersonal violence in the context of posttraumatic stress and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Times, 37(4). https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/depression/interpersonal-violence-context-posttraumatic-stress-and-substance-use-disorders

MacDonald, J. P., Ford, J. D., Willox, A. C., & Ross, N. A. (2013). A review of protective factors and causal mechanisms that enhance the mental health of Indigenous circumpolar youth. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21775

McLaughlin, K. A., Basu, A., Walsh, K., Slopen, N., Sumner, J. A., Koenen, K. C., & Keyes, K. M. (2016). Childhood exposure to violence and chronic physical conditions in a national sample of US adolescents. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(9), 1072–1083. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000366

Moawad, H. (2019). Stress and drug abuse: A structural and genetic link. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/substance-use-disorder/stress-and-drug-abuse-structural-and-genetic-link

Morris, M. (2016). Acting on violence against women is a blueprint for health: A blueprint for Canada’s National Action Plan on violence against women and girls on the health of Canadians through the lens of the social determinants of health. Canadian Network of Women’s Shelters and Transition Houses and the YWCA Canada. https://endvaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Blueprint-and-the-social-determinants-of-health-May-10-2016.pdf

Napoleon, A. (2009). Language and culture as protective factors for at-risk communities. Journal of Aboriginal Health. http://www.ecdip.org/docs/pdf/McIvor_Napoleon%202009.pdf

Treede, R. D., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M. I., Benoliel, R., Wang, S. J. (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156(6), 1003–1007. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence.