Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Describe harm reduction services available in Canada to persons using opioids and those with opioid use disorder

- Describe the purpose of supervised consumption sites and how they work

- Explain the goals and outcomes of needle exchange programs

Key Concepts

- Supervised consumption sites provide a safe space, supports, supplies, and resources to persons who use drugs

- Needle exchange and distribution programs provide sterile needles and associated equipment, education, and resources to people who use injection drugs to prevent needle re-use and sharing, and the transmission of infectious disease, including HIV and hepatitis C

- Naloxone kits can be used to reverse opioid-induced respiratory depression

Supervised Consumption Sites

A supervised consumption site is a health service that provides sterile injection supplies, a facility to inject pre-obtained, typically unregulated substances, and personnel trained to assist and/or treat health outcomes such as an overdose. Additional services may include:

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

- Supervised consumption of non-injection drugs, including via inhalation

- Provision of peer-assisted substance administration

- Provision of drug checking technologies

- Naloxone distribution

- Referral to other supports including drug treatment programs

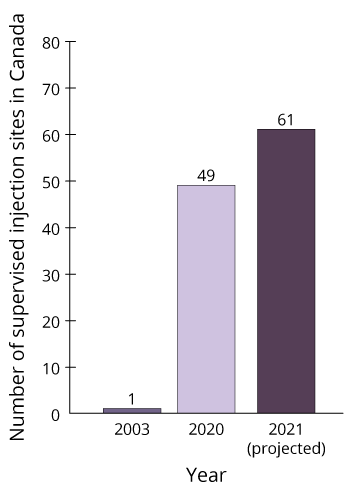

Canada’s first supervised injection site, InSite, was established in Vancouver in 2003. As opioid overdoses and deaths began to increase in the mid 2010s, there were calls for additional supervised injection/consumption facilities to be established.

- As of January 2020, 49 sites are currently operating in Canada, with 12 additional sites at various stages of the review process.

The term “overdose prevention site” is often used to describe temporary services, which may be sanctioned (i.e., approved) or unsanctioned by regional or municipal governments.

- As of January 2020, there have been zero overdose fatalities at Canadian supervised injection sites.

- Most research in Canada on supervised consumption sites targets the site’s primary harm reduction mandate; evidence on outcomes beyond this mandate such as referral to treatment is mixed.

- To date, there is no evidence that supervised consumption sites increase drug-related crime, but research is limited.

Needle Exchange Programs (NEPS)/Distribution

Needle exchange and distribution programs are designed to provide clean needles to persons who use drugs with the primary goal of preventing the sharing of needles and the subsequent risk of Hepatitis C and HIV transmission.

Inna Luzan/iStock

- Needle exchange programs also exchange used needles, which are then disposed of safely.

- NEPs are recognized as one of the most cost-effective public health interventions (Wilson et. al., 2015).

- Many needle exchange/distribution programs also offer free HIV testing, counseling and support, and referrals to health and social service agencies.

- Best Practice Recommendations identify the importance for NEPs to find a balance between providing direct primary care services and helping their clients access services elsewhere in the community (BC Harm Reduction Strategies and Services (BCHRSS) Committee, 2008).

Evidence of the Effectiveness of NEPs

In Canada, a study found that after the closure of needle-exchange clinics in Victoria, the prevalence of needle sharing was significantly higher (23%) compared with Vancouver (8%) where the needle exchange clinics remained open (Ivsins et. al, 2010)

Meta-analyses and research measuring the efficacy of needle exchange and distribution programs have typically failed to detect an increase in positive status in HIV or hepatitis C transmission rates (Mir et. al, 2018), however:

- These programs are often designed to work with individuals who are already at higher risk of infection prior to participation in a program

- It is difficult to isolate the impact of needle programs from other harm reduction and treatment interventions

- Methodological challenges and low-quality data make it difficult to draw conclusions

- There may be variability in efficacy between specific programs and specific jurisdictions

Best practice recommendations for NEPs include:

- offering a variety of needle and syringe types (i.e., gauge, size and brand)

- educating clients about proper use and disposal;

- providing pre-packaged safer injection kits (needles/syringes, cookers, filters, ascorbic acid when required, sterile water for injection, alcohol swabs, tourniquets, condom and lubricant) (Working Group on Best Practices for Harm Reduction Programs in Canada, 2013)

The benefits of needle exchange and distribution programs include:

- Provision of evidenced-based harm reduction resources, appropriate equipment and education on safe injection procedures to people who use drugs

- A significant decline in equipment sharing and re-using practices among clients

- Health resources, materials, and education available at Needle Syringe Programs

- Safer drug and safe sexual practices recommended to clients

For more information on the Indigenous harm reduction point of view, see Topic 4E.

Naloxone Kits

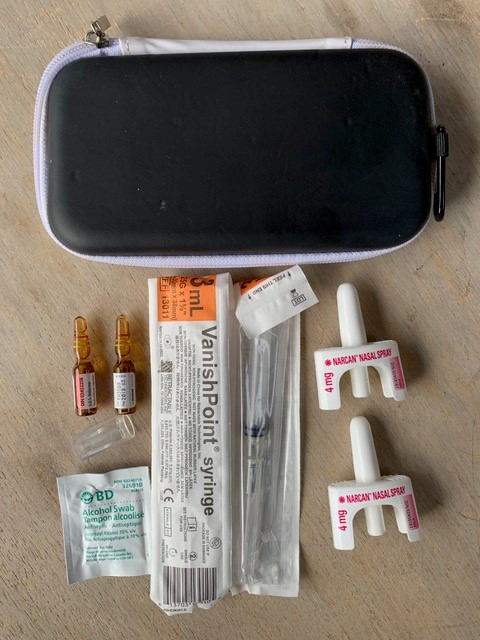

© Michael Beazely

Naloxone kits typically include:

- A hard case

- Two or more doses of naloxone

- Narcan® Nasal Spray (4 mg naloxone /0.1 mL) OR

- 1 mL ampoules or vials of naloxone hydrochloride 0.4 mg/mL intramuscular injection

- Rescue breathing barrier

- Pair of non-latex gloves

- Training card and/or instructional insert

- Alcohol swaps (for injectable naloxone)

- Two safety syringes, 25g, 1-inch needle (for injectable naloxone)

- Ampoule opening device (for injectable naloxone)

Depending on the jurisdiction, naloxone kits can be obtained (free of charge, often without a health card) from pharmacies, public health units, overdose prevention sites, and other outreach services.

For more information about naloxone kits, see Module 8, Topic E.

Effective Harm Reduction Programs

According to Strike et al. (2013) characteristics of the most effective harm reduction programs are those that

- Are implemented rapidly in response to a community need

- Provide a comprehensive range of well-coordinated and flexible services

- Involve the community in planning and implementation

- Continually assess and understand local community needs

- Make services available in multiple locations with varied hours of operation

- Provide community-based outreach to people who use drugs where they live and use or buy drugs

- Communicate respect for persons who use drugs and their families to ensure all are treated with dignity and with sensitivity to cultural, racial, ethnic and gender-based characteristics

- Provide easily accessible sterile injection equipment to reduce the re-use of injection equipment

- Educate those using injection drugs regarding risk and services for risk reduction

- Are sustainable

- Provide a supportive political environment, i.e. are supported by municipal, regional, provincial, and federal governments

- Target persons who use drugs and are living with HIV as well as their sexual partners

Needle exchange programs and opioid substitution therapy are types of harm reduction programs that may be coupled with other therapies to support people who inject drugs (PWID).

- Combined harm reduction approaches are likely to be more effective and cost-effective (Craig, 2014)

In addition to opioid maintenance therapy, a continuum of care should offer other services to meet the needs of various stages of opioid reduction such as:

- tapering,

- detox-based approaches, and finally

- abstinence-based approaches.

Stop and Think

Now that you have reviewed this content, consider the following scenarios:

What harm reduction services are available in your community?

Where can you get a naloxone kit?

Where are they located?

What are the hours?

By becoming familiar with your local services, you are better equipped to apply harm reduction strategies as needed.

References

BC Harm Reduction Strategies and Services Committee. (2008). Best practices for British Columbia’s harm reduction supply distribution program. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Guidelines%20and%20Manuals/Epid/Other/BestPractices.pdf

Cornish, R., Macleod, J., Strang, J., Vickerman, P., & Hickman, M. (2010). Risk of death during and after opiate substitution treatment in primary care: prospective observational study in UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ, 341, c5475.

Craig, A. P., Thein, H. H., Zhang, L., Gray, R. T., Henderson, K., Wilson, D., Gorgens, M., & Wilson, D. P. (2014). Spending of HIV resources in Asia and Eastern Europe: Systematic review reveals the need to shift funding allocations towards priority populations. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 18822.

Ivsins, A., Chow, C., Marsh, D., Macdonald, S., Stockwell, T., & Vallance, K. (2010). Drug use trends in Victoria and Vancouver, and changes in injection drug use after the closure of Victoria’s fixed site needle exchange. Centre for Addictions Research of BC.

Kennedy, M. C., Karamouzian, M., & Kerr, T. (2017). Public health and public order outcomes associated with supervised drug consumption facilities: A systematic Review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 14, 161–183.

Mir, M. U., Akhtar, F., Zhang, M., Thomas, N. J., & Shao, H. (2018). A meta-analysis of the association between needle exchange programs and HIV seroconversion among injection drug users. Cureus, 10(9), e3328.

Platt, L., Minozzi, S., Reed, J., Vickerman, P., Hagan, H., French, C., Jordan, A., Degenhardt, L., Hope, V., Hutchinson, S., Maher, L., Palmateer, N., Taylor, N., Bruneau, J., & Hickman, M. (2017). Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, Article CD012021.

Stoicescu, C. (2012). The global state of harm reduction 2012: Towards an integrated response. Harm Reduction International.

Strike, C., Hopkins, S., Watson, T. M., Gohil, H., Leece, P., Young, S., Buxton, J., Challacombe, L., Demel, G., Heywood, D., Lampkin, H., Leonard, L., Lebounga Vouma, J., Lockie, L., Millson, P., Morissette, C., Nielsen, D., Petersen, D., Temis, D., & Zurba, N. (2013). Best practice recommendations for Canadian harm reduction programs that provide service to people who use drugs and are at risk for HIV, HCV, and other harms: Part 1. Working Group on Best Practice for Harm Reduction Programs in Canada.

Health Canada. (2020a). Supervised consumption sites explained. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/supervised-consumption-sites/explained.html

Health Canada. (2020b). Supervised consumption sites: Status of applications. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/supervised-consumption-sites/status-application.html

Wilson, D. P., Donald, B., Shattock, A. J., Wilson, D., & Fraser-Hurt, N. (2015). The cost-effectiveness of harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, S5–S11.

Working Group on Best Practice for Harm Reduction Programs in Canada. (2013). Best practice recommendations. https://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/best-practices-slides.pdf