Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Discuss the impact of relaxation, distraction, and refocusing on the experience of pain.

- Describe non-pharmacological therapeutic options to manage pain including complementary alternative therapies (CATs).

- Discuss the efficacy of available non-pharmacological pain management modalities.

Key Concepts

- Non-pharmacological interventions and complementary alternative therapies (CATs) should be considered for all people experiencing acute or chronic pain.

- Perceptions of pain may intensify when a person is bored, isolated, or under stress.

- Emotional support may reduce the experience of pain whereas a lack of support may increase it.

- In hospice care, CATs are being used to increase comfort, decrease pain, promote relaxation, and increase quality of life.

- There are numerous studies of non-pharmacological interventions and CATs, but high-quality evidence on effectiveness is limited.

- Access barriers to a number of non-pharmacological interventions and complementary alternative therapies include limited availability and costs.

Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Pain

Persons experiencing chronic pain often seek out non-pharmacological interventions and complementary alternative treatments (CATs). There is evidence supporting the efficacy of non-pharmacological methods to reduce pain, however, more rigorous studies are needed and are underway (Bérengère et al, 2017).

NOTE: Health guidelines and pain management experts recommend the addition of these approaches for all persons experiencing pain or living with opioid use disorder.

Non-pharmacological interventions are generally introduced by a multidisciplinary team as part of an overall pain management approach. A wide variety of non-pharmacological modalities are available for use, although the cost of some approaches limits access. They include:

- behavioural interventions,

- physical activity,

- Indigenous healing practices,

- acupuncture, and

- massage therapy.

Behavioural Interventions in Pain Management

Behavioural interventions to manage pain are considered particularly helpful for persons experiencing stress, depression, and anxiety related to chronic pain. Examples of these interventions include the following:

KatarzynaBialasiewicz/iStock

- Cognitive behavioural therapy is a short-term, goal-oriented approach to psychotherapy that focuses on a person’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviours to increase quality of life and reduce disability.

- Regular mindfulness meditation is used to manage pain by reducing stress, depression, anxiety, and the experience of pain.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is an emerging behavioural intervention that employs mindfulness skills, acceptance, and cognitive strategies to address a person’s response to pain.

- Refocusing uses cognitive strategies to reduce pain; for example, refocusing on positive incremental changes in pain and function or directing attention to a non-painful part of the body and then imagining an altered sensation in that part of the body (e.g., a non-painful hand warming up).

- Stress reduction methods, which include progressive relaxation, guided imagery, and biofeedback.

Physical Activity to Reduce Pain

Physical activity may decrease inflammation, increase mobility, and stimulate the release of endogenous opioids. As a result, a variety of individual exercise initiatives and organized programs of physical activities are being used in pain management.

Examples include the following:

zoff-photo/iStock

- Walking is a frequently recommended method to increase global well-being and quality of life for persons with chronic pain.

- Tai chi is an accessible and low-cost Chinese mind-body exercise therapy that uses slow motion and weight shifting to reduce the pain from multiple conditions, including osteoarthritis, low back pain, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, herpes zoster, and rheumatoid arthritis (Kong et al., 2016).

- Yoga, which comprises physical poses, controlled breathing, and meditation to reduce pain by increasing flexibility, muscular strength, and mental and physical relaxation (Wieland et al., 2017).

- Aquatic exercise, a generally low-cost activity available in most communities, is supported by a considerable number of subjective reports.

Acupuncture for Pain

peakSTOCK/iStock

Acupuncture therapy is regulated in Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador, and the titles of “acupuncturist” and “traditional Chinese medicine practitioner” are protected in these provinces (Acupuncture Canada, n.d.). Eligible practitioners in these provinces are registered in their respective provincial acupuncture association. For example, Ontario practitioners must be registered with the College of Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners and Acupuncturists of Ontario. In British Columbia, they must be registered with the College of Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners and Acupuncturists of British Columbia.

NOTE: In Ontario, regulations allow registered acupuncture practitioners to do treatments on tissue below the dermis and mucous membrane.

Acupuncture has been found to improve conditions for people suffering from chronic neck, back, and pelvic pain, as well as chronic headaches (Küçük et al., 2015; Lam et al., 2013; van Tulder et al., 2013; Willich et al., 2006), although further studies are needed.

- It is suggested that if acupuncture treatment is used, it should be a supplement to, and not a replacement for, other types of treatment (Willich et al., 2006).

Indigenous Healing Practices

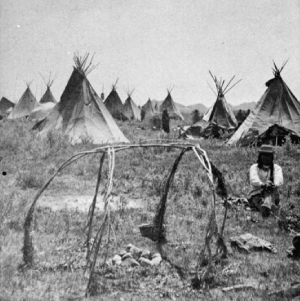

Indigenous people with chronic pain use a wide range of traditional healing practices including the sweat lodge (Greensky et al., 2014).

The sweat lodge is a dome in which heat is generated by pouring water onto hot rocks. The steam then increases the temperature inside the dome, which encourages sweating. It has been described as a powerful form of healing, with reported physical, psychological, and spiritual benefits for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons.

Huffman, L. Sweat lodge, Sioux Village / L. A. Huffman, Miles City, Montana [Online Image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SweatLodge.jpg.

James Mahan/iStock

There is a small amount of data regarding sweat lodges in the treatment of chronic pain.

- Benefits of sauna bathing, which have been reported to alleviate some types of pain such as rheumatic arthritis (Isomäki, 1988), have been extrapolated to Indigenous sweat lodges because of the similarity in inducing acute heat stress (Heinonen & Laukkanen, 2017).

Sweat lodges may be included as an adjunctive therapy in chronic pain in clients who are interested and have access to such a facility. They may be especially helpful for Indigenous people experiencing chronic pain because of the spiritual and traditional cultural meanings associated with the sweat lodge.

Yoga

fizkes/iStock

Yoga can be used for people with mild to moderate back pain and fibromyalgia. Additionally, it can help with psychological factors; however, more evidence is needed to determine the efficacy of yoga as a means of pain reduction.

Studies have been limited but continue to expand. Back pain is the most commonly studied condition. There is anecdotal evidence that yoga practice can be modified for specific clients and conditions.

It is recommended that people with chronic pain seek out certified practitioners with experience in providing practices specifically for pain.

Some insurance plans may cover the cost of yoga as a treatment. Less expensive community programs are available in some areas.

The research suggests improvements in three specific areas:

Physiological

- improved flexibility and strength

Behavioural

- decreased isolation

- decreased fatigue and other constitutional symptoms

- decreased experience of pain

Psychological

- increased self-awareness

- increased understanding of pai

- increased sense of health

- optimism

- increased acceptance of pain

- improved self-efficacy

Therapeutic Massage for Pain Relief

julief514/iStock

Massage is a popular treatment for people with low back pain, neck pain, and headaches. Therapeutic massage may relieve pain by relaxing muscles, tendons, and joints, as well as by relieving tension and stress.

Many variables can affect the quality of massage, including technique, number of sessions, intensity, location of the pain in the body, and so on (Furlan et al., 2015). Training of massage therapists also varies widely.

Overall, there is not enough evidence to recommend massage therapy for pain.

Efficacy of Non-Pharmacological Pain Interventions

Although studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of non-pharmacological pain interventions, in general they have not been of high quality, and stronger evidence is needed to support these methods.

Aquatic exercise

- A 2008 meta-analysis of aquatic exercise compared with land-based exercise failed to show any significant difference between the two interventions in terms of analgesia or improved gait (Hall et al. 2008).

- More recent studies, however, of aquatic exercise that focused on low back pain and pain related to osteoarthritis of the knee demonstrated a low-impact benefit in pain relief and improved function (Sirous et. al., 2019).

Yoga

- While some studies found no change in pain using yoga (Ward et al., 2013), a systematic review of 12 trials found that yoga was better than no exercise and resulted in a small to moderate improvement in back pain. These differences, however, were not considered to be clinically significant (Wieland et al., 2017).

Acupuncture

- Although studies have reported that acupuncture treatment has notable benefits when compared with placebo acupuncture treatments, both postintervention and three months after intervention, other meta-analyses found that the benefits of acupuncture are not significant.

- More high-quality studies with similar methodologies are needed to assess the impact of acupuncture on pain management (van Tulder et al., 2013).

Sweat lodges

- Although no research has been conducted evaluating the efficacy of sweat lodges in reducing pain, a small, randomized, controlled trial found that regular sauna bathing reduced the intensity but not the duration of headaches in clients with chronic tension-type headache (Kanji et al., 2015)

Massage therapy

- Evidence supporting the benefits of massage therapy on pain management is lacking. For example, a Cochrane review of 12 randomized, controlled trials concluded that there is no evidence that massage is an effective treatment for lower back pain other than on a short-term basis (Furlan et al., 2015).

- Another review found that massage can be safely administered to young and middle-age adults with chronic pain and can have short term benefits, but no study had examined long term benefits at the time this review was conducted (Reid et al., 2008).

Yuttapong/iStock (aquatic exercise, yoga); Mari_C/iStock (acupuncture, massage therapy); Fidan Babayeva/iStock (sweat lodge)

In summary, although the use of non-pharmacological options to manage pain is increasing, further research is needed on their impact.

Questions

References

Ackerman, C. E. (2020). How does acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) work? PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/act-acceptance-and-commitment-therapy/

Acupuncture Canada. (n.d.). Regulation and education. https://www.acupuncturecanada.org/acupuncture-101/regulation-and-education/

Bérengère, H., El-Khatib, H., & Arbour, C. (2017). Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for chronic pain: An umbrella review on various CAM approaches. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 79(B), 192–205.

Centre for Effective Practice. (2018). Chronic non-cancer pain. https://cep.health/clinical-products/chronic-non-cancer-pain/

Furlan, A. D., Giraldo, M., Baskwill, A., Irvin, E., & Imamura, M. (2015). Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, Article CD001929. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub3

Garrett, M. T., Torres-Rivera, E., Brubaker, M., Portman, T. A. A., Conwill, W., & Grayshield, L. (2011). Crying for a vision: The Native American sweat lodge ceremony as therapeutic intervention. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 318–325.

Greensky, C., Stapleton, M. A., Walsh, K., Gibbs, L., Abrahamson, J., Finnie, D. M., Hathaway, J. C., Vickers-Douglas, K. S., Cronin, J. B., Townsend, C. O., & Hooten, W. M. (2014). A qualitative study of traditional healing practices among American Indians with chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 15(10), 1795–1802. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12488

Hall, J., Swinkels, A., Briddon, J., & McCabe, C. S. (2008). Does aquatic exercise relieve pain in adults with neurologic or musculoskeletal disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89(5), 873–883.

Heinonen, I., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2017). Effects of heat and cold on health, with special reference to Finnish sauna bathing. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 314(5), R629–R638. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00115.2017

Isomäki, H. (1988). The sauna and rheumatic diseases. Annals of Clinical Research, 20(4), 271–275.

Kanji, G., Weatherall, M., Peter, R., Purdie, G., & Page, R. (2015). Efficacy of regular sauna bathing for chronic tension-type headache: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2013.0466

Kline, G. A. (2009). Does a view of nature promote relief from acute pain? Journal of Holistic Nursing, 27(3), 159–166.

Kong, L. J., Lauche, R., Klose, P., Bu, J. H., Yan, S. C., Guo, C. Q., Dobos, G., & Cheng, Y. W. (2016). Tai chi for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scientific Reports, 6, 25325. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25325

Küçük, E. V., Suçeken, F. Y., Bindayı, A., Boylu, U., Onol, F. F., &Gümüş, E. (2015). Effectiveness of acupuncture on chronic prostatitis–chronic pelvic pain syndrome category IIIB patients: A prospective, randomized, nonblinded, clinical trial. Urology, 85(3), 636–640.

Lam, M., Galvin, R., & Curry, P. (2013). Effectiveness of acupuncture for nonspecific chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine, 38(24), 2124–2138

Lilley, L. L., Rainforth Collins, S., Snyder, J., & Stewart, B. (2017). Pharmacology for Canadian health care practice (3rd ed.). Elsevier Canada.

Potter, P. A., Perry, A. G., Ross-Kerr, J. C., Wood, M. J., Astle, B. J., & Duggleby, W. (2017). Canadian fundamentals of nursing (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2013). Assessment and management of pain (3rd ed.).

Reid, M. C., Papaleontiou, M., Ong, A., Breckman, R., Wethington, E., & Pillemer, K. (2008). Self-management strategies to reduce pain and improve function among older adults in community settings: A review of the evidence. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.), 9(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00428.x

Sirous, A., Dadarkhah, A., Rezasoltani, Z., Raeissadat, S. A., Mofrad, R. K., & Najafi, S. (2019). Randomized controlled trial of aquatic exercise for treatment of knee osteoarthritis in elderly people. International Medicine and Applied Science, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1556/1646.11.2019.19

van Tulder, M. W., Cherkin, D. C., Berman, B., Lao, L., & Koes, B. W. (2013). The effectiveness of acupuncture in the management of acute and chronic low back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine, 24(11), 1113–1123.

Vickers, A. J., Vertosick, E. A., Lewith, G., MacPherson, H., Foster, N. E., Irnich, D., & Witt, C. M. (2018). Acupuncture for chronic pain: Update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. Journal of Pain, 19(5), 455–474.

Vowles, K. E., Fink, B. C., & Cohen, L. L. (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: A diary study of treatment process in relation to reliable change in disability. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(2), 74–80.

Ward, L., Stebbings, S., Cherkin, D., & Baxter, G. D. (2013). Yoga for functional ability, pain and psychosocial outcomes in musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Review of yoga for musculoskeletal conditions. Musculoskeletal Care, 11(4), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1042

Wieland, L. S., Skoetz, N., Pilkington, K., Vempati, R., D’Adamo, C. R., & Berman, B. M. (2017). Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, Article CD010671. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010671.pub2

Willich, S. N., Reinhold, T., Selim, D., Jena, S., Brinkhaus, B., & Witt, C. M. (2006). Cost-effectiveness of acupuncture treatment in patients with chronic neck pain. Pain, 125(2), 107–113.

Wren, A. A., Wright, M. A., Carson, J. W., & Keefe, F. J. ((2011). Yoga for persistent pain: New findings and directions for an ancient practice. Pain, 122(3), 477–480.

Yalfani, A., Maleki, B., & Raeisi, Z. (2019). The effect of aquatic exercise therapy on the pain, disability and gait parameters of women with chronic low back pain. Scientific Journal of Management Systems, 17(18), 57–67.