Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Differentiate between different kinds of peer support.

- Identify the different supports including those in the community as part of the recovery continuum.

- Explain an Indigenous framework of community support.

Key Concepts

- Community supports are an integral part of the continuum of care.

- Peer support is a key component of support in the community.

What Is a Continuum of Care?

The continuum of care includes a range of diverse and concurrent services that should be available to individuals experiencing or at risk for experiencing harms from opioid use. Visualized below is the range of service available. However, a person’s journey through the continuum of care is not necessarily meant to be linear.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

How Individuals Move Through the Continuum of Care

Some individuals might use all components of the continuum whereas others might not, and some might revisit different components as needed.

For example, those individuals who are experiencing more or chronic social determinants of health may need to be supported by additional services in the community, such as income and food security and shelter or transportation.

Community Support Imperatives

In order to be effective and accessible, community supports must:

- have low barriers to access,

- have flexible times (evening or weekends; not just traditional working hours),

- be culturally sensitive and knowledgeable,

- be geographically accessible, and

- be run by knowledgeable providers who are trustworthy and nonjudgmental.

As most individuals will require more than a single support in the community, it is helpful to engage a case manager or system navigator to advocate, coordinate, and arrange for seamless delivery of care.

NOTE: Peer support has also been shown to be highly effective in assisting people moving through the continuum of care (Cyr et al., 2016).

Peer Support in the Community

Tero Vesalainen/iStock

Peer support is defined as “the process of giving and receiving nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance from individuals with similar conditions or circumstances to achieve long-term recovery” (Trace & Wallace, 2016, p.143).

Peer support providers are people who have been successful in the recovery process and help others experiencing similar situations (SAMHSA, 2017). The role of a peer support worker complements but does not duplicate or replace the roles of therapists, case managers, and other members of a treatment team.

“Through shared understanding gained through actual experience, respect, and mutual empowerment, peer support workers help people become and stay engaged in the recovery process and reduce the likelihood of relapse”

Peer support services can effectively extend the reach of treatment beyond the clinical setting into the everyday environment of those seeking a successful, sustained recovery process. Peer support can take the form of:

- groups,

- individual counselling, and

- case management

Peer support has emerged as a highly effective and empowering method to manage the social context of health issues (Trace & Wallace, 2016). Peer support is particularly popular in the substance abuse and mental health fields.

Historically, peer support has been shown to be a key component of many existing addiction treatment and recovery approaches, such as:

- the community reinforcement approach,

- therapeutic communities, and

- 12-step programs.

Many terms have evolved as part of the peer support movement, some of which are shown below.

Definitions

- Peer support

- The process of giving and receiving nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance from individuals with similar conditions or circumstances to achieve long-term recovery from psychiatric, alcohol, and/or other drug-related problems

- Recovery

- A process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live self-directed lives, and strive to reach their full potential

- Peer support group

- Where people in recovery voluntarily gather together to receive support and provide support by sharing knowledge, experiences, and coping strategies, and offering understanding

- Peer provider (e.g., certified peer specialist, peer support specialist, mentor, and recovery coach)

- A person who uses his or her lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction, plus skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioral health settings to promote mind–body recovery and resiliency

- Peer mentorship

- Where individuals in later recovery provide nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance to individuals in earlier recovery with similar conditions or circumstances to achieve long-term recovery from psychiatric, alcohol, and/or other drug-related problems

Tracy, K., & Wallace, S. P. (2016). Benefits of peer support groups in the treatment of addiction. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 7, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S81535

Types of Peer Support

Within Canada, there is great diversity in what peer support looks like in the community for people using opioids and their significant others.

“The most common types are self-help support groups where peers meet regularly to provide mutual support, without the involvement of professionals, and one-to-one peer support such as co-counselling, mentoring or befriending”

Peer support services can also be specialized, with many being delivered by mainstream providers. Some examples of these specialized services are shown below.

Different Types of Peer Support

Support in housing, education, and employment

Social and recreational activities

Support in crisis (e.g., emergency rooms, acute wards and crisis houses)

Small businesses staffed by peers

Traditional healing, especially with Indigenous people

Paper and online information development and distribution

System navigation (e.g., case management)

Community education and anti-discrimination work

Material support (e.g., food, clothing, storage, Internet, transportation)

Systemic and individual advocacy

Artistic and cultural activities

Recovery education for peers

Mentoring and counselling

(Cyr, McKee, O’Hagan & Priest, 2016)

Nadiinko/iStock (housing); palau83/iStock (recreation); Jo/iStock (hospital); phototechno/iStock (business); GreenTana/iStock (Indigenous); da-vooda/iStock (information); Vladislav Popov/iStock (navigation); ponsuwan/iStock (community); etonie/iStock (food); Blankstock/iStock (advocacy, recovery education, mentoring); matsabe/iStock (artistic)

Principles of Core Competencies

“Core competencies for peer workers reflect certain foundational principles identified by members of the mental health consumer and substance use disorder recovery communities”

Definitions

- Recovery-oriented

- Peer workers hold out hope to those they serve, partnering with them to envision and achieve a meaningful and purposeful life. Peer workers help those they serve identify and build on strengths and empower them to choose for themselves, recognizing that there are multiple pathways to recovery.

- Person-centred

- Peer recovery support services are always directed by the person participating in services. Peer recovery support is personalized to align with the specific hopes, goals, and preferences of the people served and to respond to specific needs the people have identified to the peer worker.

- Voluntary

- Peer workers are partners or consultants to those they serve. They do not dictate the types of services provided or the elements of recovery plans that will guide their work with peers. Participation in peer recovery support services is always contingent on peer choice.

- Relationship-focused

- The relationship between the peer worker and the peer is the foundation on which peer recovery support services and support are provided. The relationship between the peer worker and peer is respectful, trusting, empathetic, collaborative, and mutual.

- Trauma-informed

- Peer recovery support uses a strength-based framework that emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety and creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment.

Relationship Between the Individual and the Community

A community-based approach that encompasses the spectrum of care of prevention, treatment, and aftercare programs for the individual should be mindful of culture.

Cultural relevance in the community can vary from adding an Indigenous component to the disease model of Alcoholics Anonymous to developing community-based participatory programs with a sociocultural-spiritual model (Mohatt et al., 2004; Robinson et al., 2006).

Services that emphasize the importance of culture and community in the spectrum of care mean that these services take place in the person’s home community. This allows for important connections to be fostered while the individual is in treatment and supports a positive transition back home should the individual be in residential care.

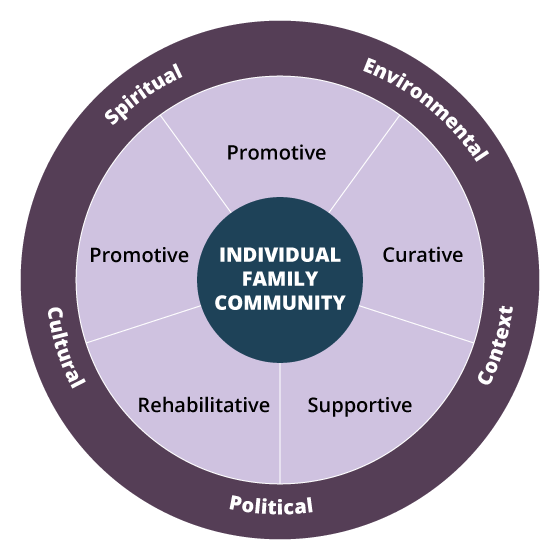

The image below highlights the Indigenous framework that honours the interrelatedness relationship between the individual and the community. This relationship must be supported by distal factors of the environment, political systems, cultural discourse, and the spiritual realm.

Primary Health Care Model

Adopted by Nisnawbe Aski Nation and the Sioux Lookout First Nations health authority.

Three layered circle. The centre circle reads Individual Family Community. The middle circle is divided into 4 sections: Promotive, Curative, Supportive, Rehabilitative, and Preventative. The outer circle has five terms around it. Environmental appears over the Promotive and Curative sections, Context appears over Curative and Supportive, Political appears over Supportive and Rehabilitative, Cultural appears over Rehabilitative and Preventative, and Spiritual appears over Preventative and Promotive.

Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority. (2006). The Sioux Lookout Anishnabe District health plan: Building a plan to improve our health. https://www.nodin.on.ca/dhp.htm

KEY TAKEAWAY: Community supports are unique to each community. It is the role of the practitioner to know what resources exist to support the client. Overarching national or provincial and territorial resources should be consulted as one step toward understanding the role of resources.

Activity: The document provided here is an activity you can complete on your own or with a peer or mentor. It presents a case for you to consider. Discuss any gaps in services.

Questions

Match the terms to the definitions.

|

|

a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness |

|

|

a person who uses his or her lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction, plus skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioural health settings to promote mind–body recovery and resiliency |

|

|

giving and receiving nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance from individuals with similar conditions |

|

|

individuals in later recovery provide nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance to individuals with similar conditions in earlier recovery |

Correct! The following matches are correct:

| recovery | a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness |

| peer provider | a person who uses his or her lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction, plus skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioural health settings to promote mind–body recovery and resiliency |

| peer support | giving and receiving nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance from individuals with similar conditions |

| peer mentorship | individuals in later recovery provide nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance to individuals with similar conditions in earlier recovery |

Incorrect. The following matches are correct:

| recovery | a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness |

| peer provider | a person who uses his or her lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction, plus skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioural health settings to promote mind–body recovery and resiliency |

| peer support | giving and receiving nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance from individuals with similar conditions |

| peer mentorship | individuals in later recovery provide nonprofessional, nonclinical assistance to individuals with similar conditions in earlier recovery |

References

BC First Responders’ Mental Health. (2017). Supporting mental health in first responders: Overview of peer support programs. https://bcfirstrespondersmentalhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Overview-of-Peer-Support-Progams-170619.pdf

Coatsworth-Puspoky, R., Forchuk, C., & Ward-Griffin, C. (2006). Peer support relationships: An unexplored interpersonal process in mental health. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(5), 490–497.

Cyr, C., McKee, H., O’Hagan, M., & Priest, R. (2016) Making the case for peer support: Report to the Peer Support Project Committee of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (2nd ed.). Mental Health Commission of Canada. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2016-07/MHCC_Making_the_Case_for_Peer_Support_2016_Eng.pdf

Davidson, L., Chinman, M., Kloos, B., Weingarten, R., Stayner, D., & Tebes, J. K. (1999). Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6(2), 165–187.

Dumont, J., & Jones, K. (2002). Findings from a consumer/survivor defined alternative to psychiatric hospitalization. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute. Outlook, 3(Spring), 4–6.

McAuliffe, W. E. (2012) A randomized controlled trial of recovery training and self-help for opioid addicts in New England and Hong Kong, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 22(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1990.10472544

MacPherson, D. (2001, April 4). Framework for action: A four-pillar approach to drug problems in Vancouver. City of Vancouver. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/596f8b1ca803bb496e345ac8/t/59c97123f5e231aeec5a781d/1506373924623/A_Four-Pillar_Approach_to_Drug_Problems_in_Vancouv.pdf

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (n.d.). Peer support. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/what-we-do/recovery/peer-support

Mohatt, G. V., Hazel, K. L., Allen, J., Stachelrodt, M., Hensel, C., & Fath, R. (2004). Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(3–4), 263–273.

Ochocka, J., Nelson, G., Janzen, R., & Trainor, J. (2006). A longitudinal study of mental health consumer/survivor initiatives: Part 3—A qualitative study of impacts of participation on new members. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(3), 273–283.

Penn, R., & Strike, C. (2012). Connecting in the community: Outreach programs for people who use drugs. http://www.catie.ca/en/pif/spring-2012/connecting-community-outreachprograms-people-who-use-drugs

Ratzlaff, S., McDiarmid, D., Marty, D., & Rapp, C. (2006). The Kansas consumer as provider program: Measuring the effects of a supported education initiative. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(3), 174–182.

Resnick, S. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2008). Integrating peer-provided services: A quasi-experimental study of recovery orientation, confidence, and empowerment. Psychiatric Services, 59(11), 1307–-1317.

Robinson, G., Warren, H., Samu, K., Wheeler, A., Matangi-Karsten, H., & Agnew F. (2006). Pacific healthcare workers and their treatment interventions for Pacific clients with alcohol and drug issues in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal, 119(1228), U1809.

Salzer, M. S. (2002). Consumer-delivered services as best practice in mental health care delivery and the development of practice guidelines. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills, 6(3), 355-382.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). SAMHSA core competencies for peer workers. https://www.samhsa.gov/brss-tacs/recovery-support-tools/peers/core-competencies-peer-workers

Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority. (2006). The Sioux Lookout Anishinaabe District health plan: Building a plan to improve our health. https://www.nodin.on.ca/dhp.htm

Tracy, K., & Wallace, S. P. (2016). Benefits of peer support groups in the treatment of addiction. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 7, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S8153

Waterloo Region Integrated Drugs Strategy Special Committee on Opioid Response. (2018). Waterloo region opioid response plan.