Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Review the influence of the political atmosphere in the opioid crisis.

- Discuss external factors influencing increased addiction rates among Canadians.

- Describe the social and cultural impact of the opioid crisis.

- Understand trauma-informed practice and how to build resilience.

Key Concepts

- Multiple contexts, social and structural determinants of health, stigma, and bias can impact persons using opioids

- understanding these contexts is crucial to working effectively with people who use opioids.

- The continued criminalization of drugs and drug use contributes to the stigma of individuals who use drugs, which can delay widespread implementation of evidence-based harm reduction strategies.

- Opioid use and opioid-related harms can affect communities in different ways.

- Indigenous groups (including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) have been heavily and disproportionately impacted by opioid-related harm.

- First Nations persons are five times as likely as their non–First Nations counterparts to experience an opioid-related overdose event and three times as likely to die from an opioid-related overdose.

- Opioid misuse might be an attempt to cope with a past traumatic event.

- Creating resilience in communities would help to ensure that people with substance use disorders have the same opportunities as others to succeed.

Political Atmosphere And Criminalization Of Opioid Use

- The continued criminalization of drugs and drug use perpetuates stigma surrounding individuals who use drugs, which can delay widespread implementation of evidence-based harm reduction strategies.

- Stigma can prevent persons who use drugs from getting the help they need and create barriers to accessing vital health and social services.

- Public health policies and regulations can also cause delays in addressing urgent opioid harms. For example, in the recent past, numerous unsanctioned supervised consumption sites had to be opened across cities because of regulations preventing the sites’ implementation (Kerr et al. 2017).

- Arresting individuals who are using drugs might take away valuable resources needed to address the high volume of overdoses through prevention, harm reduction, and treatment services.

- Example: Portugal’s national strategy on decriminalization has led to reductions in the social harms of drug use, including less demand on criminal justice resources (Hughes & Stevens, 2010).

- Many communities are starting to view harmful substance use as a chronic health issue rather than a criminal justice issue.

- Bill C-37 supported the scaling up of safer consumption sites across Canada.

- Read a letter from Canadian Minister of Health, Patti Hajdu from August 2020 to the Provincial and Territorial Ministers of Health and regulatory colleges encouraging action to improve options for persons who use drugs.

- Some researchers and policymakers suggest decriminalization of drugs to effectively address the opioid crisis, along with healthy drug policies and regulations (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2018).

- Individual jurisdictions are beginning to advocate for drug strategies that decriminalize persons that use drugs. Example: Read a statement from the Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox & Addington Community Drug Strategy Advisory Committee.

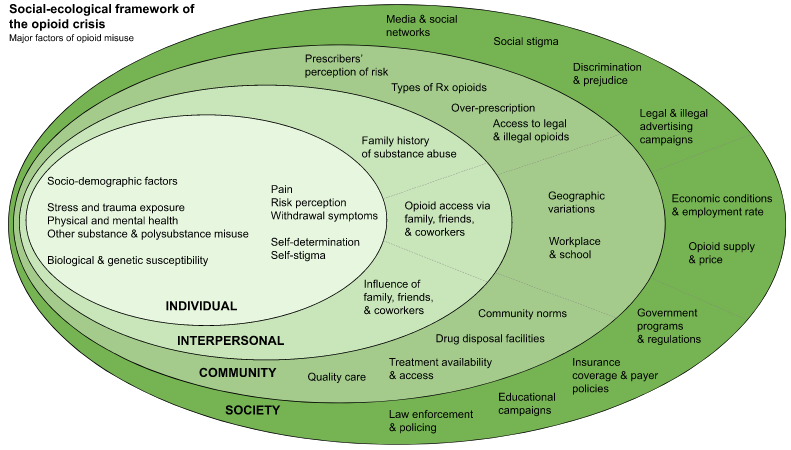

Figure 1. The Socio-ecological Framework (Jalali et al., 2020)

Jalali et al. (2020) Propose a Socio-ecological Framework that includes Individual, Interpersonal Community and Society to explain and illustrate the interconnection of risk factors for opioid misuse.

Impact Of Opioid Use On Indigenous Populations

- Indigenous Peoples (including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) have been heavily impacted by opioid-related harm and disproportionately affected by substance use.

- First Nations people are five times as likely as their non–First Nations counterparts to experience an opioid-related overdose event and three times as likely to die from an opioid-related overdose (Belzak & Halverson, 2018).

- In British Columbia, Indigenous women experience eight times as many overdose events and five times as many deaths from overdose as non‐Indigenous women, and Indigenous men experienced three times as many overdose events and deaths than non‐Indigenous men (First Nations Health Authority, 2017).

- Indigenous communities that are more remote and rural are struggling less with opioid problems than those in urban centres.

- First Nations people are twice as likely to be prescribed an opioid as non–First Nations individuals, and tend to be at least five years younger than their non–First Nations counterparts when first prescribed opioids (Belzak, & Halverson, 2018).

- The disparity of opioid use problems seen in these communities is understood to be rooted in a history of colonization and racism causing trauma, loss, poverty, and family separation, which had seismic and multi‐generational impacts on the mental health and well-being of First Nations persons.

Trauma-Informed Practice

Trauma has been described as resulting from three ‘E’s (SAMSHA, 2014):

- Events: actual or extreme threat of physical or psychological harm or severe neglect in the case of children affecting healthy development

- Experience: persons experience of the event as physically or emotionally harming or life threatening

- Effects: lasting effects on a person’s functioning and multidimensional well-being

Experience with one or more traumatic events can alter an individual’s capacity to cope. Trauma can include, but is not limited to, traumatic early life experiences, child abuse, neglect, witnessing or experiencing violence, sexual abuse, war, natural disaster, sudden unexpected loss, feeling life is out of one’s control, poverty, having a life-threatening illness, and intergenerational events.

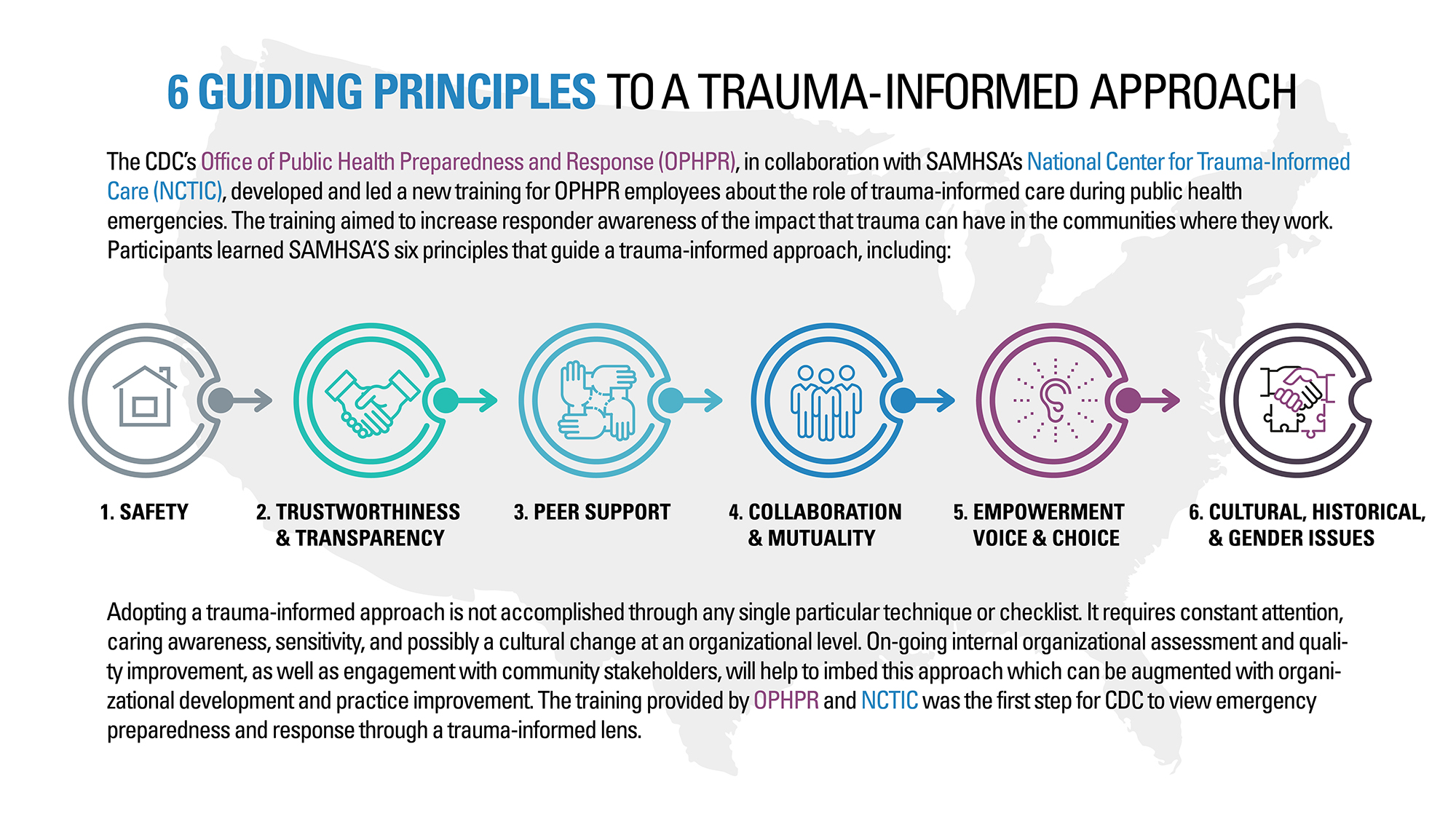

- Harmful opioid use may be an attempt to cope with a past traumatic event (Center for Preparedness and Response, 2020; see Figure 3).

- Multidimensional assessment should incorporate an awareness that the client may have experienced trauma.

- A key question to consider is What happened to this person?

Adopting a Trauma-informed approach to care is essential to care – particularly in the context of opioid use and opioid use disorders. A trauma-informed approach Realizes the impact of trauma, Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma, Responds on a multi-system level and Resists re-traumatization (SAMSHA, 2014).

- Trauma-informed practice can address harmful opioid use by:

- improving access and engagement with health care and social services

- creating opportunities for individuals to heal from trauma

- supporting the development of wellness skills and pain management skills to help prevent opioid misuse and dependence

- improving safety of service providers to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout

- Providers must understand that negative reactions (such as rage, treatment refusal, mistrust, fear) are common for those who have experienced trauma.

- Download the Trauma-Informed Care Resources Guide from the US Crisis Prevention Institute.

Principles For Trauma-Informed Practice

Figure 3:

Source: U.S. Center for Preparedness and Response, 2020

Purkey, Patel and Phillips (2018) Contextualize the principles of Trauma Informed Care presented in Figure 3 to primary care practice in a 5 step process:

Step 1: Bear witness to the persons experience of trauma

Step 2: Help persons feel they are in a safe space and recognize their need for physical and emotional safety

Step 3: Include persons in the healing process

Step 4: Believe in the person’s strength and resilience

Step 5: Incorporate processes that are sensitive to a person’s culture, ethnicity, and personal and social identity.

To read more about this contextualization, consider retrieving the article.

Further reading: Nathoo, T., Poole, N. and Schmidt, R. (2018). Trauma-Informed Practice and the Opioid Crisis: A Discussion Guide for Health Care and Social Service Providers. Vancouver, BC: Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health.

Opioid Use And Building Resilience

- Health and social service providers should understand that opioid misuse and addiction might be an attempt to cope with a past traumatic event.

- The focus should be on strengths rather than deficits and providing opportunities for clients to build skills (coping skills, self-regulation skills such as mindfulness, and how to recognize triggers):

- acknowledging the resilience of individuals who experienced trauma

- increasing social, emotional, and resiliency skills

- supporting grounding skills and coping skills for managing trauma (recognizing triggers, calming, centring, staying present-minded)

- promoting pain management skills (relaxation techniques, mindfulness, yoga, physical exercise, breathing techniques)

- developing attachment and relational skills

- creating safety-plans and goal setting

- Creating resilience in communities helps to ensure people with substance use disorders have opportunities to succeed.

- Social determinants of health (education, employment, housing, and income) are highly correlated with individual sense of competence and control.

- These influence people’s ability to cope with their environment.

- Housing with supports, including health services, income support, social support, and the securing of employment, can immensely help individuals with substance use issues.

- Investing in community resources, such as enhancing community-based services and peer support services, and improving engagement with the primary care sector can create more resilient communities.

- Policies and regulations that promote health, affordable housing, accessible employment resources, and income support are important.

- Agencies should be required to have people with lived experience and family members as voting members on boards to develop inclusive community tools and resources.

- The implementation of a shared and stepped care model should be supported.

Tools available to conduct screening and assessment for opioid use

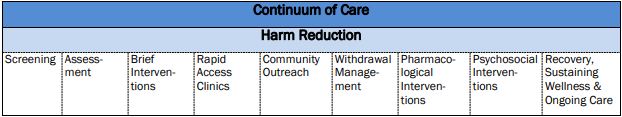

- Continuum of care: Screening and assessment are parts of the recovery-oriented continuum of care for those suffering from opioid use disorder (see Figure 4).

- The continuum of care represents a range of services that should be available to individuals experiencing or at risk for experiencing harms from opioid use (Taha, 2018).

- Although presented as discrete categories, many of the continuum components overlap in practice (e.g., screening and assessment) and are most effective when used together.

- Pathways through the continuum are not necessarily meant to be linear. Some individuals might use all components of the continuum whereas others might not, and some might revisit different components as needed (Taha, 2018).

Figure 4. Continuum of care

- Assessment: Assessment can allow for the identification of an opioid use disorder and co-occurring conditions, determines the severity, and indicates the intensity of treatment to be considered (Taha, 2018).

- The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) is the most recognized criteria to establish a diagnosis of opioid use disorder.

- Assessment should include concurrent disorders and physical health concerns, and an examination of recovery capital, the resources an individual has to support them through their journey. Treatment should then be designed to build and strengthen recovery capital.

- Assessment should also include collaborative care planning with the individual seeking treatment. It should be repeated throughout treatment to ensure services are meeting the individual’s changing needs.

- There are multiple assessment tools, including the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), a structured interview that assesses an individual’s functioning or the severity of problems an individual with an opioid use disorder is experiencing in the medical, employment, legal, social, psychological and substance use components of their lives.

- Assessment of individuals living with chronic pain

- The Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT) assesses analgesia, activities of daily living, adverse effects, and aberrant drug related behaviours.

Conducting an assessment for individuals from different backgrounds

- An individual’s cultural background affects their coping style, social supports, stigma of substance use disorders, and help-seeking behaviour.

- Verbal communication is critical in diagnosis of substance use disorders.

- About 23 percent of African Americans and 15 percent of Latinos felt that they would have received better treatment if they were another race. Only 6 percent of Caucasians feel this way (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2006).

- Counsellors might feel their own social values are the norm.

- Most intensive outpatient treatment counsellors are White and from a Western culture.

- Despite the heterogeneity among ethnic or racial groups, treatment providers sometimes apply stereotypes to individual members of a given group.

- It’s important to ask individuals about best practices for culturally appropriate care. For example, something that can seem minor to the provider might be important to the People in some cultures will take offence to being addressed by their first names as they see being treated with dignity and respect as extremely important.

- Some people have a mistrust of authority or fear of government that inhibits them from accessing services.

- Clients may believe that substance use disorder negatively affects the whole family lineage, including affecting marriage and economic prospects.

- Clinicians who want to reach out to foreign-born clients should become more knowledgeable about the client’s history and experiences (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2006).

- There are some things providers can do to reduce barriers for clients from different cultural backgrounds:

- If possible, providing treatment in the client’s first language may reduce barriers for that service user.

- A culturally sensitive program should ask clients about dietary preferences, special holidays, and religious customs.

- Clinicians should assess their program’s policies that might be a barrier to a specific culture.

- Some people had to leave behind family and friends to move to a new country. They may benefit from friend and family involvement in care.

- Written materials should be at an appropriate reading level, there should be strong outreach to increase awareness, and counsellors should be hired from diverse populations.

- Partnering with other organizations, like those that have English as a second language courses, could benefit clients.

- Providing meals may entice clients and induce them to stay (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2006).

Stop And Think

Opioid use and opioid-related harms can affect different communities and demographics in different ways. For example:

- Unregulated opioid use is illegal.

- Most opioid overdoses in Canada occur in males, ages 30–39.

- First Nations people are five times as likely to experience an overdose.

- History of trauma is associated with an increase likelihood of opioid use.

- Lack of social supports, including housing, can impact resiliency.

The examples above can reinforce attitudes and beliefs about opioid use for clients who can identify with one or more of them.

If you were to encounter an individual who was affected by the opioid crisis, reflect on how your knowledge about opioid use could positively inform your interaction and reflect on how your biases might negatively impact your interaction with that individual.

References

Belzak, L., & Halverson, J. (2018). Evidence synthesis—The opioid crisis in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 38(6), 224.

British Columbia Coroners Service. (2019). Fentanyl-detected suspected illicit drug toxicity deaths, 2012–2019. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/fentanyl-detected-overdose.pdf

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl. 2), 19–31.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2018). Canadian substance use costs and harms 2007–2014. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CSUCH-Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs-Harms-Report-2018-en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). Opioid-related harms in Canada.

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2018). Care not corrections: Relieving the opioid crisis in Canada. https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CMHA-Opioid-Policy-Full-Report_Final_EN.pdf

Canadian Psychological Association. (2019). Recommendations for addressing the opioid crisis in Canada. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Task_Forces/OpioidTaskforceReport_June2019.pdf

Emerson, B., Haden, M., Kendall, P., Mathias, R., & Robert Parker, R. (2005). A public health approach to drug control in Canada. Health Officers Council of British Columbia.

Center for Preparedness and Response. (2020). 6 guiding principles to a trauma-informed approach. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/infographics/00_docs/TRAINING_EMERGENCY_RESPONDERS_FINAL.pdf

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2006). Addressing diverse populations in intensive outpatient treatment. In Substance abuse: Clinical issues in intensive outpatient treatment (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 47) (Chapter 10). U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64093/

First Nations Health Authority. (2017). Overdose data and First Nations in BC: Preliminary findings. http://www.fnha.ca/newsContent/Documents/FNHA_OverdoseDataAndFirstNationsInBC_PreliminaryFindings_FinalWeb.pdf

Fischer, B., & Argento, E. (2012). Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: A review. Pain Physician, 15(3 Suppl.), ES191–E203.

Gomes, T., Greaves, S., Martins, D., Bandola, D., Tadrous, M., Singh, S., Juurlink, D., Mamdani, M., Paterson, P., Ebejer, T., May, D., & Quercia, J. (2017). Latest trends in opioid-related deaths in Ontario: 1991 to 2015. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. https://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ODPRN-Report_Latest-trends-in-opioid-related-deaths.pdf

Hadland, S. E., Wharam, J. F., Schuster, M. A., Zhang, F., Samet, J. H., & Larochelle, M. R. (2017). Trends in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone for opioid use disorder among adolescents and young adults, 2001–2014. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(8), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0745

Hall, W. J., Chapman, M. V., Lee, K. M., Merino, Y. M., Thomas, T. W., Payne, B. K., Eng, E., Day, S. H., & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76.

Health Canada. (2017). Baseline survey on opioid awareness, knowledge and behaviors for public education research report (Unpublished report). Prepared by Earnscliffe Strategy Group for Health Canada.

Health Canada. (2018). Synthetic opioids/novel psychoactive substances: Impact on Canada’s opioid crisis. https://www.who.int/medicines/news/2018/10Canada.pdf

Hughes, C. E., and Stevens, A. (2010). What can we learn from the Portuguese decriminalization of illicit drugs? British Journal of Criminology.

Kerr, T., Mitra, S., Kennedy, M.C., Mcneil, R., 2017. Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. Harm Reduction Journal 14.

King, N. B., Fraser, V., Boikos, C., Richardson, R., & Harper, S. (2014). Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), e32–e42.

Jalali, M.S., Botticelli, M., Hwang, R.C., Koh, H.K., Mchugh, R.K., 2020. The opioid crisis: a contextual, social-ecological framework. Health Research Policy and Systems 18.

Leshner, A., & Mancher, M. (Eds.). (2019). Barriers to broader use of medications to treat opioid use disorder. In Medications for opioid use disorders save lives (pp. 127–135). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538936/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK538936.pdf

Nathoo, T., Poole, N., & Schmidt, R. (2018). Trauma informed practice and the opioid crisis: A discussion guide for health care and social service providers. Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health.

MacKay, R., & Tiedemann, M. (2015). Bill C-70: An Act to amend the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and to make related amendments to other Acts. Library of Parliament.

McMaster, G. (2019). Opioid crisis has cost Canada nearly $5 billion in lost productivity, U of A student finds. Folio. https://www.folio.ca/opioid-crisis-has-cost-canada-nearly-5-billion-in-lost-productivity-u-of-a-student-finds/

Oliver, J., Coggins, C., Compton, P., Hagan, S., Matteliano, D., Stanton, M., St Marie, B., Strobbe, S., Turner, H. N., & American Society for Pain Management Nursing. (2012). American Society for Pain Management nursing position statement: Pain management in patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 23(3), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0b013e318271c123

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). (2017). Opioid-related morbidity and mortality in Ontario. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. http://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/dataandanaly4cs/pages/opioid.aspx

Pain & Policy Studies Group, University of Wisconsin. (n.d.). Canada: Opioid consumption in morphine equivalence (ME), mg per person. http://www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/country/profile/Canada

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2018). Chief Public Health Officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada, 2018: Preventing problematic substance use in youth. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/2018-preventing-problematic-substance-use-youth/2018-preventing-problematic-substance-use-youth.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Government of Canada supports efforts to better understand how substance use affects Indigenous communities [News release]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2019/07/government-of-canada-supports-efforts-to-better-understand-how-substance-use-affects-indigenous-communities.html

Purkey,E., Patel, R., & Phillips, S. (2018). Trauma-informed care: Better care for everyone.

Canadian Family Physician, 64 (3) 170-172.

SAMSHA (2014). Concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Retrieved from: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884

Sherlock T. (2018). Could decriminalization be the answer to B.C.’s overdose crisis? National Observer. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2018/10/03/opinion/could-decriminalization-be-answer-bcs-overdose-crisis

Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. (2019). National report: Opioid-related harms in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids

Stahler, G. J., & Mennis, J. (2018). Treatment outcome disparities for opioid users: Are there racial and ethnic differences in treatment completion across large US metropolitan areas? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.006

Taha, S. (2018). Best practices across the continuum of care for treatment of opioid use disorder. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

Taha, S., Maloney-Hall, B., & Buxton, J. (2019). Lessons learned from the opioid crisis across the pillars of the Canadian drugs and substances strategy. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 14(1), 1–10.

Tu, H., & Cole, K. (2017). Respectful language and stigma regarding people who use substances. Provincial Health Services Authority, BC Centre for Disease Control, Toward the Heart. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/respectful-language-and-stigma-final_244.pdf

U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. (2016). Health care systems and substance use disorders. In Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General's report on alcohol, drugs, and health (pp. 244–314). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.