Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe the factors that influence an individual’s experience of pain.

- Identify risk factors associated with the development of chronic pain.

- Discuss the biopsychosocial model of pain and its influence on how pain is understood.

- List the social, psychological, spiritual, and physical aspects of pain.

- Discuss how treatment options can affect a person’s experience of pain.

Key Concepts

- Pain, and particularly chronic pain, impacts not only the individual experiencing pain but also their family and friends, the workplace, the community, and society at large. All aspects of life can be affected.

- The way pain is treated and understood also has an impact on the individual and others.

- Chronic pain is now understood and categorized as a unique health issue or illness.

- One in five Canadians experiences chronic pain.

- Chronic pain is more prevalent among older adults, females, Indigenous Peoples, veterans, and groups of people who experience social inequities and discrimination.

- Many of the populations described above, and those experiencing substance use disorders or mental health issues, are at risk for unmanaged or undertreated pain because of stigma, fear, and anxiety related to the use of opioids in the management of chronic pain.

Prevalence and Impact of Pain

One in five Canadians experiences chronic pain (Canadian Pain Task Force, 2019). Chronic pain is an individual experience that is affected by and affects all aspects of a person’s life and the lives of those who care for them.

NOTE: Pain is an individual, subjective experience and therefore pain management needs to take into account an individual’s experience of pain beyond the physical symptoms.

Health and social service providers need to address the social determinants of health that not only are related to the experience of pain but can also be barriers or facilitators in the successful management of pain.

Biopsychosocial Model of Pain

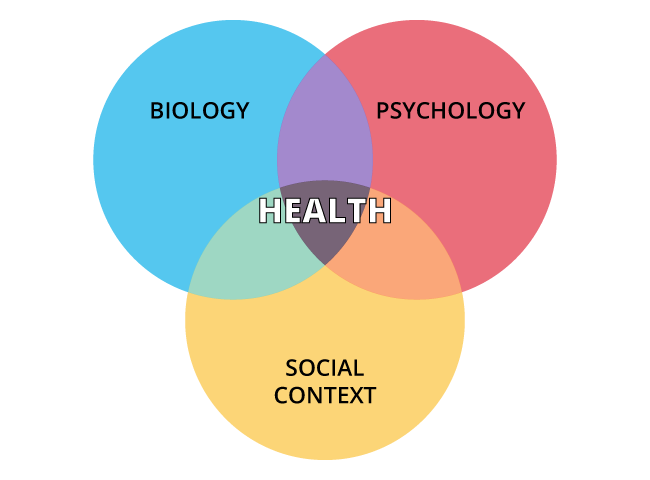

An accepted model for understanding the assessment, prevention, and treatment of chronic pain is the biopsychosocial model. Health is understood to incorporate biological, psychological, and social factors, as shown below.

Biopsychological approach to understanding health

Biology

- Gender

- Physical illness

- Disability

- Genetic vulnerability

- Immune function

- Neurochemistry

- Stress reactivity

- Medication effects

Psychology

- Learning/memory

- Attitudes/beliefs

- Personality

- Behaviours

- Emotions

- Coping skills

- Past trauma

Social Context

- Social supports

- Family background

- Cultural traditions

- Social/economic status

- Education

Ong, L. (n.d.). Health psychology. Perspectives Clinics. http://perspectivesclinic.com/health-psychology/

This model recognizes that multiple biological, psychological and social factors can be challenging or strengthening to a person’s health.

Pain is considered to be more than a biomedical phenomenon of the neurological expression of painful stimuli. Pain is a complex interaction of physiological, psychological, and social factors that influence the experience of pain. As such, pain is experienced differently by each individual because of the unique and dynamic interactions among those factors.

- Identifying the interactions of multiple factors is required in the assessment of the individual’s experience of pain. This provides the basis for interventions designed to reduce the risk of chronic pain and for treating chronic pain and its consequences.

Physical Impact of Pain

The biopsychosocial model of pain postulates that all aspects of a person’s life can affect and be affected by their experience of pain. Thus, a person’s experience of physical pain will be affected by their psychological status and their social experiences.

The impact of physical pain on psychosocial factors is illustrated by the following examples.

Pain that decreases a person’s ability to carry out activities of daily living such as dressing, feeding, hygiene, cooking, shopping, and so on, will Increase dependence on others.

Halfpoint/iStock

Disability because of pain creates a need for assistance from others and mobility aids.

yacobchuk/iStock

Fatigue or exhaustion resulting from pain impacts social participation.

fizkes/iStock

Pain may impact sexual arousal, which may alter intimate relationships.

AntonioGuillem/iStock

Social Impact of Pain

A person living with chronic pain may also be impacted on a social level. Examples include the following:

- isolation from family and friends

- loss of social connections

- loss of social support

- decreased recreation or leisure activities and community activities

- school or work absences

- loss of productivity or diminished efficiency at work

- lost wages/income

- changes in important social roles such as caregiver or wage earner, with corresponding perceived decrease in social contacts or feelings of self-worth

- altered relationships with friends and family or loss of social contacts; less participation in social or family activities or events

- grief over loss of social connections, activities, and relationships

Psychological Impact of Pain

The impact of psychological pain may be evidenced in the following ways:

Anger and Irritability

Fear

Caused by:

- catastrophizing pain (i.e., a negative appraisal of pain that assumes the worst outcomes, constructs minor problems and major dilemmas)

- lack of predictable pattern of episodes of pain

- lack of predictable improvement in pain intensity or frequency

- unknown etiology/cause of the pain

Depression

- The prevalence of depression is estimated to be very high among persons experiencing chronic pain.

- Recent studies have suggested rates as high as 72 to 86 percent (Sheng et al, 2017).

- The diagnosis of depression in persons experiencing chronic pain, however, is challenging as several of the somatic symptoms (insomnia, preoccupation with physical symptoms, weight loss) overlap with depression.

Increased risk of self-harm or suicide

- The risk of suicide among persons experiencing chronic pain has been estimated to be two to three times the rate among the general adult population.

- Risk factors for suicidal ideation, behaviour, or completion include the following (Culpepper & Shhreiber, 2013):

- any type of chronic pain

- multiple pain conditions

- poor perceived mental health

- pain catastrophizing (magnification, helplessness, hopelessness)

- perceived burdensomeness

- thwarted belongingness

- depression

- alcohol misuse

- anger issues

- unemployment or financial concerns

- strong family history of suicide

- sleep problems

Sleep Disturbance

Cognitive changes

- slower processing

- selective attention

- changes in memory

- changes in executive function

- lowered ability to pay attention and focus on tasks

- problems in planning, organizing, prioritizing

- difficulty regulating emotions

Other Factors

Spiritual and Emotional Impact

Spiritual well-being can be negatively affected by chronic pain. Spiritual suffering is commonly experienced by persons with significant or life-threatening illness and their families. The inability to clinically manage physical pain can be due, in part, to unmet emotional and spiritual needs.

NOTE: Spiritual distress is experienced in 25 percent of people receiving cancer treatment (Schultz et al., 2017).

Definition

- Spiritual Distress

- A disruption in the life principle that pervades the whole being of a person and that integrates and transcends biological and psychosocial nature. (NANDA International, n.d.)

A person experiencing spiritual distress may express concern with the meaning of life and death, question the meaning of suffering or of their own existence, verbalize inner conflict about beliefs, express anger towards God or other supreme being (however defined), or actively seek spiritual assistance (O’Toole, 2003).

- In a study on persons with substance use disorder, individuals reported that feeling drowsy on opioids resulted in a withdrawal from spiritual obligations. This can create a negative, downward cycle in which diminished spiritual well-being increases feelings of chronic pain and dependence on opioids. On the other hand, those who were able to manage their chronic pain with opioids reported a fulfilment of spiritual obligations (O’Toole, 2003).

- Spiritual well-being may also be beneficial for treatment success. Among a sample of 312 individuals recovering from opioid use disorder, those with significantly lower scores on a spiritual well-being scale were more likely to relapse than those who with higher scores (O’Toole, 2003).

As part of the assessment and intervention planning process, health and social service professionals must be aware that those who experience chronic pain might have feel diminished spiritual well-being, which can lead to increased substance use and form a repetitive downward cycle.

Impact on Families and Supports

Pain can also negatively impact families and support people. For example, families of persons experiencing chronic pain and varying degrees of related disability may be required to take on new roles, responsibilities, and experiences such as:

- caregiving roles that they may not be prepared for

- roles that require them to be active in the supervision or evaluation of treatment or that require them to participate in treatment

- experiences of physical deterioration, sadness, frustration, and impotence, and feelings of being overwhelmed

Family members’ lives may be affected in many of the same ways as the person experiencing chronic pain:

- They can experience depression and anxiety and have poor coping mechanisms.

- Children of person’s living with chronic pain tend to have poorer outcomes related to their own experience of pain, health, emotional or psychological health, and family functioning.

Assessment and treatment for chronic pain, whether related to cancer or other causes, requires a comprehensive assessment of the family, friends, and support systems involved in the client’s life. Treatment and management plans should include interventions to reduce risk of poor outcomes such as:

- family counselling,

- therapeutic interventions and

- access to community support services.

Strengths should be identified and built upon in all intervention plans.

Questions

References

Canadian Pain Task Force. (2019). Chronic pain in Canada: Laying a foundation for action. Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2019/canadian-pain-task-force-June-2019-report-en.pdf

Culpepper, L. & Shhreiber, J. (2013). Suicidal ideation and behavior in adults. UpToDate. 2006 with annual revision through May 2013.

Dueñas, M., Begoña, O., Salazar, A., Mico, J. A., & Failde, I. (2016). A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. Journal of Pain Research, 9, 457–467.

Higgins, K. S., Birnie, K. A., Chambers, C. T., Wilson, A. C., Caes, L., Clark, A. J., Lynch, M., Stinson, J., & Campbell-Yeo, M. (2015). Offspring of parents with chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of pain, health, psychological, and family outcomes. Pain, 156(11), 2256–2266.

Knaster, P., Estlander, A.-M., Karlsson, H., Kaprio, J., & Kalso, E. (2016). Diagnosing depression in chronic pain patients: DSM-IV major depressive disorder vs. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). PLoS One, 11(3), Article e0151982. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151982

NANDA International. (n.d.). Nursing diagnoses list. http://www.nandanursingdiagnosislist.org/functional-health-patterns/spiritual-suffering/

O’Toole, M. (2003). Miller-Keane encyclopedia and dictionary of medicine, nursing, and allied health (7th ed.). Saunders.

Potter, P. A., Perry, A. G., Ross-Kerr, J. C., Wood, M. J., Astle, B. J., & Duggleby, W. (2017). Canadian fundamentals of nursing (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Racine, M. (2018). Chronic pain and suicide risk: A comprehensive review. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 87(Part B), 269–280.

Riva, P., Wesselmann, E. D., Wirth, J. H., Carter-Sowell, A. R., & Williams, K. D. (2014). When pain does not heal: The common antecedents and consequences of chronic social and physical pain. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 36, 329–346.

Sheng, J., Liu, S., Wang, Y., Cui, R., & Zhang, X. (2017). The Link between Depression and Chronic Pain: Neural Mechanisms in the Brain. Neural plasticity, 2017, 9724371. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9724371

Turk, D. C., Fillingim, R. B., Ohrbach, R., & Patel, K. V. (2016). Assessment of psychosocial and functional impact of chronic pain. American Pain Society, 17(9), T21–T49.

Schultz, M., Meged-Book, T., Mashiach, T., & Bar-Sela, G. (2017). Distinguishing between spiritual distress, general distress, spiritual well-being, and spiritual pain among cancer patients during oncology treatment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(1), 66–73.