Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Define the term opioid.

- Recall the regulatory status of prescription and unregulated opioids.

- Review the list of regulated (legal) opioids available in Canada.

- Review the list of unregulated (illegal) opioids that have been identified in North America.

- Review the dosage forms and routes of administration of opioids.

- Discuss the impact of unregulated fentanyl and its analogues on opioid-related mortality.

Key Concepts

- Opioids are drugs that have morphine-like effects in the body and activate opioid receptors.

- Opioids are regulated drugs in Canada, they require a prescription (with the exception of some products containing codeine), and there are additional restrictions and regulations for opioid prescriptions.

- Several regulated opioids are available in Canada, including codeine, morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, and others.

- Unregulated opioids are also present in the illegal market in Canada, these include primarily fentanyl and its analogues, including methylfentanyl and carfentanil.

- There are several ways to administer opioids for medical or non-medical purposes, including oral administration and injection.

- Opioids differ in potency: how much is needed for a particular effect.

- The increase in opioid overdose and mortality that started in the mid-2010s is due primarily to the increase in the prevalence of unregulated fentanyl and its analogues in North America.

Opioids

Opioids are a class of compounds defined by their pharmacological activity, not their source or chemical structure.

The original, natural opioid is morphine. It is derived from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) seed pod resin, and it is an opioid receptor agonist (meaning it activates opioid receptors in the body).

Opioids vs Opiates

Technically, opioids are drugs that have morphine-like effects, i.e., they activate opioid receptors, whereas opiates are compounds derived from the opium poppy.

So, morphine is an opioid and an opiate because it is an opioid receptor agonist and is derived from the opium poppy.

Fentanyl is an opioid (because it is an opioid receptor agonist) but not an opiate (it is synthetic, not a naturally occurring molecule in the opium poppy).

Opioids can be full agonists that, depending on the concentration, maximally activate opioid receptors, or partial agonists that only partially activate receptors, regardless of concentration.

- Most opioids are full agonists (morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, others).

- Buprenorphine is a partial agonist.

Opioid Regulation

In Canada, the regulatory status of opioids is addressed by the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) and the Narcotic Control Regulations.

The CDSA (2019) and its regulations provide a legal framework to make the production, sale, and possession of certain substances illegal. The regulations also outline:

- exceptions for legal sale and possession,

- who is authorized to prescribe opioids for medical purposes (physicians, nurse practitioners, dentists, etc.),

- who is authorized to dispense opioids (pharmacists),

- who is authorized to administer opioids (physicians, nurses, etc.), and

- who can possess opioids and under what circumstances (a client who has a prescription and is using opioids to treat pain, for example).

Regulated Opioids in Canada

The following is a list of opioids regulated in Canada.

- buprenorphine

- butorphanol

- codeine

- fentanyl

- hydrocodone

- hydromorphone

- meperidine

- methadone

- morphine

- normethadone

- opium

- oxycodone

- oxymorphone

- pentazocine

- tapentadol

- tramadol

In 2019, the Canadian Institute for Health Information reported that codeine was the most commonly prescribed opioid (56.1 percent) followed by oxycodone and hydromorphone (16.7 percent and 16.5 percent, respectively).

Unregulated Opioids in North America

Unregulated opioids are produced outside the regulatory system. They are also referred to as illegal, illicit, black market, or bootleg.

In addition to unregulated opioids, regulated prescription opioids can be diverted for illegal sale after illegal importation, theft (e.g., from a pharmacy, home, or individual), or being obtained via prescription but sold to others instead.

It is difficult to determine which unregulated/illegal opioids are present in Canada at any given time.

Based on law enforcement seizures, testing of biological samples of opioid users, or pilot projects that test opioid user drug samples, several unregulated synthetic opioids have been identified in North America. For example, fentanyls have been detected, including 3-methylfentanyl, carfentanil, beta-hydroxyfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, and many others.

In addition, there are synthetic unregulated opioids that are not chemically related to fentanyl, including U-47700 and AH-7921. These numbered molecules were originally developed by pharmaceutical companies but never marketed. They have since been illegally synthesized for the unregulated market.

Opioid Dosage Forms and Routes of Administration

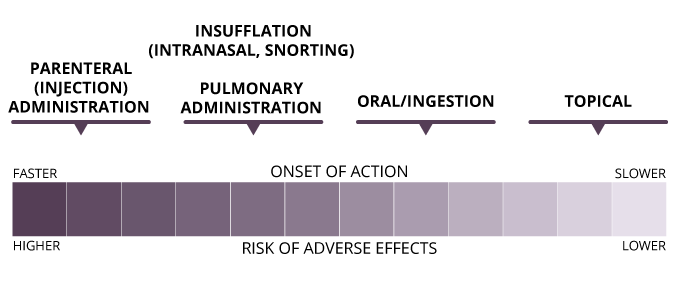

There are several ways to administer opioids. Routes of administration for opioids include the following:

- epidural injection

- insufflation/intranasal

- intramuscular injection

- intravenous injection

- oral

- pulmonary

- rectal

- subcutaneous injection

- sublingual/buccal

- topical

Generally, the effects and adverse effects of opioids occur more quickly and intensely for injected versus inhaled/nasal versus oral.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Unregulated Fentanyls and Opioid Overdose

The increase in the number of cases of opioid-induced respiratory depression/overdose and opioid-related mortality has coincided with a change in illicit opioid use, from diverted prescription opioids, particularly OxyContin, and heroin, to unregulated synthetic fentanyl and its analogues.

- OxyContin is a pharmaceutical-grade opioid, that is, each pill contains a known amount of oxycodone and each pill contains the same amount.

- Unregulated fentanyls are synthesized outside the regulated system, with no quality control.

- Unregulated fentanyls are generally more potent than pharmaceutical opioids. Small mistakes made in the supply chain, or by the user, can disproportionally increase the risk of overdose.

To learn more about opioid potency and opioid overdose, see Module 1, Topic F.

Questions

Why does the unregulated opioid U-47700 have just letters and numbers, and not have a name like morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl?

Feedback

U-47700 was developed by a pharmaceutical company (Upjohn). In the development process, companies test hundreds or thousands of molecules, so they don’t bother naming these, unless they decide to bring a drug to market.

References

Boom, M., Niesters, M., Sarton, E., Aarts, L., Smith, T. W., & Dahan, A. (2012). Non-analgesic effects of opioids: Opioid-induced respiratory depression. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 18, 5994–6004.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2019). Opioid prescribing in Canada—How are practices changing? https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/opioid-prescribing-canada-trends-en-web.pdf

Brunton, L. L., Hilal-Dandan, R., & Knollmann, B. C. (2018). Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (13 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2019). Opioid prescribing in Canada: How are practices changing?. Ottawa, ON: CIHI

Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, SC 1996, c 19. Government of Canada, Justice Laws Website. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-38.8/FullText.html

Franco F. (2018). Childhood abuse, complex trauma and epigenetics. PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/lib/childhood-abuse-complex-trauma-and-epigenetics/

Health Canada. (2018). Opioids list. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/reports-publications/medeffect-canada/list-opioids.html

Health Canada. (2019). Canada’s opioid crisis. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/canada-opioid-crisis.pdf

Katzung, B. G. (2018). Basic and clinical pharmacology (14 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Macy, B. (2018). Dopesick: Dealers, doctors, and the drug company that addicted America. Little, Brown, and Company.

Narcotic Control Regulations, CRC, c 1041. Government of Canada, Justice Laws Website. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._1041/FullText.html

Sofalyi, S., Lavins, E. S., Brooker, I. T., Kaspar, C. K., Kucmanic, J., Mazzola, C. D., Mitchell-Mata, C. L., Clyde, C. L., Ricco, R. N., Appolonio, L. G., Goggin, C., Marshall, B., Moore, D., & Gilson, T. P. Unique structural/stereo-isomer and isobar analysis of novel fentanyl analogues in postmortem and DUID whole blood by UHPLC-MS-MS. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 43, 673–687.

Solimini, R., Pichini, S., Pacifici, R., Busardo, F. P., & Giorgetti, R. (2018). Pharmacotoxicology of non-fentanyl derived new synthetic opioids. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, 654.