Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe the mechanism of opioid-induced respiratory depression

- Describe the signs and symptoms of opioid overdose

- Discuss the mechanism of action of naloxone

- Identify the contents of a naloxone kit

- Instruct others on the administration of naloxone

- Stress the importance of calling 911 for all suspected opioid overdoses

- Describe the “Good Samaritan” law in the context of opioid overdose

Key Concepts

- Opioids exert several effects on the body. At high concentrations, opioids disrupt the respiratory centre in the brain, slow breathing, and reduce the sensitivity of the respiratory centre to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide levels

- A victim of an opioid overdose may have shallow, laboured breathing, or may not be breathing at all, may be unresponsive to verbal or physical stimuli, and will have small, pinpoint pupils

- Naloxone is an opioid receptor antagonist or blocker. When an opioid is over-activating opioid receptors and causing respiratory depression, naloxone will compete with that opioid for receptor binding and “kick off” the opioid from the receptor, to reverse the overdose

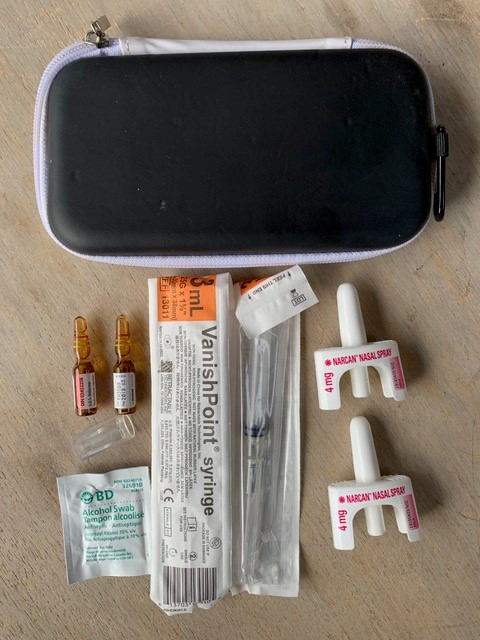

- A typical naloxone kit may contain, sterile gloves, two or more doses of naloxone, either an intramuscular form for injection into the arm or leg, or an intranasal form that is sprayed into a nostril. Often an instruction card, alcohol wipes, and a rescue breathing barrier are included

- Naloxone is a short-acting drug and its effects may not last as long as many opioids. It is crucial to call 911 even if naloxone appears to reverse the overdose, because its effects may wear off

- One barrier to calling 911 is a fear of consequences from law enforcement. The Good Samaritan legislation provides protection to those present at the overdose location, should they be in possession of drugs or drug parephenalia

- An opioid overdose is a medical emergency, and regardless of the outcome, administering naloxone, calling 911, providing CPR, or being a bystander to the event may be very stressful and difficult

Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression (OIRD) AKA Opioid Overdose

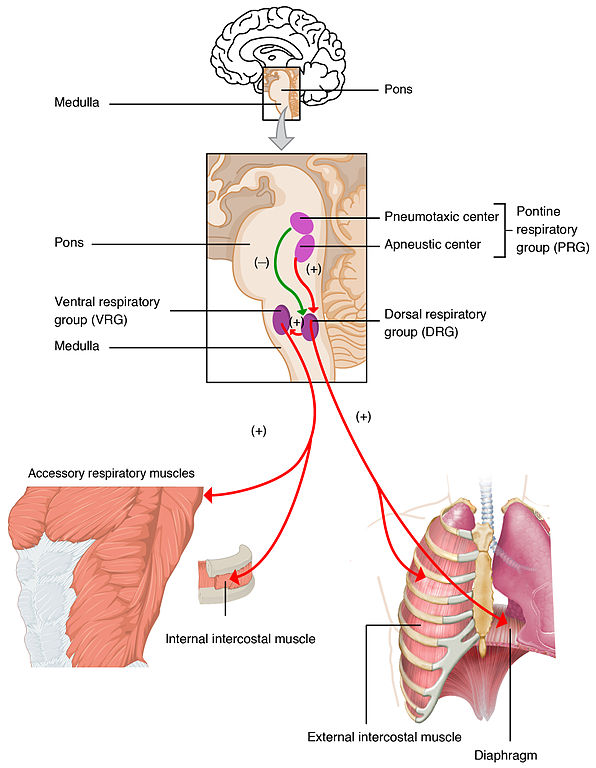

- Opioids activate opioid receptors, μ, delta, and kappa, κ, throughout the body

- In the respiratory centre (a collection of brain nuclei in the brainstem), μ opioid receptors play a key role in regulating breathing

- As the concentration of opioids in the brain increases, the function of the respiratory centre is disrupted, reducing its sensitivity to changes in pH, carbon dioxide, and oxygen

- Normally, as breathing slows, carbon dioxide levels rise, and oxygen levels fall, the respiratory centre increases respiration without conscious control

- In the presence of opioids, respiratory centre function is disrupted, and despite a reduction in breathing, the respiratory centre is “turned off” and cannot reverse the respiratory depression

- Breathing continues to become more shallow, less frequent, and may eventually stop

- Factors that increase the risk of an opioid overdose include: the dose of the opioid, the potency of the opioid, the presence of additional CNS depressions (e.g. alcohol, benzodiazepines), pre-existing cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, obstructive sleep apnea, or any other factor that may impair breathing

Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction and licensed under (CC BY 4.0).

Signs and Symptoms of OIRD

Signs and symptoms of OIRD include:

Slow, shallow, or no breathing

Miosis (pinpoint pupils)

Blue lips, fingernails, skin

Cold, clammy skin

Limp body/arms and legs

No response to shouting or shaking

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Naloxone

University of Waterloo - Faculty of Science, School of Pharmacy. (2016). Naloxone. YouTube. https://youtu.be/BpofNjyaF1w

Used with permission of University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy ©Pharmacy5in5.com

- Naloxone is an opioid receptor antagonist, i.e. blocker

- Naloxone competes with opioids (agonists) for binding to opioid receptors, including µ opioid receptors in the respiratory centre

- In OIRD, naloxone reverse the effects of the opioid at the respiratory centre, restoring normal physiological function/breathing

- Naloxone also reverses other effects of opioids, including the effects of opioids on pain and euphoria, and administration can also result in shivering, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea

- In opioid-dependent individuals, naloxone may precipitate withdrawal symptoms.

Fvasconcellos. (2008). Naloxone [Image]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Naloxone.svg.

Naloxone Infographic (PDF)

University of Waterloo, Faculty of Science, School of Pharmacy (2016). Naloxone. Retrieved online from: https://uwaterloo.ca/pharmacy/sites/ca.pharmacy/files/uploads/files/naloxone_infographic_accessible.pdf Reproduced with permission of University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy ©Pharmacy5in5.com

Naloxone Kits

© Michael Beazely

Naloxone kits typically include:

- A hard case

- Two or more doses of naloxone

- Narcan® Nasal Spray (4 mg nalaoxone /0.1 mL) OR

- 1 mL ampoules or vials of naloxone hydrochloride 0.4 mg/mL intramuscular injection

- Rescue breathing barrier

- Pair of non-latex gloves

- Training card and/or instructional insert

- Alcohol swaps (for injectable naloxone)

- Two safety syringes, 25g, 1 inch needle (for injectable naloxone)

- Ampoule opening device (for injectable naloxone)

Depending on the jurisdiction, naloxone kits can be obtained (free of charge, often without a health card) from pharmacies, public health units, overdose prevention sites and other outreach services.

If a pharmacy doesn’t advertise, offer, or stock naloxone—ASK! One reason that pharmacies may not stock naloxone kits is that they don’t believe their patients and customers are interested in obtaining a kit.

Naloxone Administration

- Intramuscular (IM) naloxone can be injected into a large muscle (shoulder, leg)

- Intranasal naloxone (IN) is sprayed into a nostril

- If there is no effect (no change in breathing, responsiveness) a second dose or additional doses may be administered

- It is not possible to give too much naloxone.

- When an overdose is suspected but not certain, naloxone should be given anyway.

- 9-1-1 should always be called, even if the overdose is successfully reversed with naloxone. The effects of naloxone can wear off more quickly than the effects of many opioids.

How to Administer Intranasal Naloxone:

How to Administer Intramuscular Naloxone:

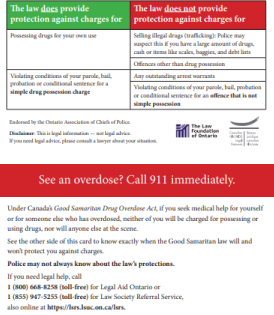

Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act of Canada

- Fear of law enforcement can be a barrier to calling 911 in an opioid overdose, particularly if illicit drugs or drug parephenalia are present

- The Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act protects individuals at the scene of an opioid overdose from charges for possession of a controlled substance, breach of conditions related to drug charges, including pre-trial release, probation orders, conditional sentences, and parole violations

- The Act does not provide protections for outstanding warrants, drug trafficking, or other crimes

Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act Poster (PDF)

Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act: poster. (2018). [PDF]. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/toolkit/awareness-resources.html.

Wallet card (PDF)

Wallet Card. (2015). [PDF]. Waterloo Region Crime Prevention Council. https://preventingcrime.ca/our-work/overdose-prevention/.

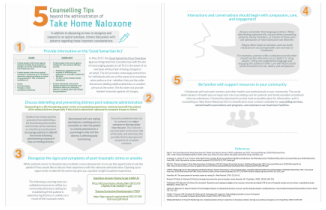

After the Overdose

- Participation in an opioid overdose, whether the victim, administering naloxone, calling 911, or being a bystander at the scene, can be very stressful

- In many cases, there is little to no follow-up or ability for individuals to discuss their feelings about being involved

- Anyone feeling anxious or worried after being involved in an overdose/administering naloxone should speak to a health and social service professional or community supports

- For people who have lost a loved one, health and social service professionals and community groups may be a source of information and support. Because of the opioid crisis, support groups specific to persons who have lost loved ones to overdose may be available

5 Counselling Tips Beyond the

Administration of Take Home Naloxone (PDF)

(Beazely, unpublished)

Stop and Think

Now that you have reviewed this content, consider the following scenarios:

A group of policy makers has proposed that “everyone” should have a naloxone kit on hand. Do you agree or disagree with this statement? Why?

Consider this question in light of what you have learned above.

Questions

References

BC Centre for Disease Control. (2017). BC overdose prevention services guide, 2017. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Guidelines%20and%20Manuals/Epid/Other/BC%20Overdose%20Prevention%20Services%20Guide_Jan2019.pdf

Boom, M., Niesters, M., Sarton, E., Aarts, L., Smith, T. W., & Dahan, A. (2012). Non-analgesic effects of opioids: Opioid-induced respiratory depression. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 18, 5994–6004.

Gupta, K., Nagappa, M., Prasad, A., Abrahamyan, L., Wong, J., Weingarten, T. N., & Chung, F. (2018). Risk factors for opioid-induced respiratory depression in surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 8, e024086.

Health Canada. (2019). About the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/about-good-samaritan-drug-overdose-act.html

McAuley, A., Munro, A., & Taylor, A. (2018). “Once I’d done it once it was like writing your name”: Lived experience of take-home naloxone administration by people who inject drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 58, 46–54.

Pattinson, K.T. (2008). Opioids and the control of respiration. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 100, 747–758.

Naloxone hydrochloride injection USP. (2011). Product monograph. Sandoz Canada. https://www.sandoz.ca/sites/www.sandoz.ca/files/Naloxone_HCl_PMe_20111104.pdf

Narcan nasal spray. (2017). Product monograph. Adapt Pharma Operations. https://www.narcannasalspray.ca/pdf/en/product_monograph.pdf

Wagner, K. D., Davidson, P. J., Iverson, E., Washburn, R., Burke, E., Kral, A. H., McNeeley, M., Jackson Bloom, J., & Lankenau, S. E. (2014). "I felt like a superhero": The experience of responding to drug overdose among individuals trained in overdose prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 157–165.