Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Discuss the integration of person-centred, trauma-informed and culturally humble approaches and the biopsychosocial model in the care of persons using opioids and persons with an opioid use disorder

- Review examples of special considerations related to age and indigeneity in the care of persons using opioids and persons with opioid use disorders

Key Concepts

- Contextualization of the care of persons using opioids and persons with opioid use disorders must be based on trauma-informed, person-centred and culturally humble care theory must consider the biopsychosocial model at all levels.

- Cultural factors can influence illness in a number of ways including defining what is regarded as normal and abnormal, determining the cause of illness, influencing the decision-making control in health care settings, and changing health-seeking behaviour.

- Cultural humility is an open and supportive approach where providers are reflective and subject their own preconceptions to critique

- Providers must be sensitive to care considerations relating to age and indigeneity and individual cultural needs

Supportive Approaches To Caring For Persons Using Opioids And Persons With An Opioid Use Disorder

Establishing a person-centred and trusting dialogue with the client is key to a successful and meaningful clinical relationship, especially in context of complex chronic care. Bringing together a trauma-informed and culturally humble approach within person-centred practice ensures individualized and supportive in the care of persons using opioids and persons with an opioid use disorder. Promoting a structure that is based on the Biopsychosocial Model helps to make care integrated.

Person-centred practice

Person centred practice is an approach that promotes putting people and families at the centre of their care and relating to them as partners and experts in their own experience: it is consistent with the philosophy of doing things with people rather than to them.

Person-centred practice includes:

- respecting people’s values;

- taking into account people’s preferences and expressed needs;

- coordinating and integrating care;

- working together to make sure there is good communication, information and education;

- making sure people are physically comfortable and safe;

- providing emotional support;

- involving family and friends where able;

- making sure there is continuity between and within services; and,

- making sure people have access to appropriate care when they need it

Cultural Humility

Cultural humility is an approach to care that fits well in the context of trauma-informed and person-centred practice that challenges providers to adopt continuous reflection and critique (Foronda et al., 2016). Providers that are culturally humble learn and work with persons rather than apply uncontextualized information about a culture, assuming the approach is appropriate to the individual.

Cultural practices and interventions take a holistic approach and can bridge gaps in treatments originating out of biomedical-based medicine (Leyland et. al., 2016)

- Many providers lack knowledge about cultural interventions, their role, their efficacy, and how they can work in collaboration with biomedical treatments. Health professional education programs offer limited information and discussion of such practices (Linklater, 2014)

The Biopsychosocial Model

Shifting from the traditional biomedical model that includes biological, psychological, and social factors unique to an individual that interact to influence the development and experience of symptoms and conditions The Biopsychosocial model was originally proposedly by Engel in 1977 to expand interventions and assessment beyond the physical realm.

- The Biopsychosocial model has been contextualized for pain by including the prevention, assessment, and management of pain (Bevers et al., 2016)

- The revision encompasses the whole person and their experience of pain, including the impact of environmental, emotional, and spiritual factors

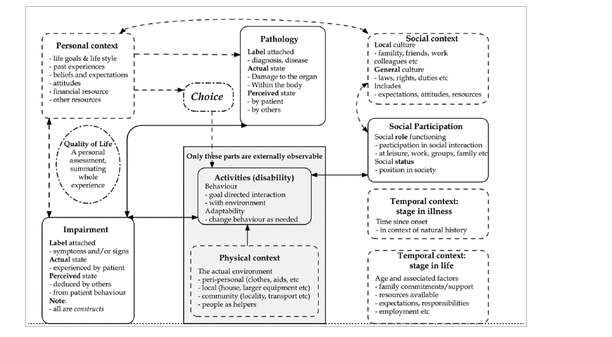

- Wade and Halligan (2017) revisited the original biopsychosocial model through the lens of chronic disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Biopsychosocial model revisited (Wade & Halligan, 2017)

Age, Culture and Indigeneity

Some groups of persons require specific approaches to care and the prevention of risk and experience of opioid-related harm. Providers must be alert to the need for contextual considerations for any group but particularly for youth and older adults and indigenous persons.

- Adolescents and youth [Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA), 2015]

- Developmentally and culturally appropriate care that is safe, low barrier, youth‐centred, collaborative, flexible, evidence‐based, and trauma‐informed, and that integrates harm reduction and treatment for concurrent mental health disorders

- Guidelines recommend psychosocial and psychological treatments should be offered to youth struggling with opioid use problems although Interventions should be tailored to the unique needs of youth and not presume a “one‐size-fits-all” approach.

- Developmentally and culturally appropriate care that is safe, low barrier, youth‐centred, collaborative, flexible, evidence‐based, and trauma‐informed, and that integrates harm reduction and treatment for concurrent mental health disorders

Indigenous Peoples

Definition

- “Two-eyed seeing”

- The practice of creating wellness plans with the best evidence available from Western science and Indigenous Ways of Knowing.

Read about Etuaptmumk (Two-Eyed Seeing ) from the Manitoba Trauma Information and Education Centre

- Indigenous Peoples often understand the experience of physical pain as secondary to emotional pain. Emotional pain resulting from racism, colonization, premature death of kin, dispossession, dislocation, and community violence deeply impacts the health of Indigenous Peoples (Allan & Smylie, 2015).

- The biomedical system often lacks a holistic approach to the wellness of the individual beyond physical or psychological systems and fails to incorporate emotional, spiritual, community, and other contributors to well-being (Lavallee & Poole, 2010).

- Indigenous approaches value a holistic and communal approach that acknowledges the relationship with others and the land as healing elements (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.).

- A scoping review of cultural interventions for treating addictions in Indigenous populations found that culture-based treatment services included spiritual health, sweat lodges, and traditional teachings (Rowan et al., 2014).

- In Canada, it is recognized by the Truth and Reconciliation commission that Indigenous traditional culture is vital for client healing and wellness (Moran, 2020)

Read about an example of systemic racism and the negative impact of appropriate pain care.

Older Adults

Many older adults are living with co-occurring health conditions that need to be considered when taking opioid medications.

- Older adults with co-occurring psychiatric disorders and medical conditions are at a greater risk of developing a substance use disorder (SUD) or experiencing harmful interactions between prescription and non-prescription medications.

- Vision and memory problems can worsen with age, increasing the risk of overconsumption of prescribed medications, especially for clients with complex medical regimens.

- The risk of falls and fractures also increases among older adults who use opioids for pain-related conditions. Older adults should be informed to take more precautions when deciding on or undergoing opioid therapy.

(CCSA, 2018)

References

Addiction and Mental Health Collaborative Project Steering Committee. (2015). Collaboration for addiction and mental health care: Best advice. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Allan, B., & Smylie, J. (2015). First Peoples, second class treatment: The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Wellesley Institute.

Anishnawbe Health Toronto. (2011). Fasting. https://www.aht.ca/images/stories/TEACHINGS/Fasting.pdf

Bevers, K., Watts, L., Kishino, N. D., & Gatchel, R. J. (2016). The biopsychosocial model of the assessment, prevention, and treatment of chronic pain. US Neurology, 12(2), 98–104.

Bowen, J., Brindal, E., James-Martin, G., & Noakes, M. (2018). Randomized trial of a high protein, partial meal replacement program with or without alternate day fasting: similar effects on weight loss, retention status, nutritional, metabolic, and behavioral outcomes. Nutrients, 10(9), 1145.

Busse, J. W., Craigie, S., Juurlink, D. N., Buckley, D. N., Wang, L., Couban, R. J., Agoritsas, T., Akl, E. A., Carrasco-Labra, A., Cooper, L., Cull, C., da Costa, B. R., Frank, J. W., Grant, G., Iorio, A., Persaud, N., Stern, S., Tugwell, P., Vandvik, P. O., & Guyatt, G. H. (2017). Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ, 189(18), E659–E666.

Campbell, C. M., & Edwards, R. R. (2012). Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain Management, 2(3), 219–230.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2018). Improving quality of life: Substance use and aging. (2018). https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Substance-Use-and-Aging-Report-2018-en.pdf

Canadian Pain Task Force. (2019). Chronic pain in Canada: Laying a foundation for action. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2019/canadian-pain-task-force-June-2019-report-en.pdf

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2016). Making the choice, making it work: Treatment for opioid addiction. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/guides-and-publications/making-choice-en.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Module 5: Assessing and addressing opioid use disorder. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/training/oud/accessible/index.html

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). What is land-based treatment and healing? https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-What-is-Land-Based-Treatment-and-Healing.pdf

Foronda, C., Baptiste, D.‐L., Reinholdt, M. M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing,

27(3), 210–217.

Government of Canada. (2019). Talking to your healthcare provider about opioids. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/talking-with-healthcare-provider.html

Halwani, S. (2004). Racial inequality in access to health care services. Ontario Human Rights Commission. http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/race-policy-dialogue-papers/racial-inequality-access-health-care-services

Jeurgen, J. (2019). Signs of opiate abuse. (2019). Addiction Center. https://www.addictioncenter.com/opiates/symptoms-signs/

Lavallee, L. F., & Poole, J. M. (2010). Beyond recovery: Colonization, health and healing for Indigenous People in Canada. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8, 271–281. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1190&context=aprci

Leyland, A., Smylie, J., Cole, M., Kitty, D., Crowshoe, L., McKinney, V., Green, M., Funnell, S., Brascoupe, S., Dallaire, J., & Safarov, A. (2016). Health and health care implications of systemic racism on Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Indigenous Working Group of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada.

Lin, M. Y., & Kressin, N. R. (2015). Race/ethnicity and Americans’ experiences with treatment decision making. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(12), 1636–1642.

Linklater, R. (2014). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Fernwood Publishing.

Moran, R. (2020, October 5). Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved online from: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/truth-and-reconciliation-commission?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI2vj6-r2x6wIVCYnICh0RCwRVEAAYASAAEgLDbPD_BwE

Michalsen, A., Weidenhammer, W., Melchart, D., Langhorst, J., Saha, J. & Dobos, S. (2002). Short-term therapeutic fasting in the treatment of chronic pain and fatigue syndromes – wellbeing-being and side effects with and without mineral supplements. Research in Complementary and Natural Classical Medicine, 9(4), 221-227.

Michalsen, A. (2010). Prolonged fasting as a method of mood enhancement in chronic pain syndromes: A review of clinical evidence and mechanisms. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 14(2), 80–87.

Papaleontiou, M., Henderson, Jr, C. R., Turner, B. J., Moore, A. A., Olkhovskaya, Y., Amanfo, L., & Reid, M. C. (2010). Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(7), 1353–1369.

Peacock, S., & Patel, S. (2008). Cultural influences on pain. Reviews in Pain, 1(2), 6–9.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Government of Canada supports efforts to better understand how substance use affects Indigenous communities. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2019/07/government-of-canada-supports-efforts-to-better-understand-how-substance-use-affects-indigenous-communities.html

Rolita, L., Spegman, A., Tang, X., & Cronstein, B. N. (2013). Greater number of narcotic analgesic prescriptions for osteoarthritis is associated with falls and fractures in elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(3), 335–340.

Rowan, M., Poole, N., Shea, B., Gone, J. P., Mykota, D., Farag, M., Hopkins, C., Hall, L., Mushquash, C., & Dell, C. (2014). Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: Findings from a scoping study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 9, 34.

Wade, D.T., Halligan, P.W., 2017. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clinical Rehabilitation 31, 995–1004.