Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe some of the barriers that can limit an individual’s ability to seek treatment.

- Describe some of the barriers that may impact treatment retention and success.

- Describe some of the facilitators that support people in treatment.

Key Concepts

- Barriers to treatment stem from many domains, including society, culture, social determinants of health, and clinical and interpersonal areas.

- Taking the time to understand the barriers specific to individuals encourages positive treatment outcomes.

- People face many barriers when seeking treatment or remaining in treatment, ranging from health and social service provider bias and prejudice to structural inequities.

- Facilitators for treatment range from individual traits of the health and social service provider to organizational policies and program delivery modalities.

Potential Barriers to Treatment

Many potential barriers exist that can limit the involvement of persons using opioids in their care. Barriers also exist that prevent people from initially entering treatment or prevent those who do enter treatment from continuing it. These barriers range from interpersonal (communication, language) to structural (how services are designed and delivered). Some of these barriers and their impacts are identified and discussed below.

Barrier #1: Language

Language can function as either a barrier or a facilitator to entering or staying in treatment. For example:

- The use of medical terminology can remove the human element and medicalize the process for the individual.

- Offering service in a language that is not comfortable for the client can make the experience uncomfortable and confusing.

Medical and other unfamiliar terminology can distance the health and social service provider from the person’s lived experience, jeopardizing the critical issue of trust between the provider and the client.

The individual may feel intimidated or embarrassed to ask the health and social service provider questions, missing the opportunity to receive well-explained instructions on treatment.

Barrier #2: Health Literacy

The World Health Organization (n.d.) defines health literacy “as the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health. Health Literacy means more than being able to read pamphlets and successfully make appointments. By improving people's access to health information and their capacity to use it effectively, health literacy is critical to empowerment.”

The individual may feel intimidated or embarrassed to ask the health and social service provider questions, missing the opportunity to receive well-explained instructions on treatment.

For example, the ability to read and understand consent, admission criteria to different treatment options, and pharmacological instructions, and to transfer this information into behaviour can be a barrier to some individuals.

Treatment and counselling programs are predominately delivered in English, which ignores the diversity of those using substances. Degan et al. (2019) conducted a study in Australia of 298 participants in a residential treatment program and found that low to moderate health literacy levels were common among those in the program.

Participants with lower levels of health literacy also experience less social support in their home environment outside treatment, as well as a lower quality of life and higher levels of psychological distress.

Watch this short video from Vancouver Coastal Health on what health literacy is and why it is important. Although not specific to opioid use and treatment, the concepts are transferable:

According to Chiarelli and Edwards (2006), 1/7 of all Canadians are at the lowest level of literacy. Low health literacy can lead to improper use of prescription drugs, inadequate treatment, and failure to follow instructions.

Individuals with low health literacy have more frequent and longer hospitalizations and greater difficulties managing chronic health conditions, and lack necessary skills to navigate the health care resources.

Barrier #3: Racial and Ethnic Differences

Domestic and international studies have shown a greater intersectionality of the social determinants of health and treatment options for racial and ethnic groups.

Black people, Hispanics, Indigenous Peoples, and refugees share many of the same barriers to accessing treatment, including unstable housing, higher levels of psychosocial stressors and trauma, racism, and culturally insensitive treatment.

Stahler and Mennis (2018) surveyed individuals enrolled in opioid treatment programs in 42 U.S. metropolitan cities to determinate if racial and ethnic differences existed regarding treatment completion.

The authors found that Black and Hispanic people experienced lower treatment utilization rates, greater barriers to receiving treatment, and poorer outcomes, including treatment completion, compared to white clients.

Similarly, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2017) reported that members of ethnic minorities, migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers who have substance use problems are particularly vulnerable to barriers in accessing needed treatment services. Studies conducted by the Centre suggest that race/ethnicity also interacts with other factors, such as drug of choice and treatment modality, to produce disparities in treatment completion.

Barrier #4: Health and Social Service Provider Characteristics

Personal characteristics do make a difference in facilitating a climate of respect, trust, and collaboration.

A study of 85 regular daily or almost daily opioid users were asked what characteristics of the staff were seen as barriers when they are in treatment. The first issue identified was “better treatment by staff” and concerns about being judged.

Clients also stated that health and social service providers focused too much on adherence to “rules” and the results of urine drug testing rather than on understanding the nature of addiction and on clients as individuals (Deering et al., 2011).

Providers who are perceived as trustworthy, informed, caring, and respectful were associated with higher retention rates in programs.

For example, in a study of 105 individuals in a community-based opioid treatment program, Teruya et al. (2014) found that clients used words such as "nice," "caring," and "respectful" to describe providers who were particularly impactful in their recovery.

In addition to personality traits of the health and social service provider, Krahn et al. (2006) found that provider sensitivity to treatment barriers (political, attitudinal, or physical) was equally important when creating individual treatment plans.

Kantian logic tells us “we do not see things as they are but as we are” (Halwani, 2004). The lack of race representation among service providers plays a significant role in both access to, and delivery of services.

Barrier #5: Stigma and Beliefs

See Module 4, Topic D for more information.

Stigma examples

Some stigmas might include a lack of anonymity if living in a smaller community or town, and concerns around confidentiality if living and being treated in a rural or smaller town or community.

"People struggling with both substance use and homelessness experience overlapping barriers to accessing care, including stigma related to care itself." (Magwood et al. 2020)

Sutter et al. (2017) found that women may be concerned about losing custody of their children if it were discovered that they are drug-dependent, which is associated with a societal stigma related to mothers and drug use.

Belief examples

The client-held perspective may be that medication assisted treatment (MAT) is "inconsistent with being drug-free, as promoted in some (but not all) 12-step programs or by peers or other counsellors, and therefore MAT is not an acceptable treatment." (Uebelacker et al. 2016)

For example, some people view methadone treatment as switching one drug for another.

Personal "beliefs that treatment will have a positive impact on the person’s life (i.e., be efficacious) predict the likelihood of engaging in long-term substance use treatment after acute detoxification." (Uebelacker et al. 2016)

Barrier #6: Format of Treatment Program

Programs may offer only opioid treatment programs and not be inclusive of the high prevalence of concurrent disorders (anxiety and depression).

Sutter et al. (2017) found women are less likely to seek treatment because programs do not meet their specific needs (past sexual abuse and violence).

Relapse prevention programs recommend addressing both issues concurrently.

There is a need to allow for easier re-entry into programs if the person should leave prematurely.

Barrier #7: Social Determinants of Health

For more information, see the Canadian Mental Health Association’s work on Social Determinants of Health.

Experiencing homelessness and using more than one substance at admission were associated with a decreased likelihood of treatment completion (Magwood et al., 2020).

Without stable housing, individuals often experience barriers to accessing and following treatment recommendations for substance use disorders.

Individuals living in rural areas have less access to programs—this may require a relocation, which introduces new issues or stresses.

Inpatient or residential programs can impact the financial stability of a family if primary wage earner is not employed (fear of job loss).

In one study, transportation was cited by 65 percent of participants as a barrier to accessing treatment (Krahn et al., 2006).

Persons using wheelchairs encounter multiple and intersecting barriers, including attitudinal, communicative, architectural, and discriminatory policies in the treatment of persons with disabilities (Krahn et al., 2006).

Individual Treatment Facilitators

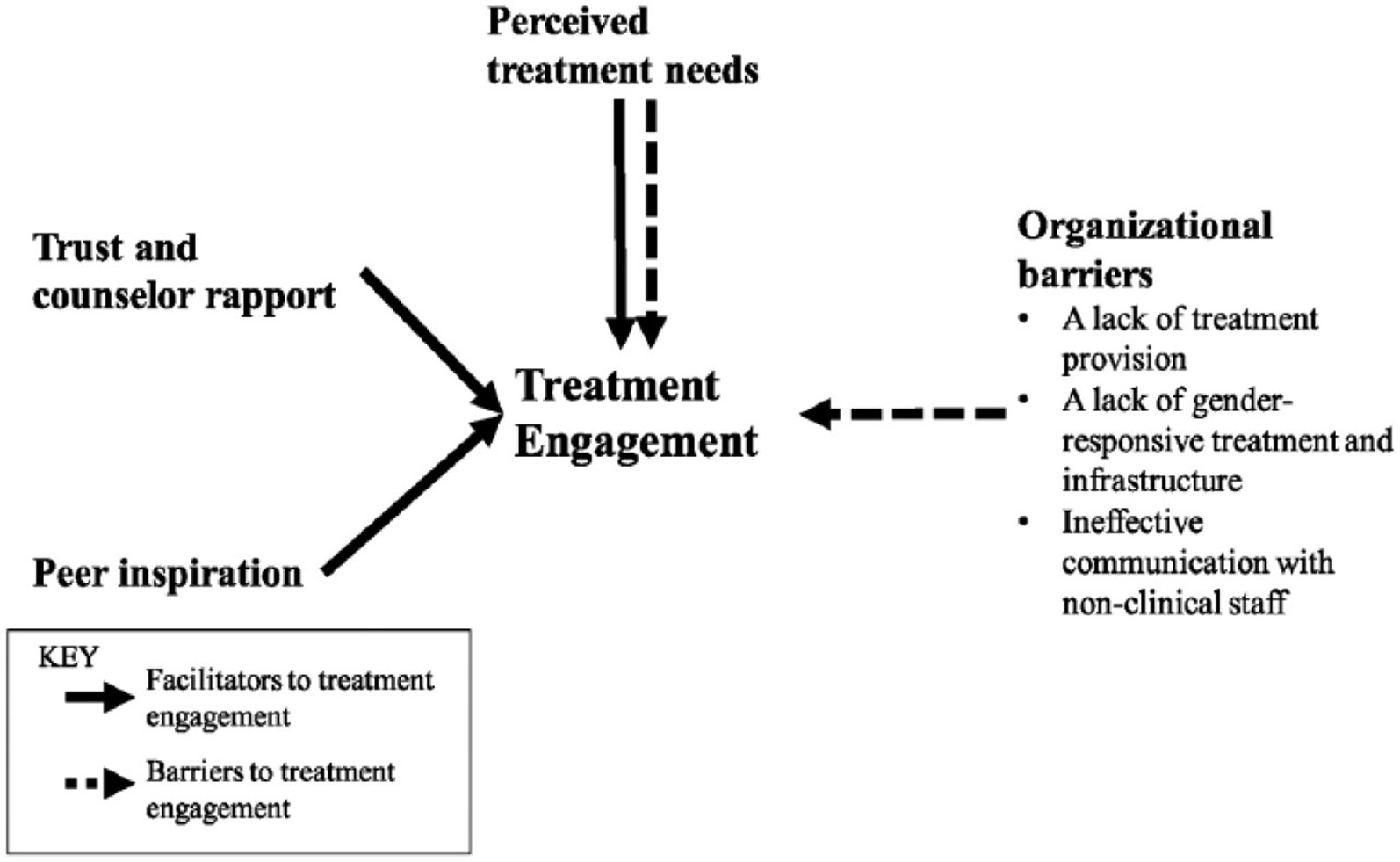

In a study of 60 people who were enrolled in a short-term substance treatment program, Yang et al. (2018) identified key themes regarding what they considered to be facilitators and barriers.

- Facilitator themes included an understanding of treatment needs, trust and counsellor rapport, peer inspiration, and organizational factors (shown below).

- Barrier themes included perceived treatment needs and organizational factors.

Barriers and Facilitators to Treatment

Peer inspiration, trust and counselor rapport and perceived treatment needs are facilitators to treatment engagement. Organizational barriers as well as a lack of perceived treatment needs can be barriers to treatment engagement. See Table 1 below for more details.

Yang et al. (2018)

| Barrier/Facilitator | Description |

|---|---|

| Understanding of treatment needs | Understanding the client’s readiness for treatment, adopting client-centred counselling techniques to discuss treatment needs, developing individualized treatment plans, and cultivating motivation |

| Trust and rapport | Individual counsellor traits such as empathy and care for the entire person as compared to just the presenting substance issue |

| Peer inspiration | Groups where others’ stories are shared for inspiration |

| Organizational factors | Correlation between client expectation and actual treatment programs, transparency of treatment program, acknowledgement of the impact of trauma and how it relates to substance treatment |

Yang et al. (2018)

Questions

References

Arndt, S., Acion, L., & White, K. (2013). How the states stack up: Disparities in substance abuse outpatient treatment completion rates for minorities. Drug Alcohol Dependency, 132, 547–554.

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2014). Health literacy. Retrieved from http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/perf_stands/healthy_living/background/health_literacy.htm

Chiarelli, L., & Edwards, P. (2006). Building healthy public policy. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 97(Suppl. 3), 7–42.

Degan, T. J., Kelly, P. J., Robinson, L. D., & Deane, F. P. (2019). Health literacy in substance use disorder treatment: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 96, 46–52. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.10.009

Deering, D., Sheridan, J., Sellman, J., Adamson, S., Pooley, S., Robertson, R., & Henderson, C. (2011). Consumer and treatment provider perspectives on reducing barriers to opioid substitution treatment and improving treatment attractiveness. Addictive Behaviors, 36(6), 636–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2017). Health and social responses to drug problems: A European guide. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/6343/TI_PUBPDF_TD0117699ENN_PDFWEB_20171009153649.pdf

Halwani, S. (2004). Racial inequality in access to health care services. Ontario Human Rights Commission. www.ohrc.on.ca/en/race-policy-dialogue-papers/racial-inequality-access-health-care-services

Krahn, G., Farrell, N., Gabriel, R., & Deck, D. (2006). Access barriers to substance abuse treatment for persons with disabilities: An exploratory study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31(4), 375–384.

Magwood, O., Salvalaggio, G., Beder, M., Kendall, C., Kpade, V., Daghmach, W., Habonimana, G., Marshall, Z., Snyder, E., O'Shea, T., Lennox, R., Hsu, H., Tugwell, P., & Pottie, K. (2020). The effectiveness of substance use interventions for homeless and vulnerably housed persons: A systematic review of systematic reviews on supervised consumption facilities, managed alcohol programs, and pharmacological agents for opioid use disorder. PloS One, 15(1), e0227298. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227298

McKetin, R., & Kelly, E. (2007). Socio-demographic factors associated with methamphetamine treatment contact among dependent methamphetamine users in Sydney, Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26, 161–168.

Palepu, A., Gadermann, A., Hubley, A. M., Farrell, S., Gogosis, E., Aubry, T., & Wang, S. W. (2013). Substance use and access to health care and addiction treatment among homeless and vulnerably housed persons in three Canadian cities. PLoS One, 8(10), e75133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075133

Pelissier, B., & Jones, N. (2005). A review of gender differences among substance abusers. Crime & Delinquency, 51(3), 343–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128704270218

Rapp, R. C., Xu, J., Carr, C. A., Lane, D. T., Wang, J., & Carlson, R. (2006). Treatment barriers identified by substance abusers assessed at a centralized intake unit. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 30(3), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.01.002

Stahler, G. J., & Mennis, J. (2018). Treatment outcome disparities for opioid users: Are there racial and ethnic differences in treatment completion across large US metropolitan areas? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.006

Sutter, B. Gopman, S., & Leeman, L. (2017). Patient-centred care to address barriers for pregnant women with opioid dependence. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 44(1), 95–107.

Teruya, C., Schwartz, R. P., Mitchell, S. G., Hasson, A. L., Thomas, C., Buoncristiani, S. H., Hser, Y.-I., Wiest, K., Cohen, A. J., Glick, N., Jacobs, P., McLaughlin, P., & Ling, W. (2014). Patient perspectives on buprenorphine/naloxone: A qualitative study of retention during the starting treatment with agonist replacement therapies (START) study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(5), 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2014.921743

Uebelacker, L. A., Bailey, G., Herman, D., Anderson, B., & Stein, M. (2016). Patients' beliefs about medications are associated with stated preference for methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, or no medication-assisted therapy following inpatient opioid detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 66, 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.02.009

Vancouver Costal Health. (2014, June 19). Health literacy basics for health professionals [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8w9kdcRgsI

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Health literacy and health behaviour. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/track2/en/

Yang, Y., Perkins, D., & Stearns, A. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to treatment engagement among clients in inpatient substance abuse treatment. Qualitative Health Research, 28(9), 1474–1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318771005