Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Discuss the importance of considering the role of culture in pain management.

- Describe specific needs of culturally appropriate pain management care within sub-populations.

- Recognize differences between Western biomedicine and other healing practices.

- Describe Indigenous healing in the current Canadian health care system.

Key Concepts

- Cultural factors influence beliefs that affect the management of illness in multiple ways, including decision-making control in health care settings, health-seeking behaviours, definitions of symptoms of normal and abnormal, and understanding about what causes illness.

- The biomedical model has shifted to a biopsychosocial model of pain that encompasses biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors unique to individuals, as well as their experience of pain.

- Various populations require specific approaches to pain management (e.g., youth and adolescents, Indigenous Peoples, and older adults).

- Complex disorders require a comprehensive approach to pain management that takes the whole person into account, including the cultural dimension.

- A holistic approach to pain is promoted in other cultural healing practices, such as

- Ayurveda (traditional Indian medicine)

- traditional Chinese medicine

- Indigenous healing practices

- Indigenous-directed health and community services are being provided in Canada.

Cultural Considerations in Pain Management

Approximately 20 percent of the population experiences chronic pain. The high rate of opioid use in the Canadian population reflects an urgent need to improve the management of chronic pain (Schopflocher, Taenzer & Jovey, 2011).

“An individual’s culture influences how pain is perceived, experienced, and communicated.”

Culture is understood to be a socially constructed “lens” through which individuals see their world and their reality (Peacock & Patel, 2008). Thus, cultural factors influence individuals’:

- beliefs,

- perceptions, and

- interpretations of symptoms, including

- whether they consider them to be normal or abnormal,

- what they believe may have caused them, and

- what help they should seek out.

Cross-cultural perceptions of pain and pain management vary (e.g., sweat lodges, acupuncture, ceremonial practices), and non-traditional cultural practices should be considered when managing pain or pain-related symptoms.

- Pain perception may differ among ethnic groups, although evidence for this is still scarce. Individuals should always be consulted on their pain perception regardless of their ethnicity (Campbell & Edwards, 2012).

Cultural factors intersect with socio-demographic factors in influencing how a person perceives and responds to pain. Populations in lower socioeconomic groups may experience poorer health and higher pain (Dorner et. Al., 2011).

Biopsychosocial Model of Pain

Cultural factors also intersect with biological and psychological factors. There has been a shift from the traditional biomedical model of pain to a biopsychosocial model that encompasses the whole person and their experience of pain.

Unique biological, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual factors can impact the nervous system and affect how people develop and experience pain. Both the assessment of pain and the treatment of pain are guided by the biopsychosocial model and target:

- sociocultural determinants of pain,

- perceptions of injustice,

- social exclusion,

- stigmatization,

- pain catastrophizing,

- depressed mood,

- motivations,

- anxiety levels, and

- biological factors (Wijma, van Wilgen, Meeus, & Nijs, 2016).

Provided below is a list of sample questions to ask related to individual perceptions and experiences with pain. Consider cultural and socio-demographic factors in your conversations about pain.

Culturally Appropriate Care in Managing Pain in Specific Populations

Various populations require specific approaches to the treatment and management of pain.

Adolescents and Youth

Adolescents and youth require developmentally and culturally appropriate care that is:

- safe,

- low barrier,

- youth-centred,

- collaborative,

- flexible,

- evidence based, and

- trauma informed.

Families (as defined by the individual) should be involved as appropriate. Interventions should be tailored to the unique needs of youth and not presume a “one‐size-fits-all” approach.

Indigenous Peoples

Definition

- Two-eyed seeing

- The practice of creating wellness plans with the best evidence available from Western science and Indigenous Ways of Knowing.

Wellness plans should incorporate “two‐eyed seeing”. Indigenous Peoples often describe the experience of physical pain as secondary to emotional pain. Emotional pain deeply impacts the health of Indigenous Peoples (Allan & Smylie, 2015), and is often resulting from:

- racism,

- colonization,

- premature death of kin,

- dispossession,

- dislocation, and

- community violence.

Urban Indigenous Peoples may also experience a disconnection to community and land, and a loss of the sense of self and of ceremony. The therapeutic relationship should look at maintaining connection and ceremony despite dislocation as part of the treatment.

Traditional healers approach the person as an integrated whole. Health is restored by restoring balance among mind, body, spirit, and community.

Older Adults

Many older adults are living with co-occurring health conditions that result in chronic pain.

- Older adults with co-occurring psychiatric disorders and medical conditions are at a greater risk of developing a substance use disorder (SUD) or experiencing harmful interactions between prescription and non-prescription medications.

- Vision and memory problems can worsen with age, increasing the risk of overconsumption of prescribed medications, especially for clients with complex medical regimens.

- The risk of falls and fractures also increases among older adults who are treated with opioids for pain-related conditions because of the effects of opioids on the central nervous system. Older adults should be informed to take greater precautions when deciding on or undergoing opioid therapy.

(CCSA, 2018)

Case Study: Robert

Robert retired at age 65, selling the hardware store he had owned with his wife, Jean, for 36 years.

monkeybusinessimages/iStock

– Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2018, p 65

Western Biomedicine and Complementary Cultural Healing Practices

Western biomedicine has seen great advances in chemistry, pharmacology, surgery, molecular biology, and laboratory techniques. There have been great achievements in Western medicine, such as:

- increasing life expectancy,

- reducing infant mortality, and

- reducing the spread of infectious diseases

However, many chronic and degenerative conditions are not adequately addressed with Western medicine and are associated with chronic pain.

Multifactorial and complex disorders require a comprehensive approach that takes the whole individual into account. The concept of treating the whole individual is an integral part of a number of non-western therapeutic practices, including

- Ayurveda (traditional Indian medicine)

- traditional Chinese medicine

- Indigenous healing practices

- In 2009, a meta-analysis that included 21 studies (2949 cases in total) compared traditional Chinese herbal medicine with alpha2-adrenergic or opioid agonists and found that Chinese herbal medicine was better at improving withdrawal symptoms (Liu et al. 2009).

Indigenous traditional healing practices “emphasize communication with spirit beings and direct requests for healing through prayer, song, and ceremony”. Traditional healers look for “areas of disharmony and imbalance” within the external community, the community of client’s mind, and in the relationship of bodies, the earth, plants, animals, and all of creation (Mehl-Madrona, 2019).

- Healing is sought through balance and harmony in the person’s relationships.

- Traditional foods are seen as an important medicine for health promotion and community development.

- Indigenous Peoples treat addictions through cultural interventions that include a spiritual component. From sweat lodges to art creation, regionally diverse interventions depend on the context of the specific Indigenous treatment program.

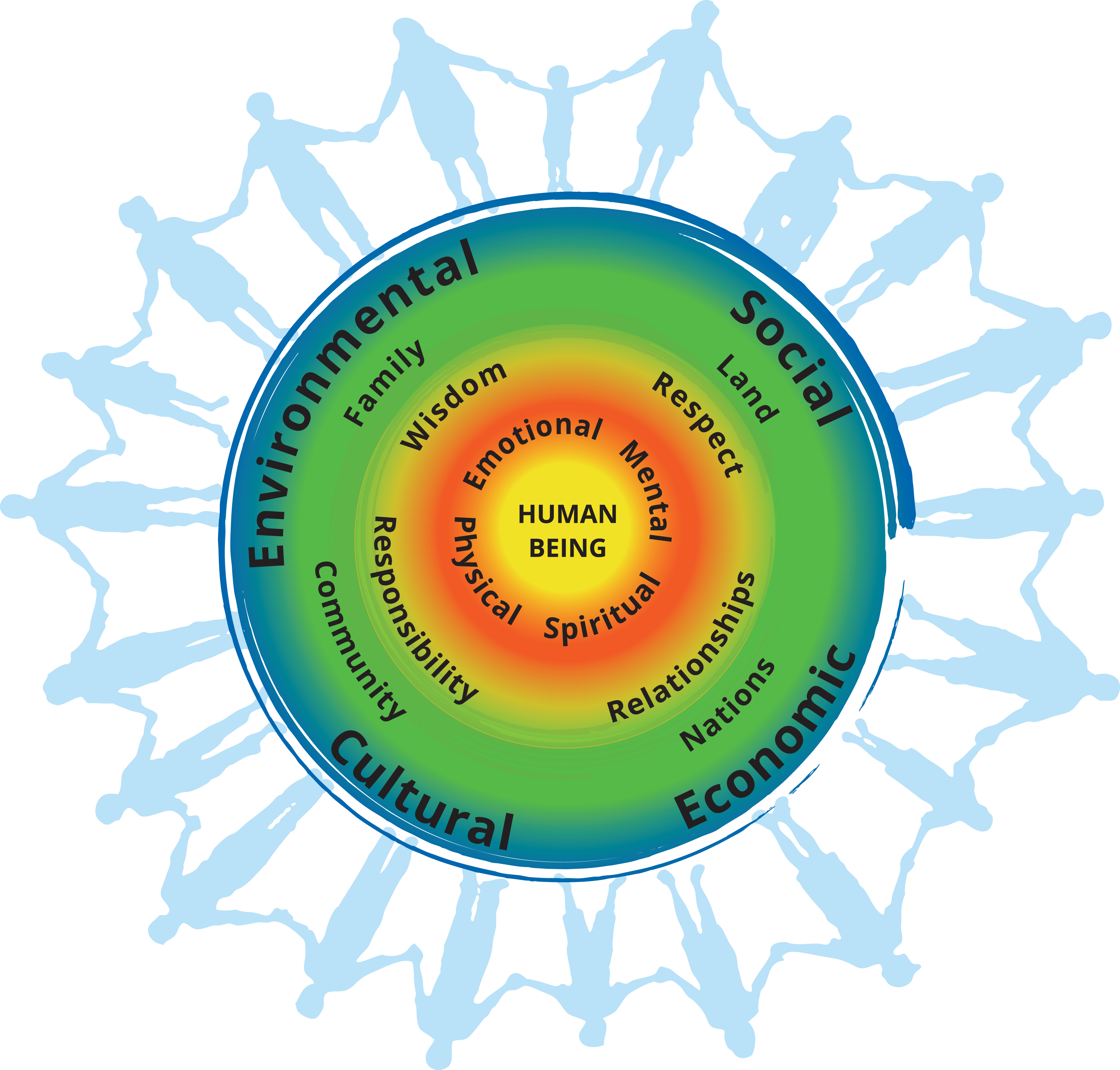

This image, developed by B.C.’s First Nations Health Authority, represents a fluid and holistic concept of health and wellness. The center circle represents the individual human being. The second circle illustrates the importance of the mental, emotional, spiritual and physical facets of a healthy and balanced life. The third circle represents the overarching values that support wellness: respect, wisdom, responsibility and relationships. The fourth circle depicts the people and places around each human being. And the outer circle depicts the social, cultural, economic and environmental determinants of health and well-being. This image is intended as a starting point for individuals and communities to adapt to create their own models” (Mehl-Madrona, 2019). | FNHA First Nations Perspective on Health and Wellness Poster

FNHA. (n.d.). First Nations Perspective on Health and Wellness [Image]. First Nations Health Authority. https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-and-the-first-nations-health-authority/first-nations-perspective-on-wellness

The Role of Indigenous Healing Practices in The Current Health Care System

Colonization has had a longstanding impact on Indigenous Peoples. They “face more poverty, violence, stigma and discrimination, substance use, sexually transmitted infections, and barriers to accessing health care services than other groups in the population” (Mehl-Madrona, 2019).

The social determinants of health contribute significantly to perpetuating health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Numerous determinants of health have an impact on First Nations health and wellness.

For example:

Intergenerational trauma from Residential Schools

Many adults and older adults in Indigenous communities attended residential schools. The rates of suicidal ideations among First Nations youth are higher when one or more parents and/or grandparents attended an Indian residential school.

Income disparities and unemployment

The median income among Indigenous peoples is 30 percent lower than among other Canadians and unemployment rates are more than double the rate for other Canadians.

Housing

First Nations experience four times the rate of overcrowding in homes and four times the rate of need for major home repair.

GreenTana/iStock (residential school); Nadiinko/iStock (housing); justinroque/iStock (income disparity)

Traditional Indigenous healing practices address the whole person and are important in the treatment and management of pain and opioid use. Promising and emerging responses to respect and incorporate Indigenous culture and healing practices in health and social services include the following (Allan & Smylie, 2015):

- Indigenous directed health and health-related services

- Efforts to increase the number of Indigenous health and social service providers

- The creation of roles such as Indigenous client navigators to serve as a bridge between Indigenous clients and the health and social service system

- Cultural safety training of health and social service providers to address the negative impact of power relations on health outcomes

- Trauma-informed care, which addresses the impact of historic, collective, and intergenerational trauma

- Interventions addressing racism among health and social service providers

Examples of health services programs directed by Indigenous peoples include the following (Allan & Smylie, 2015):

- First Nations communities administering and managing health and social service centres

- Urban Indigenous health centres, the majority of which are run by Indigenous boards of directors and offer both traditional healing and medical services

Community-directed Indigenous services related to social determinants of health (e.g., housing, education, employment, language, and culture) are growing in number. There is also more Indigenous representation in community-based and health-impacting services and programs. Some mainstream community health centres, such as the Queen West Community Health Centre in Toronto, offer Indigenous-specific programming.

The Thunderbird Partnership Foundation published the Native Wellness Assessment (NWA-O). Completed assessments can be submitted online to receive a client report which provides an analysis and interpretation of the individual’s results.

Questions

References

Allan, B., & Smylie, J. (2015). First Peoples, second class treatment: The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada [Discussion paper]. Wellesley Institute.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2018). Improving quality of life: Substance use and aging. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Substance-Use-and-Aging-Report-2018-en.pdf

Canadian Pain Task Force. (2019). Chronic pain in Canada: Laying a foundation for action. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2019.html#a1.3

Canadian Psychological Association. (2019). Recommendations for addressing the opioid crisis in Canada. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Task_Forces/OpioidTaskforceReport_June2019.pdf

Campbell, C. M., & Edwards, R. R. (2012). Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain management, 2(3), 219-230.

Emerson, B., Haden, M., Kendall, P., Mathias, R., & Robert Parker, R. (2005). A public health approach to drug control in Canada. Health Officers Council of British Columbia.

Darnall, B. D., Carr, D. B., & Schatman, M. E. (2017). Pain psychology and the biopsychosocial model of pain treatment: Ethical imperatives and social responsibility. Pain Medicine, 18(8), 1413–1415.

Doosti, F., Dashti, S., Tabatabai, S. M., & Hosseinzadeh, H. (2013). Traditional Chinese and Indian medicine in the treatment of opioid-dependence: A review. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine, 3(3), 205.

Dorner, T. E., Muckenhuber, J., Stronegger, W. J., Ràsky, É., Gustorff, B., & Freidl, W. (2011). The impact of socio-economic status on pain and the perception of disability due to pain. European journal of pain, 15(1), 103-109.

Gatchel, R. J., Peng, Y. B., Peters, M. L., Fuchs, P. N., & Turk, D. C. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 581.

Givler, A., & Maani-Fogelman, P. (2019). The importance of cultural competence in pain and palliative care. StatPearls Publishing.

Green, C. R., Anderson, K. O., Baker, T. A., Campbell, L. C., Decker, S., Fillingim, R. B., Kalauokalani, D. A., Lasch, K. E., Myers, C., Tait, R. C., Todd, K. H., & Vallerand, A. H. (2003). The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Medicine, 4(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x

Hall, W. J., Chapman, M. V., Lee, K. M., Merino, Y. M., Thomas, T. W., Payne, B. K., Eng, E., Day, S. H., & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60-e76. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

Health Canada. (2015). First Nations mental wellness continuum framework. https://www.thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/24-14-1273-FN-Mental-Wellness-Framework-EN05_low.pdf

Helman, C. (2007). Culture, health and illness. CRC Press.

Liu, T. T., Shi, J., Epstein, D. H., Bao, Y. P., & Lu, L. (2009). A meta-analysis of Chinese herbal medicine in treatment of managed withdrawal from heroin. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 29(1), 17–25.

Mehl-Madrona, L. (2019). What can Western medicine learn from Indigenous healing traditions? The Positive Side. CATIE (Community AIDS Treatment Information Exchange). https://www.catie.ca/en/positiveside/spring-2019/indigenous-healing

Papaleontiou, M., Henderson, Jr, C. R., Turner, B. J., Moore, A. A., Olkhovskaya, Y., Amanfo, L., & Reid, M. C. (2010). Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(7), 1353–1369.

Peacock, S., & Patel, S. (2008). Cultural influences on pain. Reviews in Pain, 1(2), 6–9.

Penner, L. A., Blair, I. V., Albrecht, T. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2014). Reducing racial health care disparities: a social psychological analysis. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 204–212.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019). Government of Canada supports efforts to better understand how substance use affects Indigenous communities. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2019/07/government-of-canada-supports-efforts-to-better-understand-how-substance-use-affects-indigenous-communities.html

Rolita, L., Spegman, A., Tang, X., & Cronstein, B. N. (2013). Greater number of narcotic analgesic prescriptions for osteoarthritis is associated with falls and fractures in elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(3), 335–340.

Rowan, M., Poole, N., Shea, B., Gone, J. P., Mykota, D., Farag, M., Hopkins, C., Hall, L., Mushquash, C., & Dell, C. (2014). Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: Findings from a scoping study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 9(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-9-34

Schopflocher, D., Taenzer, P., & Jovey, R. (2011). The prevalence of chronic pain in Canada. Pain Research and Management, 16(6), 445–450.

Wang, S. C. (2013). Western biomedicine and eastern therapeutics: An integrative strategy for personalized and preventive healthcare. World Scientific.

Wijma, A. J., van Wilgen, C. P., Meeus, M., & Nijs, J. (2016). Clinical biopsychosocial physiotherapy assessment of patients with chronic pain: The first step in pain neuroscience education. Physiotherapy theory and practice, 32(5), 368-384.