Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Summarize trends related to the number of deaths and hospitalizations resulting from opioid use across Canada.

- Describe geographic differences in opioid use, hospitalization, and fatality rates.

- Explain the effects of opioid use among different sub-populations, including adolescents and young adults, older adults, and Indigenous populations.

Key Concepts

- Western Canada is the region of the country with the highest rates of opioid-related overdose, but rates have increased in other regions such as Ontario and Yukon.

- The majority of opioid-related deaths occurred among males (73 percent), and the highest percentage of opioid-related deaths was among those aged 30–39 (28 percent).

- In Ontario, fentanyl (pharmaceutical or non-pharmaceutical) and fentanyl analogues directly contributed to almost three-quarters (71.2 percent) of accidental opioid-related deaths in 2017.

- From 2013 to 2015, rates of opioid use among youth and young adults decreased.

- In recent years, adults 65 and older have consistently had the highest rates of hospitalization in Canada for opioid poisoning, reaching 20.1 hospitalizations per 100,000 population in 2014–2015.

Opioid Use and Mortality in Canada

13,900 deaths

Canadians who died from apparent opioid-related overdose (Jan 2016-June 2019)

94% accidental

Opioid-related deaths that were accidental (Jan – June 2019)

73% male

Opioid-related deaths were male (Jan – June 2019)

28% aged 30-39

The highest percentage of opioid-related deaths were in this age group.

Public Health Agency of Canada (2019);

Amanda Goehlert/iStock (death); LysenkoAlexander/iStock (accident); Fourleaflover/iStock (male); mayrum/iStock (age)

Western Canada is the most impacted region of the country, but rates have increased dramatically in Ontario and Yukon as well. In fact, between 2010 and 2016, fentanyl-related deaths examined in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia showed an increase in all provinces (Fischer et al., 2018).

In Ontario, the overall rate of opioid-related mortality increased by 285 percent between 1991 and 2015. By 2015, on average nearly two people died of an opioid-related cause every day (Gomes et al., 2018).

Fentanyl (pharmaceutical or non-pharmaceutical) and fentanyl analogues directly contributed to approximately three-quarters (71.2 percent) of accidental opioid-related deaths in 2017 (Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario), Office of the Chief Coroner, Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, & Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, 2019).

For an up-to-date picture of the status of opioid-related harms in Canada, please take a moment to visit the Government of Canada Public Health Infobase describing Opioid-related harms in Canada.Pay special attention to the statistics under “Deaths”.

Watch this short video from the Government of Canada, which introduces Canada’s opioid awareness campaign.

Hospitalizations for Opioid Use in Canada

Between 2007 and 2017, the rate of hospitalizations in Canada for opioid poisonings increased by over 50 percent, with the largest increases occurring in the last three of those years (Canadian Institute for Health Information & Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addition, 2016).

- There was an average of more than 17 hospitalizations per day in 2017, compared to an average of 9 hospitalizations per day in 2008 in Canada (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019).

- In 2020, 64 percent of the 1,067 hospitalizations for opioid-related poisoning were unintentional (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2020).

- Northern and Western regions of Canada have the highest rates of hospitalizations related to opioid toxicity.

- Older adults (60+ years) have consistently had the highest rates of hospitalization for opioid poisoning (29 percent), although the fastest growing rates of hospitalizations were seen in younger age groups (15- to 24-year-olds and 24- to 44-year-olds).

- From 2013 to 2017, the rate of opioid poisoning hospitalizations increased by 48 percent among males and 10 percent among females.

Between 2016 and 2017, rates of emergency department (ED) visits for opioid poisonings rose by 73 percent in Ontario and 23 percent in Alberta (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018).

- “Rates of hospitalizations due to opioid poisoning are highest for patients who live in communities with a population between 50,000 and 99,999. Communities with a population greater than 500,000 have the lowest rates of hospitalizations” (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018).

- In Yukon, “rates of ED visits due to opioid poisoning increased more than four-fold and rates due to opioid use disorders increased more than three-fold between 2013 and 2017” (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018).

- In 2019, a majority of emergency medical services used for suspected opioid-related overdoses were by males (72 percent), mostly between the ages of 20 and 39 (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2019).

Illicit Drug Usage and Deaths Related to Opioid Use

Opioids can be used for self-medication of physical pain, emotional pain, and trauma, or to avoid symptoms of opioid withdrawal.

- Although these are medical reasons, when used outside the medical system they are sometimes called non-medical use.

- This type of use is also sometimes referred to as misuse or abuse in the literature.

Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, are extremely potent and have become more common on the illegal drug market.

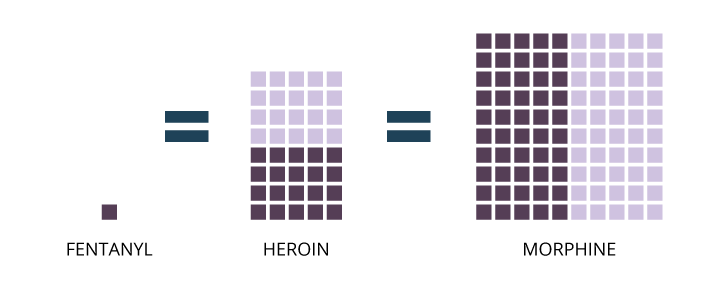

Fentanyl is 20 to 40 times as potent as heroin and 50 to 100 times as potent as morphine, meaning a dose of the drug the size of a few grains of salt can be lethal.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

In recent years, the high rates of opioid-related deaths are mostly due to an increase in illicitly-manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl-like drugs (e.g., carfentanil).

- Between 2011 and 2015 in Ontario, oxycodone-related deaths fell by approximately 25 percent, but fentanyl-related deaths increased by more than 50 percent (Belzak & Halverson, 2018).

- In British Columbia, fentanyl and fentanyl analogues were involved in 67 percent of the fatal overdose cases in 2016, and it became a public health emergency in the province. By 2018, this number had increased to over 85 percent (Karamouzian et al., 2020).

- In Quebec there were seven times as many fentanyl-related deaths in 2015 as there were in 2005 (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction, 2017).

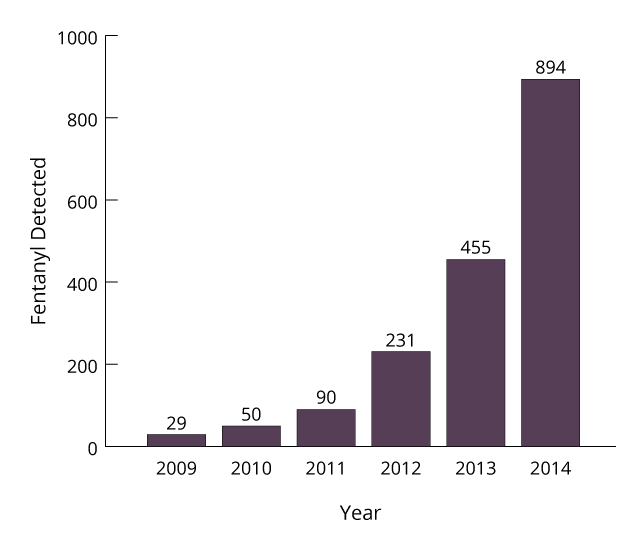

Data provided by Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Services show fentanyl has been detected in growing seizures of both diverted prescription and illicitly produced substances.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Aside from overdose mortality, fentanyl can also produce other significant harms to an individual, such as non-fatal overdoses and substance use disorder.

For more information on illegal/unregulated opioids, see Module 1, Topic G.

Opioid Use in Adolescents and Young Adults

Opioid use in adolescents is correlated with substance use, being at risk for substance use disorders, and behavioral issues.

- The onset of mental health and substance use problems often occurs during adolescence and young adulthood.

- Because a higher proportion of adolescents are using opioids for non-medical purposes, opioid prescriptions in adolescents require special consideration.

- Canadian epidemiological data on the use of non-prescription opioids among youth have been scarce, with more data available in recent years.

- Between 2010 and 2015 in Ontario, the most substantial increase in opioid-related deaths occurred among those aged 15 to 24 years (Gomes, 2018).

- In the past five years, opioid-related deaths nearly doubled among young adults between 15 and 24 years old in Ontario.

- In Canada, this age group had the fastest-growing rates of hospitalizations related to opioid overdoses between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (Shannon et al., 2018).

- The rate of ED visits increased by 53 percent in Alberta and 22 percent in Ontario between 2010–2011 and 2014–2015 (Canadian Institute for Health Information & Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2016).

- The majority of opioid-related poisonings that resulted in a visit to the ED were intentional (52 percent) in this age group (Canadian Institute for Health Information & Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2016).

- In 2015, the rate of past-year use of opioid pain relievers among youth ages 15–19 was 7.4 percent and was 12.8 percent for 20- to 24-year-olds. This is lower than numbers reported in 2013, where 13.6 percent of youth ages 15 to 19 reported past-year use of opioid pain relievers compared to 15.9 percent of those between 20 and 24 year of age (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction, 2017).

- The Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey conducted in 2017 by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health reported that 10.6 percent of Ontario students in Grades 7 to 12 used opioids for non-medical purposes in the last year, which was down from 12.4 percent in 2013.

- In New Brunswick during 2012, 11.1 percent of students in Grades 7, 9, 10, and 12 reported past-year nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers (Gupta et al., 2013).

Please take the time to observe the following adolescent case study from the Opioid Partnership

Jennifer is a 15-year-old female who has come to the family doctor’s office today with her mother Laura. Laura is worried that her daughter may be misusing her pain medication.

Older Adults and Opioid Use

Many people develop chronic pain as they age and are more likely to be prescribed opioids for longer periods. Older adults are more likely than any other age group to experience harm related to opioid use.

- Older adults are being prescribed opioids for a longer period of time, an average of 18.6 days in 2017 compared with only 6.6 days for people ages 15 to 24 (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019).

- The rate of opioid use among older Canadian adults was 13.2 percent in 2015, down from 16.2 percent in 2013 (Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse and Addiction, 2017).

- “In recent years, adults 65 and older have consistently had the highest rates of hospitalization for opioid poisoning, reaching 20.1 hospitalizations per 100,000 population in 2014–2015. While older adults represented 16 percent of the population in 2014–2015, they accounted for about a quarter of all hospitalizations for opioid poisonings in that year” (Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse and Addiction, 2017).

High rates of opioid poisonings causing hospitalization among seniors may be due to increased rates of taking multiple medications, biological changes to the body that occur with older age, and comorbid conditions (Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse and Addiction, 2019).

Impact of Opioid Use on Indigenous Populations

Indigenous populations (including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) have been heavily impacted by opioid-related harm and disproportionately affected by substance use.

“First Nations people were five times more likely than their non–First Nations counterparts to experience an opioid-related overdose event and three times more likely to die from an opioid-related overdose”

In British Columbia, compared to non-Indigenous women, Indigenous women experience eight times as many opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) events and five times as many deaths from overdose as non‐ Indigenous women, and Indigenous men experienced three times as many OIRD events and deaths as non‐Indigenous men (First Nations Health Authority, 2017).

First Nations people were twice as likely to be prescribed an opioid as non–First Nations individuals and tended to be at least five years younger than their non–First Nations counterparts when prescribed opioids (Belzak & Halverson, 2018).

The disparity of opioid use problems seen in these communities is understood to be rooted in a history of colonization causing:

- trauma,

- loss,

- poverty, and

- family separation, which had seismic and multi‐generational impacts on the mental well-being of Indigenous Peoples.

The cultural history and socioeconomic context of Indigenous communities must be considered when understanding the impact of opioid use disorder in this population.

Regional comparisons between First Nations and other ethnic communities across the nation are not feasible because of the poor availability of this type of information.

The Government of Canada is making efforts to support Indigenous communities in addressing the opioid crisis in the following ways (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019):

- distributing public awareness wallet cards about signs of an overdose through more than 55 Indigenous and First Nations groups

- enhancing delivery of culturally appropriate substance use treatment and prevention services in First Nations and Inuit communities

- supporting comprehensive, childcare at community-based opioid agonist treatment sites in First Nations and Inuit communities

- facilitating access to naloxone, including in remote and isolated First Nations and Inuit communities

The Government of Canada has produced wallet cards for quick reference in the event of a suspected opioid overdose. Please review the information on the Opioid overdose: wallet card.

You can order print copies of this resource from the Government of Canada site.

Questions

References

Belzak, L., & Halverson, J. (2018). Evidence-synthesis—The opioid crisis in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 38(6), 224.

Boak, A., Hamilton, H. A., Adlaf, E. M., & Mann, R. E. (2017). Drug use among Ontario students, 1977–2017: Detailed findings from the Ontario student drug use and health survey (CAMH Research Document Series No. 46). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Brands, B., Paglia-Boak, A., Sproule, B. A., Leslie, K., & Adlaf, E. M. (2010). Nonmedical use of opioid analgesics among Ontario students. Canadian Family Physician, 56(3), 256–262.

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse & Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use. (2015). CCENDU Bulletin: Deaths involving fentanyl in Canada, 2009–2014. http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-CCENDU-Fentanyl-Deaths-Canada-Bulletin-2015-en.pdf

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction. (2017). Canadian drug summary: Prescription opioids. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Canadian-Drug-Summary-Prescription-Opioids-2017-en.pdf

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2015). Opioids, driving and implications for youth. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Opioids-Driving-Implications-for-Youth-Summary-2015-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information & Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2016). Hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to opioid poisoning in Canada.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2014). Drug use among seniors on public drug programs in Canada, 2012.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). Opioid-related harms in Canada (Chartbook). https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/opioid-harmschart-book-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2019). Opioid prescribing in Canada: How are practices changing?

Canadian Psychological Association. (2019). Recommendations for addressing the opioid crisis in Canada. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Task_Forces/OpioidTaskforceReport_June2019.pdf

Chief Public Health Officer. (2018). Report on the state of public health in Canada, 2018: Problematic substance use in youth. (2018). Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/2018-preventing-problematic-substance-use-youth/2018-preventing-problematic-substance-use-youth.pdf

Emerson, B., Haden, M., Kendall, P., Mathias, R., & Parker, R. (2005). A public health approach to drug control in Canada. Health Officers Council of British Columbia.

First Nations Health Authority. (2017). Overdose data and First Nations in BC: Preliminary findings. https://www.fnha.ca/newsContent/Documents /FNHA_OverdoseDataAndFirstNations InBC_PreliminaryFindings_FinalWeb.pdf

Fischer, B., Vojtila, L., & Rehm, J. (2018). The “fentanyl epidemic” in Canada—Some cautionary observations focusing on opioid-related mortality. Preventive Medicine, 107, 109–113.

Gomes, T. (2018). Latest trends in opioid-related deaths in Ontario: 1991 to 2015. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. https://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ODPRN-Report_Latest-trends-in-opioid-related-deaths.pdf

Gomes, T., Greaves, S., Tadrous, M., Mamdani, M. M., Paterson, J. M., &Juurlink, D. N. (2018). Measuring the burden of opioid-related mortality in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 12(5), 418–419. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000412

Government of Canada. (2017). National report: Apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada.

Government of Canada. (2019). National report: Fentanyl. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/controlled-illegal-drugs/fentanyl.html

Gupta, N., Wang, H., Collette, M., & Pilgrim, W. (2013). New Brunswick student drug use survey report 2012. Province of New Brunswick Department of Health.

International Narcotics Board. (2012). Estimated world requirements for 2013. United Nations. https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2012/Narcotic_Drugs_Report_2012.pdf

Kahina, A., James, D. M., Ramona, A., Julie, L., & Samuel, I. P. (2018). At-a-glance opioid surveillance: monitoring and responding to the evolving crisis. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 38(9), 312.

Karamouzian, M., Papamihali, K., Graham, B., Crabtree, A., Mill, C., Kuo, M., Young, S., & Buxton, J. A. (2020). Known fentanyl use among clients of harm reduction sites in British Columbia, Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy, 77, 102665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102665

Lisa, B., & Jessica, H. (2018). Evidence synthesis—The opioid crisis in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 38(6), 224.

McCabe, S. E., Veliz, P., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2016). Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder symptoms at age 35: A national longitudinal study. Pain, 157(10), 2173.

McLean, A. J., & Le Couteur, D. G. (2004). Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacological Reviews, 56(2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.56.2.4. PMID: 15169926

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario), Office of the Chief Coroner, Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, & Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. (2019). Opioid mortality surveillance report: Analysis of opioid-related deaths in Ontario July 2017–June 2018. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Government of Canada supports efforts to better understand how substance use affects Indigenous communities. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2019/07/government-of-canada-supports-efforts-to-better-understand-how-substance-use-affects-indigenous-communities.html

Shannon, O., Vera, G., & Krista, L. (2018). At-a-glance-hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to opioid poisoning in Canada. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy, and Practice, 38(6), 244.

Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. (2019). National report: Opioid-related harms in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids

Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. (2020). Opioid-related harms in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids

Statistics Canada. (2015). Canadian tobacco, alcohol and drugs survey: Summary of results for 2013.