Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Identify and define the concept of bias.

- Explain the terms used to differentiate between forms of implicit bias.

- Describe the relationship between implicit bias, stigma, and harm.

- Reflect upon one’s own biases and explain how they relate to substance use.

- Explain individual and institutional strategies to mitigate bias.

Key Concepts

- Health and social service professionals’ stigmatizing attitudes towards people with substance use disorders negatively affect health care delivery and could result in treatment avoidance or interruption during relapse.

- Implicit bias incorporates several and interrelated concepts.

- Biased attitudes fuel unfair treatment towards people who use substances and undermine health-seeking behaviours.

What Is Implicit Bias?

Bias

“A bias is a tendency, an inclination, or a prejudice towards or against something or someone. Some biases are positive and helpful—like choosing to eat only foods that are considered healthy or staying away from someone who has knowingly caused harm. But biases are often based on stereotypes rather than actual knowledge of an individual or a circumstance.”

Implicit Bias

“Implicit bias refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect one’s understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner.”

Also referred to as unconscious bias, the attitudes or stereotypes associated with implicit bias contribute to stigma to those receiving services.

Implicit bias describes associations that alter our perceptions, informing our interactions and decision-making toward individuals based on the perceptions of a group of people (Marcelin et al., 2019). This type of bias can include both favourable and unfavourable assessments and is activated involuntarily, without a person’s awareness or intentional control. The implicit associations located within the subconscious cause feelings and attitudes towards other people based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, age, and appearance and behaviours such as substance use (Staats, Capatosto, Wright & Contractor, 2015).

Terms used in discussion of implicit bias include the following:

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Active bystander | A person who witnesses a situation, acknowledges the potential problem, and speaks up about it (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Bias | The tendency to favour one group over another; can be favourable or unfavourable and can be unconscious or conscious (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Cultural humility | Ongoing self-reflection: a lifelong commitment to continually evaluate one’s own behaviours, beliefs, and identities and determine how potential bias and assumptions may surface when collaborating with an individual from a different background (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Intent versus impact | A concept that the focus of behavioural change should consider the impact on the other regardless of the intent of the offending behaviour (i.e., whether the result of unconscious or conscious bias) (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Microaggression | Brief and commonplace daily verbal and nonverbal behavioural indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial, ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, and religious slights and insults; can occur when people are perceived as “other” (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Prejudice | Outward expressions of negative attitudes toward different social groups (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Stereotype | An oversimplified, fixed, and widely held belief about an entire group of people (Marcelin et al., 2019) |

| Discrimination | An action or a decision that treats a person or a group badly for reasons such as their race, age, or disability; these reasons, also called grounds, are protected under the Canadian Human Rights Act (Canadian Human Rights Commission, n.d.) |

How Implicit Bias Harms

KatarzynaBialasiewicz/iStock

Implicit biases modify the relationship between health and social service professionals and clients by decreasing the service users’ trust, self-efficacy, understanding, and satisfaction with services.

These changes affect clients’ ability to self-manage and adhere to treatment, and they limit the health and social service professional’s level of cultural proficiency, client centeredness, and even job satisfaction.

saiyood/iStock

People who feel more stigmatized are less likely to seek treatment, even if they have the same level of substance use disorder severity. They are more likely to drop out of treatment if they feel stigmatized and ashamed.

Research has shown that the more stigmatized the condition, as is the case with substance use disorders, the more likely the individual will self-stigmatize.

KatarzynaBialasiewicz/iStock

Countertransference occurs commonly among health and social service providers working with persons with substance use disorders. Countertransference occurs when providers project their feelings unconsciously onto the client. In these instances, health and social service providers may have their own personal or familial experience with substance abuse that creates difficulty in relating to the persons with substance use disorders.

Evidence of Bias in Healthcare

In studies examining implicit bias behaviours toward clients, this bias resulted in providers spending less time with and holding negative views towards clients, providing only the most basic of care or service and talking negatively about clients with other providers.

- In one study involving nurses, clients identified such behaviours as delaying care, failing to advocate for clients, being hurried or rough, and criticizing clients (Morgan, 2014).

- Howard and Chung (2000b) compared nurses’ attitudes with those of other groups of helping professionals (physicians, psychologists, social workers, clerical personnel, and chemical dependency personnel) and found that nurses were more negative and punitive, had more authoritarian orientations towards clients with substance use disorders than other groups, and supported compulsory treatment of clients with substance use disorders.

- Younger nurses and those with more education held more favorable attitudes towards clients with substance use disorders than those who were older or had fewer years of education (Howard & Chung, 2000a).

- Brener et al. (2010) found that clients being labelled or stigmatized can result in premature discharge and neglect and cause the client to feel frustrated, scared, depressed, angry, and upset, all of which can rupture the therapeutic relationship. The authors suggest that clients who use drugs are already sensitized to discrimination and may expect to be treated negatively by treatment staff.

Bias and Stigma

Bias and stigma are interrelated and reciprocal and can be hard to differentiate. Unfortunately, stigma is part of the today’s culture, which makes awareness critical.

The three main types of stigma related to substance use are social stigma, structural stigma, and self-stigma, as shown below.

| Social Stigma | Structural Stigma | Self-stigma |

|---|---|---|

| Negative attitudes towards people who use opioids and towards their friends and family members (also referred to as courtesy stigma) “They are just a junkie.” |

Social stigma from people who offer services to people who use drugs, including first responders, health and social service providers, government representatives “Here we go again.” |

Internalizing the negative social and structural messages around opioid use; over time, such messages become part of the individual’s self-image, impacting self-worth and esteem “I deserve what I get.” |

| Use of negative labels in conversation and in the media “Community residents fear for personal safety as methadone clinic moves into town.” |

Ignoring people affected by substance use or not taking their concerns or requests seriously “They’re just drug users.” |

Associated with delays in treatment seeking or avoidance of treatment “I’m not worth it.” |

| The use of negative images of people who use opioids | Not connecting with or delaying services for people—assigning them a lower priority | |

| Ignoring people who use opioids | Designing health and social services in ways that enhance stigma (long wait lists, services offered in less opportune hours, less staff) |

Adapted from Government of Canada, 2020

Stigma by Health Providers

Health and social service providers’ negative attitudes are known to lead to poor communication, resulting in a diminished therapeutic alliance and misattribution of physical illness symptoms to substance use problems, also referred to as diagnostic overshadowing.

For more information please see Module 4, Topic D.

- A scoping review of 28 studies found that health and social service providers regard for working with people with substance use disorders was consistently lower compared with other client groups, such as those experiencing depression or diabetes (van Boekel et al. 2013).

- The same authors found that attitudes of health and social service professionals towards people experiencing a substance use disorder were strongly negative; most of these professionals felt unable or unwilling to empathize with clients who use illicit drugs, resulting in these individuals receiving suboptimal care.

- Health and socials service workers report that people experiencing a substance use disorder are often perceived as their most difficult clients, as they expect them to be more dangerous, less cooperative, more aggressive, less truthful, less likely to complete treatment, and more demanding than other clients.

Impact of Bias

While unconscious bias describes associations or attitudes that unknowingly alter someone’s perceptions and therefore often go unrecognized by the individual; conscious bias is an explicit form of bias that is based on discriminatory beliefs and values and can be targeted in nature (Staats & Patton, 2013).

With both unconscious and conscious bias, health and social service providers’ ability to establish a trusting and compassionate therapeutic relationship with persons using opioids or persons with opioid disorder and their significant others can be markedly challenged.

- While neither form of bias belongs in the health and social service professions, conscious bias goes against the professional and ethical standards of health and social service providers, including pharmacists, social workers, and nurses, among others.

- Addressing unconscious bias involves willingness to alter one’s behaviour regardless of intent when the impact of one’s biases are uncovered or become evident (Teal et al., 2012). This is true in the context of substance use.

In a systemic review of 42 articles, FitzGerald and Hurst (2017) reported strong evidence of the prevalence among physicians and nurses of unconscious bias that affected clinical judgment and behaviour towards people who inject drugs.

How Is Implicit Bias Measured?

Health and social service providers may attest they treat all individuals equally and without prejudice. However, unconscious bias can be difficult to identify, and providers’ unconscious beliefs may differ from their explicit actions.

To measure unconscious bias, a questionnaire was developed by Banaji and Greenwald in 1998 called the Implicit Association Test (IAT).

- The IAT is an inexpensive and accessible tool that provides feedback on individual biases that is helpful for self-reflection (Marcelin et al., 2019).

- While the IAT does not test individual bias towards people with a substance abuse disorder, it does assess for factors that are associated with use and misuse, such as race, gender, disability, and skin tone.

How to Challenge Unconscious Bias

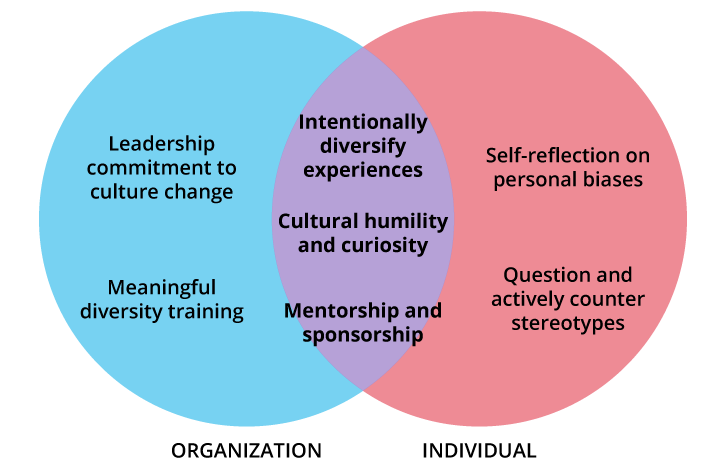

Unconscious bias is best addressed by a multi-pronged or multidimensional approach and most often incorporates the wider concepts of inclusion and equity reflected in the figure below.

Strategies to mitigate unconscious bias range from individual to community, institutional, and policy level, ensuring change is vertical or incorporated on multiple levels.

Strategies to Mitigate Unconscious Bias

Adapted from Marcelin, J. R., Siraj, D. S., Victor, R., Kotadia, S., & Maldonado, Y. A. (2019). The impact of unconscious bias in healthcare: How to recognize and mitigate it. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 220(Suppl. 2), S62–S73, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz214

These strategies are not standalone and work best when used or approached together and when they become part of a culture of care. Marcelin et al. (2019) suggested a combination of organizational, individual, and combined domains as the recommended approach to mitigate bias.

Organizational Strategies

To sustain individual change, organizations and institutions can provide leadership in how bias and negative stereotypes will not be supported (DiBrito et al., 2019).

- This direction can be achieved by intentionally recruiting into positions of decision-making and supporting individuals who are underrepresented.

- This leadership may also involve moving those with past lived experience with substances into advisory roles related to organizational processes and protocols focused on substance use and misuse admissions, programs, and treatment.

- Shifting the culture of an organization goes beyond establishing a mission statement or workshop for employees when the leadership commits to meaningful, informed, and ongoing change and evaluation (Smith, 2012).

Avenues to sustain change range from the formal, such as in-service training, to informal, such as regular discussions in team meetings.

Individual Strategies

Setting a regular time aside for self-reflection and the processing of events and interactions is one avenue for individuals working in substance treatment settings.

- Also referred to as deliberative reflection, this strategy encourages individuals to identify and evaluate how their own past experiences and identities influence their interactions with people who use or misuse substances.

- Taking the IAT is a step toward reflecting upon implicit bias. Outcomes can be discussed in a variety of work settings: supervisory meetings, mentorship arrangements, or professional development events such as grand rounds in a hospital.

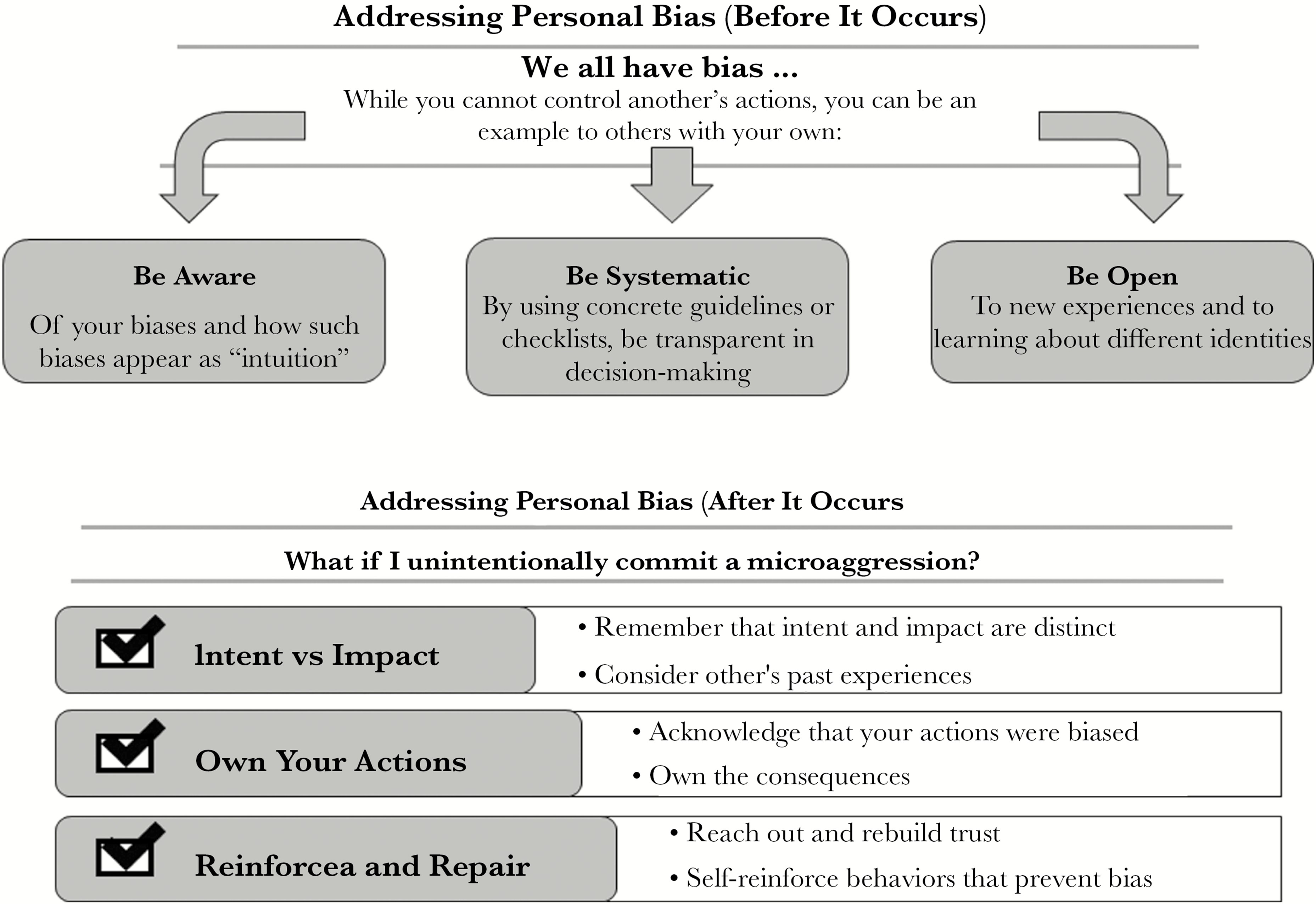

- Marcelin et al. (2019) provided a systematic way to decipher and work through biases before they occur, as well as after, shown in the figure below:

Strategies to Address Personal Bias Before and After It Occurs

Addressing personal bias before it occurs requires:

- Awareness – biases can appear as ‘intuition’

- Being systematic – concrete guidelines or checklists can help you be transparent with your decision-making.

- Being open – make an effort to learn about different identities and new experiences

Addressing personal bias after it occurs requires:

- Knowing the difference between intent and impact. Consider the other’s past experiences, their perspective and the potential impact of your actions.

- Owning your actions. Acknowledge your bias and own the consequences.

- Reinforcing and repairing what was damaged. Reach out and begin to rebuild trust with the other party. Prevent further bias by self-reinforcing corrective behaviours.

Marcelin, J. R., Siraj, D. S., Victor, R., Kotadia, S., & Maldonado, Y. (2019). The Impact of unconscious bias in healthcare: How to recognize and mitigate it. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 220(2), S62–S73. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz214

Strategies That Incorporate Both Organizational and Individual Efforts

Some strategies can help to identify and change bias for both the organization and the individual. Marcelin et al. (2019) suggest:

- Intentionally diversifying experiences by inviting laypeople or professionals with past substance use disorders to discuss their experiences interacting with health and social service providers.

- Exploring cultural humility, which can be broadened to include bias and stereotypes.

- Small group discussions or learning circles in which individual results to the IAT are discussed in safe and supportive ways can be helpful.

- Last, the authors suggested the concept of mentoring, which may again include laypeople or individuals who have coped with addiction in the past assuming leadership and mentoring positions.

In the following video, Anurag Gupta, founder and CEO of Be More America, defines explicit and implicit bias and what professionals can do to address it. He also offers practical suggestions on how to understand and reduce one’s own implicit biases.

Questions

Match the terms to the definition.

|

|

Outward expression of negative attitudes towards different social groups |

|

|

Ongoing self-reflection to evaluate one’s own behaviours, beliefs, and identities towards those who are different from oneself |

|

|

Oversimplified, fixed and widely held beliefs about an entire group of people |

|

|

A person who witnesses a situation, acknowledges the potential problem, and speaks up about it |

Correct! The following are the correct matches:

| Prejudice | Outward expression of negative attitudes towards different social groups |

| Cultural humility | Ongoing self-reflection to evaluate one’s own behaviours, beliefs, and identities towards those who are different from oneself |

| Stereotypes | Oversimplified, fixed and widely held beliefs about an entire group of people |

| Active bystander | A person who witnesses a situation, acknowledges the potential problem, and speaks up about it |

Incorrect. The following are the correct matches:

| Prejudice | Outward expression of negative attitudes towards different social groups |

| Cultural humility | Ongoing self-reflection to evaluate one’s own behaviours, beliefs, and identities towards those who are different from oneself |

| Stereotypes | Oversimplified, fixed and widely held beliefs about an entire group of people |

| Active bystander | A person who witnesses a situation, acknowledges the potential problem, and speaks up about it |

References

America Association of Family Physicians. (n.d.). The EveryONE Project: Implicit bias training. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/health_equity/implicit-bias-training-facilitator-guide.pdf

Burgess, D. J., Beach, M. C., & Saha, S. (2017). Mindfulness practice: A promising approach to reducing the effects of clinician implicit bias on patients. Patient Education and Counselling, 100(2), 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.09.005

Brener, L., Von Hippel, W., Von Hippel, C., Resnick, I., & Treloar, C. (2010). Perceptions of discriminatory treatment by staff as predictors of drug treatment completion: Utility of a mixed methods approach. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00173.x

Canadian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.). What is discrimination? https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/what-discrimination

DiBrito, S. R., Lopez, C. M., Jones, C., & Mather, A. (2019). Reducing implicit bias: Association of women surgeons #HeForShe task force best practice recommendations. Journal of American College of Surgeons, 228, 303–309.

Edgoose, J., Quiogue, M., & Sidhar, K. (2019). How to identify, understand, and unlearn implicit bias in patient care. Family Practice Management, 26(4), 29–33.

FitzGerald, C., & Hurst, S. (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review, BMC Medical Ethics, 18(19). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

Government of Canada. (2020). Stigma around substance use. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/stigma.html

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: IAT: An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

Luoma, J. B. (2010). Substance use stigma as a barrier to treatment and recovery. In R. A. Bankole (Eds.), Addiction medicine: Science and practice (pp. 1195–1216). Springer.

Marcelin, J. R., Siraj, D. S., Victor, R., Kotadia, S., & Maldonado, Y. (2019). The Impact of unconscious bias in healthcare: How to recognize and mitigate it. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 220(Suppl. 2), S62–S73. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz214

Morgan, B. D. (2014). Nursing attitudes toward patients with substance use disorders in pain. Pain Management Nursing, 15(1), 165–175.

Staats, C., & Patton, C. (2013). State of the science: implicit bias review: The Ohio State University Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University.

Staats, C. (2014). State of the science: implicit bias review 2014: The Ohio State University Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University.

Staas, C., Capatosto, K., Wright, R. & Contractor, D. (2015). State of the science: implicit bias review 2015: The Ohio State University Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University.

Smith, D. G. (2012). Building institutional capacity for diversity and inclusion in academic medicine. Academic Medicine, 87(11), 1511–1515.

Teal, C. R., Gill, A. C., Green, A. R., & Crandall, S. (2012). Helping medical learners recognize and manage bias toward certain patient groups. Medical Learners, 46, 80–88.

van Boekel, L., Brouwers, E., van Weeghel, J., & Garretsen, H. (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(1–2), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018