Learning Objectives

By the end of this topic, the student should be able to:

- Explain the concept of cultural safety and its role in person-centred care.

- Explain the concepts of trauma-informed and trauma- and violence- informed practice and why they are important in the provision of services.

- Identify the key components of trauma-informed care (TIC) and trauma- and violence- informed care (TVIC).

Key Concepts

- Cultural safety is an overarching term to challenge and disrupt oppressive practices that marginalize and stigmatize groups of people; it is an anti-racist, anti-oppression stance.

- Trauma-informed care (TIC) is framed by five key principles: safety, trust, choice, collaboration, and empowerment.

- Trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) builds on the principles of TIC and is inextricably linked with cultural safety.

- TVIC includes four principles:

- Understand trauma and violence and their impacts on peoples’ lives and behaviours.

- Create emotionally and physically safe environments for both clients and service providers.

- Foster opportunities for choice, collaboration, and connection.

- Provide strengths-based and capacity-building approaches to support client coping and resilience.

- TVIC and cultural safety are key dimensions of equity-oriented approaches in health care, alongside harm reduction.

- Health and social service organizations and providers play a key role in ensuring equity-oriented health care that incorporates TVIC and culturally safe care. Developing a therapeutic relationship that minimizes power imbalances, promotes shared decision-making, and responds to institutional racism and social determinants of health inequities is an important aspect of TVIC and culturally safe care.

What Is Cultural Safety?

For more information, see Module 5, Topic E.

Cultural safety (CS) is an anti-racist, anti-oppressive, and anti-discriminatory stance. It can help reduce experiences of racism within health and social services while promoting better health outcomes.

Origins of CS

funkypancake/iStock

Cultural safety was conceptualized by Irihapeti Ramsden, a Māori nurse in New Zealand, in the late 1980s in response to the glaring health inequities between Māori (the Indigenous people of NZ) and non-Māori persons.

Similar to the situation in New Zealand, because of the impacts of colonialism, neocolonialism, and racism, Indigenous Peoples in Canada experience worse health outcomes compared to other Canadians on virtually every measure.

Nursing and Māori national organizations supported the theory of cultural safety, which upheld political ideas of self-determination and decolonization.

Definition

- Culturally Unsafe Space

- A space or practice is defined as “any actions that diminish, demean or disempower the cultural identity and well-being of an individual” (Nursing Council of New Zealand 2002, p. 9)

Terms related to but also different from cultural safety include:

- cultural competency,

- cultural awareness,

- cultural sensitivity,

- cultural humility, and

- cultural appropriateness.

Some authors have conceptualized cultural safety as part of an evolving continuum of terms. Although the notion of culture is central to the concept, cultural safety is not about conducting a cultural inventory. Rather, cultural safety (CS) is about relational engagement that is respectful, nonjudgmental, and authentic.

NOTE: CS is not about focusing on a person and on cultural difference as the source of an encounter or a problem; it is a focus on the culture of health care as a place where health providers can take action to create safety for all.

More Notes on The Value and Importance Of CS

- CS moves beyond cultural sensitivity or cultural awareness to place responsibility on health and social service providers to create culturally safe environments.

- CS foregrounds the aim of shaping health and social service practices, policies and organizations.

- CS takes into account the inherent power imbalance a health and social service provider and the person coming to them for care.

- CS begins with the self, that is, a provider’s reflection on their own biases and assumptions, and what they are bringing to the health and social service encounter.

Assessment and intake forms and even the physical layout can make people feel more or less welcome and respected. Providers need to think about what their waiting room looks like: is it a place where people feel welcomed? They can ask themselves what they have done to make people feel like this is a place where they can spend time safely.

Indigenous Cultural Safety

The harms of everyday racism in the health sector in relation to Indigenous people has been clearly documented. These events have brought renewed attention to the harms of Indigenous-specific racism.

- Events surrounding the tragic death on September 28, 2020 of Ms. Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old Atikamekw woman in Saint-Charles-Borromee, Quebec (Godin, 2020),

- the investigation into emergency department staff playing “games” to guess blood-alcohol levels of Indigenous clients (Schmunk, 2020), and

- the decades long investigation into the death of Mr. Brian Sinclair (Geary, 2017).

What Is Equity-Oriented Health Care?

For more information, see Module 5, Topic C.

Equity-oriented approaches can be implemented at multiple levels, including within health services, and have been shown, through prior and ongoing research in primary health care (i.e., Browne et al., 2015; Ford-Gilboe et al., 2018), to be related to key health outcomes, including better quality of life, less chronic pain, and fewer depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms over time.

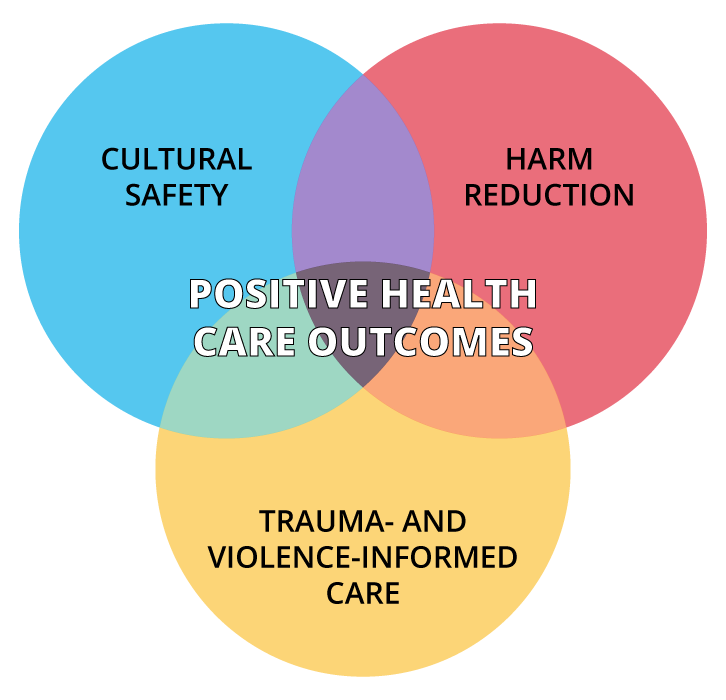

Equity-oriented approaches comprising three intersecting key dimensions—cultural safety, trauma- and violence-informed care, and harm reduction—have demonstrated positive outcomes.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

What Is A Trauma- And Violence-Informed Care That Includes Cultural Safety?

Definition

- Trauma-Informed Care (TIC)

- An approach underpinned by the recognition of the impacts of previous traumatic events on current health. However, the primary goal of care is not to directly address past trauma but to view presenting problems in the context of a client's traumatic experiences; TIC focuses on ensuring people are not re-traumatized in the delivery of care.

A trauma-informed approach works across individual, interpersonal, and system levels of care, and concentrates on:

- relationship building,

- engagement and choice,

- awareness,

- and skills building.

Definition

- Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care (TVIC)

- Builds on the principles of TIC, namely, safety, trust, choice, collaboration, and empowerment, by also focusing attention on and addressing the impact of everyday violence. Everyday violence intersects interpersonal (e.g., physical, emotional, sexual, and spiritual abuse) and systemic and structural violence (e.g., racism, homelessness, and political neglect), and its ongoing and cumulative impact.

The V in TVIC is a reminder of the fact that violence and its traumatic impact is ever-present in our society, occurs at the intersection of interpersonal and systemic or structural violence, and requires attention at individual, organization/agency, and system levels. It does not simply reside in an individual’s psychological state, and it is different from trauma incurred, for example, as a result of a natural disaster (Ponic et al., 2016).

Ken Duffney/iStock

An example of culturally safe and TVIC includes recognizing historical and contemporary impacts of colonial relations on Indigenous Peoples and communities. In response, altering the therapeutic environment and system of care to be informed by Indigenous knowledge and healing practices. This may include providing services to Indigenous people in their respective communities and providing treatment options that bring together Western and Indigenous knowledges, including Indigenous medicines, healing practices, land-based interventions, and the support of Elders, to name several.

Basic Principles of TIC

To be effective, the principles of TIC – safety, trust, collaboration and empowerment – need to occur at both the individual and structural level for effective and sustainable change.

Safety

Emotional safety can be promoted through:

- compassionate care,

- respectful language, and

- provider relationships that are consistent and predictable and where confidentiality is stressed and upheld.

Policies must:

- appropriately address health inequities within organizations and practice, and

- be well explained, clear, and make sense to the person to whom they pertain.

Physical safety can be promoted by:

- offering accessible spaces of care,

- providing adequate space that is bright with sufficient seating and a welcoming ambiance through people and furniture, and

- displaying art and signage that is welcoming of the people who access the services (this can also serve to promote emotional safety).

Trust

When a person’s basic needs for safety, respect, and acceptance in the helping relationship are understood and responded to accordingly, an atmosphere of trust can be established. Trust also is based upon predictability and transparency, such as taking the time to explain concepts such as confidentiality and allowing time for questions.

Choice

Trauma-informed services are person-centred and support client decision-making and a sense of control over their own recovery.

- Through time, people gain a new sense of control and mastery, holding the potential to transform feelings of powerlessness and being overwhelmed to that of a person with power who directs and owns their life decisions and associated outcomes.

- Encouraging mastery through choice involves asking people about their preferences in service delivery, supporting them to identify options suitable to their life experience, and guiding them in their own informed decision-making. For example, instead of shaming or labelling a person as resistant, service providers can work to understand the broader contextual factors contributing to a person’s refusal of help and support.

Collaboration

Trauma-informed programming is based on shared power between the worker and client so that the relationship offers a true alliance in healing; this requires recognizing the power imbalance and the presence of privilege in the helping relationship.

- Collaboration requires constant attention to the many subtle ways feelings of vulnerability can be reproduced.

- Individuals who have had abuse and violence in their past are particularly vulnerable to instinctive compliance and difficulties in placing their needs first, including asking questions or disagreeing.

Collaboration means understanding each person’s life history and cultural background and encouraging the person to be active in determining what interventions might be helpful. In this way, barriers to change are addressed and the helping relationship becomes a therapeutic tool.

Empowerment

Empowerment means adopting a strengths-based approach that reframes symptoms as adaptation and highlights achievements. Resilience instead of pathology is emphasized; for example, reframing trauma responses as normal reactions to threatening encounters.

Language plays a key role in empowerment as the individual is viewed as a survivor rather than a victim.

Watch this short video that describes how trauma informed care can make a difference (American Institutes for Research, 2014)

Used with permission from the American Institutes for Research.

Basic Principles of TVIC

TVIC includes four basic principles to be applied at both the service provider and organizational levels:

- Understand trauma and violence and their impacts on peoples' lives and behaviours.

- Create emotionally and physically safe environments for both clients and service providers.

- Foster opportunities for choice, collaboration, and connection.

- Provide strengths-based and capacity-building approaches to support client coping and resilience.

(Ponic et al., 2018; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018)

Four Ways a Provider Can Enact TVIC

- Build awareness and understanding.

- Emphasize safety and trust.

- Adapt language.

- Consider trauma a risk factor.

(EQUIP Health Care: https://equiphealthcare.ca/)

Tool to assist providers and organizations to enact TVIC

Please review the following:

For British Columbia: Trauma-and Violence-Informed Care (TVIC): A Tool for Health & Social Service Organizations (PDF).

For Ontario: Trauma-and Violence-Informed Care (TVIC): A Tool for Health & Social Service Organizations (PDF).

Questions

References

American Institutes for Research. (2014, October 22). What difference can trauma-informed care make? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd72Rx32EK4

Browne, A., Varcoe, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, N.C., Smye, V., Jackson, B., Wallace, B., Pauly, B., Herbert, C., Wong, S., & Blanchet-Garneau, A. (2018). Disruption as opportunity: Impacts of an organizational-level health equity intervention in primary care clinics. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17, 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0820-2 .

Browne, A. J., Varcoe, C., Lavoie, J. G., Smye, V. L., Wong, S. T., Krause, M., Tu, D., Godwin, O., Khan, K., & Fridkin, A. (2016). Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: Evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1707-9

Browne, A., Varcoe, C. M., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, N., & EQUIP Research Team. (2015). EQUIP Health Care: A multi-component intervention to enhance equity in primary health care settings. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(192). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0271-y

Browne, A., Gunn, B., LaRocque, E., Lavallee, B., Lavoie, J., McCallum, M. J. L., & Restoule, B. (2014). Racism in health system: Expert working group gets at factor sidelined at Sinclair inquest. Winnipeg Free Press. https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/opinion/analysis/racism-in-health-system-262987221.html

East, J., & Roll, S. J. (2015). Women, poverty, and trauma: An empowerment practice approach. Social Work, 60(4) 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swv030

Eby, D. K. (2018). Customer-ownership in equity-oriented health care. Milbank Quarterly, 96. https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/customer-ownership-in-equity-oriented-health-care/

EQUIP Health Care. (n.d.). Why focus on Indigenous people? https://equiphealthcare.ca/files/2019/12/WFoIP-Mar-23-2018.pdf

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, N., Varcoe, C. M., Herbert, C., Jackson, B., Lavoie, J., Pauly, B., Perrin, N., Smye, V., Wallace, B., Wong, S., Browne, A. J., & EQUIP Research Team. (2018). How equity-oriented health care impacts health: Key mechanisms and implications for primary care practice and policy. Milbank Quarterly, 96(4), 635–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12349

Geary, A/ (2017, September 18). Ignored to death: Brian Sinclair's death caused by racism, inquest inadequate, group says. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-brian-sinclair-report-1.4295996

Godin, M. (2020, October 9). She was racially abused by hospital staff as she lay dying. Now a Canadian Indigenous woman's death is forcing a reckoning on racism. Time. https://time.com/5898422/joyce-echaquan-indigenous-protests-canada/

Hamm, J. (2017, July 25). Understanding trauma: Learning brain vs survival [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KoqaUANGvpA

Levenson, J. (2017). Trauma-informed social work practice, Social Work, 62(2) 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx001

National Aboriginal Health Organization. (2006). Fact sheet: Cultural safety. https://www.saintelizabeth.com/getmedia/970b1d43-688c-4bb7-9732-09cc8d1d1716/Cultural-Safety-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2002). Guidelines for cultural safety, the treaty of Waitangi, and Maori health in nursing and midwifery education and practice. Wellington: Nursing Council of New Zealand.

Phillips, N., Adams, G., & Salter, P. (2015). Beyond adaptation: Decolonizing approaches to coping with oppression. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 365–387. https://jspp.psychopen.eu/article/view/310

Ponic, P., Varcoe, C., & Smutylo, T. (2016). Trauma- (and violence-) informed approaches to supporting victims of violence: Policy and practice considerations. Victims of Crime Research Digest (No. 9). Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rd9-rr9/p1.html

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2018). Trauma and violence-informed approaches to policy and practice. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/trauma-violence-informed-approaches-policy-practice.html

Schmunk, R. (2020, June 19). B.C. investigating allegations ER staff played “game” to guess blood-alcohol level of Indigenous patients. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/racism-in-bc-healthcare-health-minister-adrian-dix-1.5619245

Shelly, P. (2014, November 19). Your guide to trauma-informed care: Our latest infographic. SocialWorkSynergy. https://socialworksynergy.org/2014/11/19/your-guide-to-trauma-informed-care-our-latest-infographic/comment-page-1

Varcoe, C., & Browne, A. J. (2015). Culture and cultural safety: Beyond cultural inventories. In C. D. Gregory, L. Raymond-Seniuk, L. Patrick, & T. Stephen (Eds.), Fundamentals: Perspectives on the art and science of Canadian nursing (pp. 216–231). Lippincott.

Wyatt, R., Laderman, M., Botwinick, L., & Mate, K. (2016). Achieving health equity: A guide for health care organizations [White paper]. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Achieving-Health-Equity.aspx